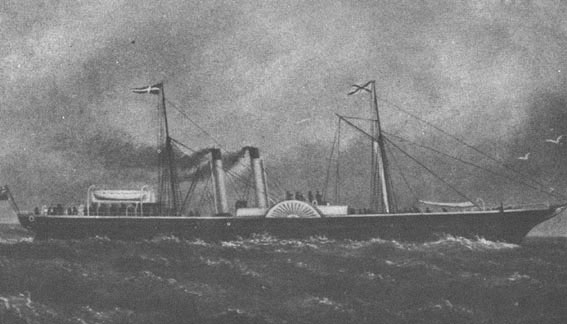

The paddle steamer Cygnus (pictured above) and her sister Aquila were built of iron on the Clyde in 1854 for the North of Europe Steam Navigation Company’s link between Harwich and Antwerp, a service which lasted for only a few months. After a charter on the same route the following year to the Eastern Counties Railway these fine new vessels were then laid up until taken over in 1857, first on charter and subsequently bought, by a new organisation, the Weymouth and Channel Islands Steam Packet Company, which planned to take advantage of the railway’s recent arrival in Weymouth and provide an onward connection to Guernsey and Jersey. The practically new vessels were ideally suited for the route, gained much favourable press comment when the service started in April 1857 and were destined to provide the main connection between Weymouth and the Channel Islands for the next thirty years.

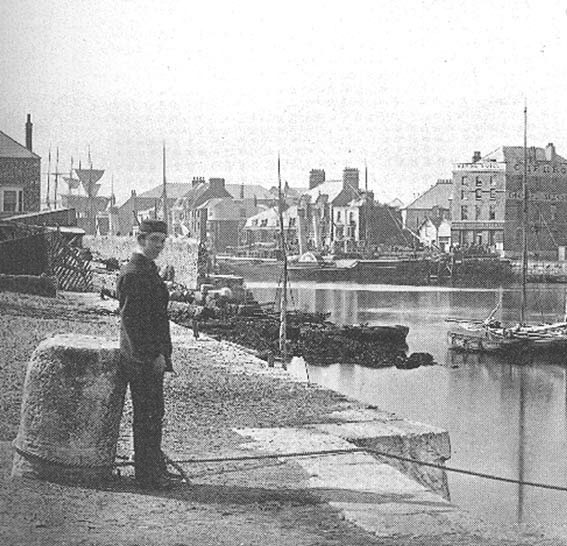

Here is the Aquila in the background alongside at Weymouth on a sunny and calm day in the late 1870s with a young man, at the outset of his career, looking on. We know what subsequently happened to the Aquila, as you will see later on, but we don’t know what happened to this young man. Did he have a happy life? Did he go to sea? Did he live to a great age or die young?

I suppose that he is about eighteen in this picture which would make him born in, say, 1860. Like many young men of the time he might have gone off to fight in, or be killed in, the Boer Wars of 1880/81 and 1899/1902 in South Africa. If he had survived or avoided that and lived into his fifties then he might well have seen his own sons, if he had any, go off to be part of the ten million combatants killed or gassed in the dreadful carnage of the First World War. He would have been of retirement age around 1925 just as the great economic depression was about to set in and, if he had got to eighty five, would have seen the USA drop on Japan the first ever atomic bomb, a scale of deadly weaponry beyond the dreams of Admirals and Generals when he was a boy.

Or, if he had been really lucky and lived to be a hundred then, like his pretty much exact contemporary Mr Frederick Reading of Preston, Weymouth, born 1859, (pictured above right) he might have been welcomed aboard the paddle steamer Consul by Capt Harry Defrates for a celebratory one hundredth birthday treat from Weymouth to Bournemouth in the summer of 1959. Like Mr Reading’s, the young man’s life would then have spanned pretty much the entire history of UK excursion paddle steamers from their development in the 1870s, expansion in the run up to the First World War, consolidation in the inter war years and decline and fall in the 1950s and on into the 1960s. What a life he would have had. How many paddle steamers he might have sailed on. How much change he would have seen.

But let’s get back to the Channel Islands route and what could be nicer than a fresh morning in St Helier Harbour, Jersey watching the arrival of the Great Western Railway’s Gazelle. Imagine that you are standing on the harbour breakwater with the camera in your hands. The flags and the wavelets show that the wind is from the north west so it will be feeling a little bit cool. From the shadows on the ship the sun is in the east behind you so it is rising and therefore this is early morning. Take a deep breath. You can almost smell the salt in the fresh Atlantic blown sea air as the Gazelle glides into the harbour entrance which is just out of shot on our right.

The Great Western Railway had had a financial interest in the Weymouth and Channel Islands Steam Packet Company but, as the Cygnus and Aquila were coming to the end of their economic life towards the close of the 1880s, they decided that they would build three new ships themselves and take over the route completely. It was their railway bringing their passengers to Weymouth so why shouldn’t it be their boats, entirely under their control, which took them onwards? The Lynx, Antelope and Gazelle of 1889 were the result and the Cygnus and Aquila were put up for sale. Propeller rather than paddle driven, larger, more commodious and altogether more up to date than their paddle predecessors the new ships retained a little bit of the old design with their arrangement of two small diameter and well raked funnels set close together.

They turned out to be a great success and, within in a year, the ratio of passengers travelling from Southampton with the London and South Western Railway and from Weