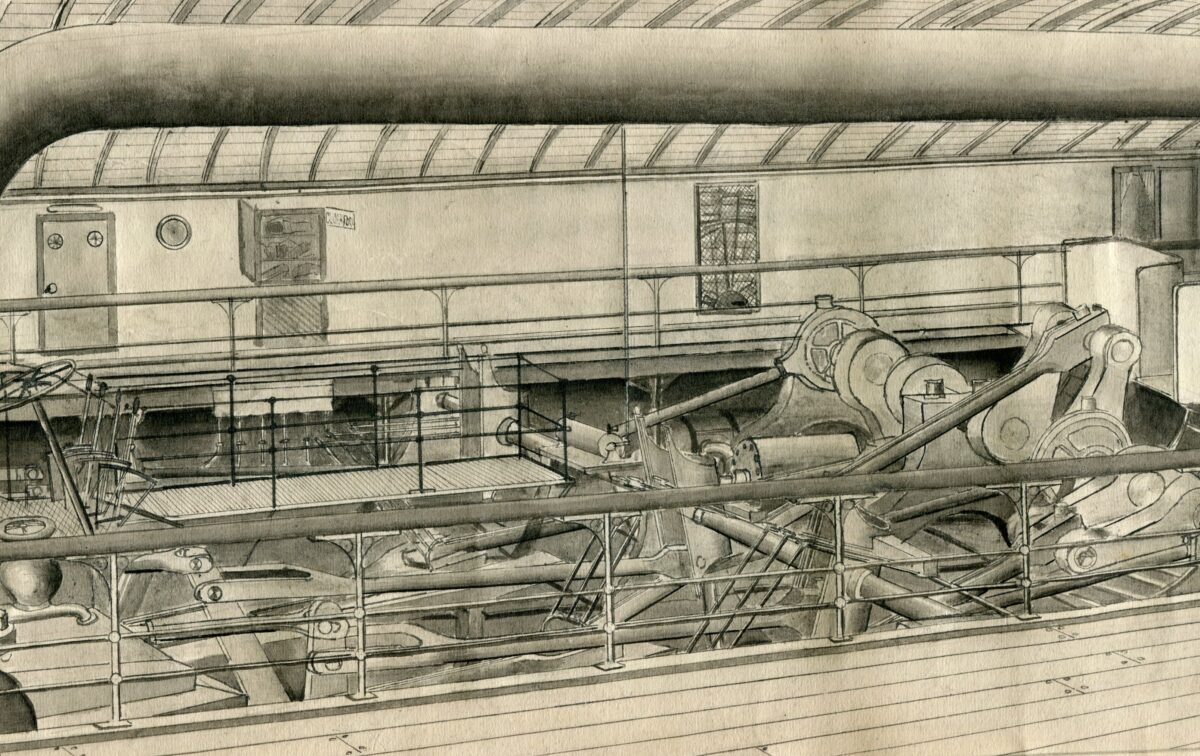

The late Stafford Ellerman’s Uncle Lewis Wood drew a number of pictures of ships of all sizes including a handful of the paddle steamers he had sailed on in his youth before the First World War. Amongst them is this fascinating drawing of the PS London Belle’s engine executed in 1905 when the ship was sailing on the London, Clacton and Walton service.

This 364nhp triple expansion engine was built by Denny and, as you can see, is fitted with their typical link gear for controlling the valve settings. On the far side you can see the opening into the port paddle box with a wire grille over it rather than a solid door. There are rails rather than solid bulwarks around the engine which was not uncommon at that time and which encouraged the free circulation of air between the engine room and the alleyways either side helping to keep the engineers cool. Along the top of the picture is the pipe bringing steam from the boiler to the high pressure cylinder.

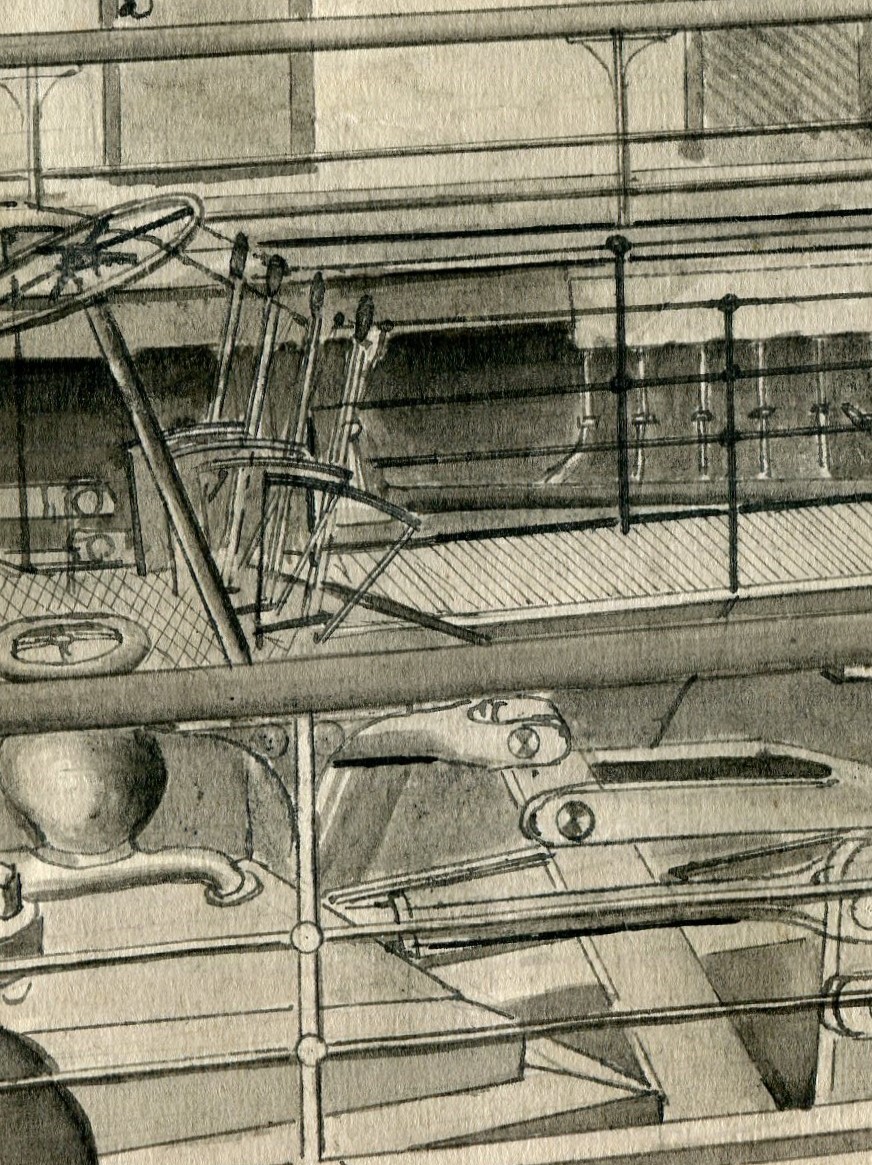

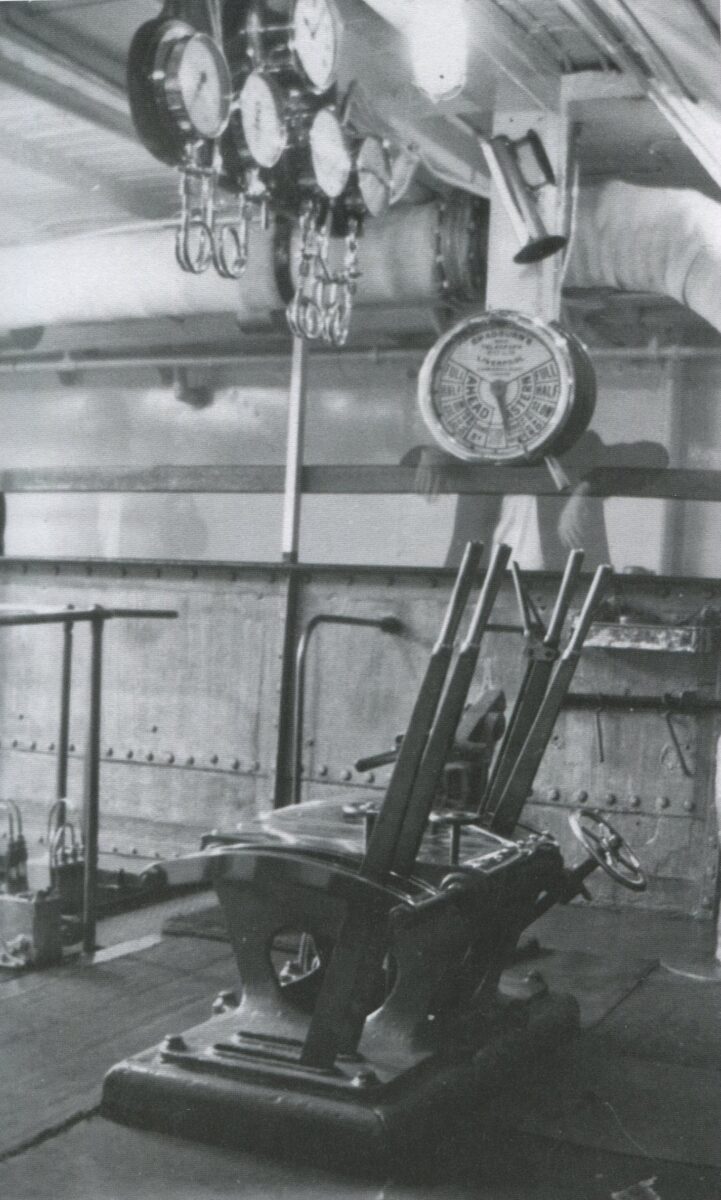

All such engines require the same controls: a main steam valve, a wheel or a lever to alter the valve settings ahead or astern and all points in between, an impulse valve to put steam into another cylinder if the high pressure side of the engine gets stuck on dead centre, and drains for however many cylinders the engine has. How they are arranged and what form they take varies between engines but they are all there in some form or another on all paddle steamer compound and triple expansion engines and all are positioned to hand for the engineer to use as necessary during manoeuvring.

This picture shows the three levers for London Belle’s three drains and a fourth for the impulse valve. There is a larger wheel for the ahead/astern valve settings and a smaller wheel below that for the main steam. On some paddle steamers the valves were controlled by a lever. On others, like on London Belle, a wheel. The advantage of the wheel (and that is what the Swiss paddle steamers have) is that it enables an infinite number of valve settings for ahead and astern. However the downside of the wheel is that it takes longer to go from full ahead to full astern with lots of turns necessary to achieve that instead of just pulling a lever across which is quicker. As you will know it is the valve settings which primarily control not only ahead and astern but also the speed of the engine. KC has a lever rather than a wheel for this and that gives her four valve settings for ahead and three for astern with the lowest, which we call number one, providing the most economical cruising speed and the highest, number four, the fastest and greediest for fuel consumption. On number one the engineer needs to put coal in KC’s boiler every now and again. On number four he is at it nearly all the time shovelling it in and therefore bumping up the fuel costs. And that is a matter of increasing concern today with the price of coal skyrocketing.

Coming into a pier when Stop is rung on the telegraph if the engineer just turns off the steam and puts the reversing gear into neutral the engine will continue to roll on ahead due to the forward motion of the ship through the water continuing to turn the paddle wheels. The trick is to put the engine into astern and give it sufficient steam to stop the engine in a position where the HP piston has a good length of stroke to get started for the next engine movement. Then when full astern is rung on the telegraph all the engineer has to do is open the steam valve and off the engine goes.

If the engine is not stopped in the right place, and particularly if it comes to rest at top dead centre with the HP piston at the end of its stroke, then the engine will be difficult to start and will need the use of the impulse valve which puts steam into another cylinder to get it going again. This scenario doesn’t happen very much with experienced engineers who know where to stop the engine in the right place to avoid it but it can happen. The worst case scenario is if the engine becomes not only stuck but also steam locked if, for example, the main steam and impulse valves are inadvertently opened at the same time by an engineer in a momentary fit of panic frantically trying to get a stuck engine started again.

It is to try to avoid this happening that the usual practice is to have the drains open during manoeuvring which helps to free up the engine and prevent steam becoming trapped in any one cylinder and locking the engine solid. This sometimes happened in the early days of running KC on the Medway before we got it sorted out. And I can tell you that there are few more worrying moments for a paddle steamer captain than finding that he has the telegraph set to full astern but finds nothing is happening below with the pier coming up fast. It was Harry Quirk, and Maurice Marryatt in that first season in 1985 who sorted this out for us and put the proper procedures in place to stop it happening again. To them I am forever grateful.

As I boy I watched Cyril Julien on Consul and Alf Pover, first on Monarch and then Embassy, handle the engines so from an early age I knew what they did and how they did it to make the engines dance. Consul’s impulse valve was a lever in line next to the drains and the reversing lever. On Embassy it was an L shaped horizontal lever within the nest of controls. Very occasionally I saw both Cyril and Alf use the impulse vale but I never saw them get the engine stuck. They were both masters of paddle steamer engine handling.

On my first trip as an eleven year old passenger on Princess Elizabeth in 1962 then running between Bournemouth and Swanage I noticed that the engineer didn’t stop the engine in the usual manner I had previously witnessed but allowed it to run on ahead when Capt Defrates rang Stop on the telegraph. Then when full astern was rung he couldn’t get it started astern and bang we landed heavily alongside Bournemouth Pier. It was on that day that I first heard a paddle steamer boiler safety valve lift. It is essential to damp down a boiler before arriving at a pier and this hadn’t been done so not all was well in the engine room that day I think. On my first trip as a passenger on Waverley in 1976 I noticed that there seemed to be issues in the engine room. Coming into one of the piers the chief forgot to put on the drains during manoeuvring and I looked on in amazement as the greaser knocked him out of the way and took over the engine controls himself. Things looked up the following year when Ken Blacklock was lured back to work on Waverley again. Like Cyril Julien and Alf Pover he knows how to handle a paddle steamer engine and make it dance.

Another aspect of paddle steamer engine handling is how fast the engineer responds to orders on the telegraph. This is not really very apparent to the overwhelming majority of onlookers. It did not occur to me until I started handling a paddle steamer myself. The telegraph rings. The engineer works the controls. But it is very obvious indeed to the captain who notices at once if he is getting a prompt or a slightly delayed response to the telegraph. In the early days of running KC I found that some engineers were much faster at delivering an engine response than others. It may only be a matter of a few seconds but that makes all the difference to precision paddle steamer handling.

Over all the many years I ran KC I came to feel that the two most important speeds which are absolutely essential for efficient paddle steamer handing are flat out and the deadest of dead slows. In the first case you often need that power to stop the ship exactly where you want it and also you need it to get the ship going again so that the wash from the paddle wheels gets back to the rudder to give you the ability to steer as fast as possible. Once you have steerage you can come back from full onto a slower speed. And alongside the pier for manoeuvring you need a really slow dead slow. Sometimes in the early days on KC I would ring slow and get something more approaching half putting far too much strain on the ropes. Sometimes the slowest of dead slows is not enough and you need more to help pull the ship alongside. But the starting point should always be the slowest of dead slows.

The real trick with all this is to train all the engineers to handle the engine in exactly the same way so that all the engine responses are always exactly the same whosever is on the controls. The Swiss are masters of it. Go on any paddle steamer anywhere in Switzerland and you will see the engineers ready for action and delivering very prompt engine responses to the telegraph or the voice pipe.

London Belle was built in 1893 for the London, Woolwich and Clacton-on-Sea Steamboat Company, otherwise known as the Belle Line, with a BOT Class II Passenger Certificate for their services connecting London, Clacton and Walton-on-the-Naze. The Class II was thought necessary for this service as the leg north of Clacton sometimes required the steamers to sail later in the evening than one hour after sunset, particularly if they were running late, which was one of the restrictions on the lesser Class III Passenger Certificate. It also allowed, if wanted, year round operation rather than just between April and October.

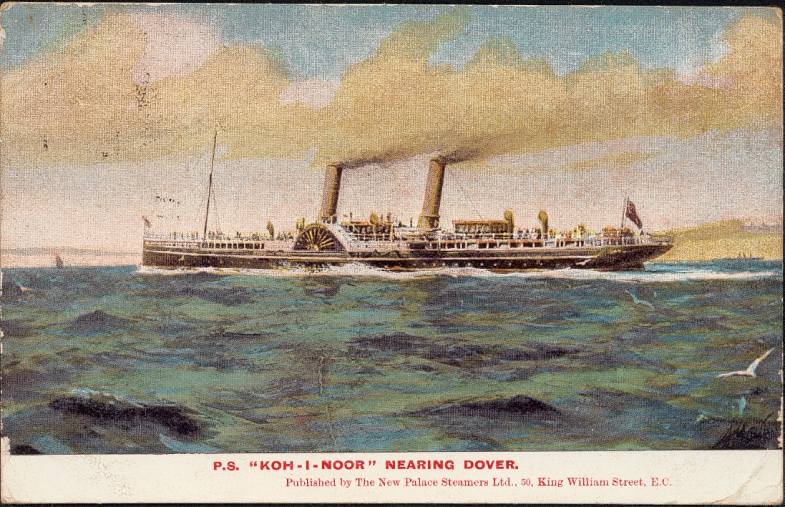

At a first glance all the Belle steamers have a great commonality of look about them and the casual observer might be forgiven for thinking that they were all the same size. But they were not. The smallest was the Woolwich Belle which was just 200ft LOA. The biggest was London Belle which was almost a third longer coming in at 280ft LOA. She was built at this larger size to counter competition from the rival Victoria Steam Boat Association’s 300ft LOA Koh-I-Nor which came out in 1892. Like Koh-I-Nor, London Belle was also a fast ship with a speed of 19.5 knots. That sort of speed was necessary for this service to try to keep to time when punching the sometimes fierce and adverse Thames tides which can knock a steamer’s speed over the ground back by as much as 4 knots.,

The route north of Clacton also brought its own issues for paddle steamers. At low tide there was not much water beneath the keel and the bottom on the leg northwards between Clacton and off Harwich. The paddle wheels churned up sand from the seabed. Sand is very abrasive and had a deleterious effect on the bearings in the feathering gear in the paddle wheels making them wear down at a disproportionately fast rate.

London Belle served in the First World War as a minesweeper and participated in an expedition to Archangel in North Russia as a hospital ship. When returned after war service she was 27 years old and approaching the end of her design life. She was sold to the P.S.M. Syndicate who do not appear to have used her. In 1925 she was bought by the Royal Sovereign Steamship Company and put on their services, alongside Royal Sovereign running from London to Margate until 1928. This was her last season in service after which she was sold for scrap to T W Ward at Grays in Essex in March 1929.

1928/29 was a seminal year for the London fleets with both the East Anglia Steamship Company, with its remaining Belle fleet, and the Royal Sovereign steamers going out of business. Some found other work for a time and Royal Sovereign survived for one season more in 1929 in the ownership of the General Steam Navigation Co. 1929 also saw the opening of the new Tower Pier and the closure of Old Swan Pier thereby doing away with the need for any of the steamers to have telescopic funnels to get under London Bridge.

In Conclusion: Like London Belle ships are built for a design life of 25 to 30 or so years. This envelope can be pushed with careful maintenance but if you want to keep them operational for much longer than that then you will need to spend money on them rebuilding and refurbishing them along the way. That was ever the case with paddle steamers from the past which had disproportionately long careers. It remains the case today. The Swiss routinely rebuild all their paddle steamers every 30 or so years. They take them back to nothing and build them up again with steelwork renewals as necessary, new decks and much else.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran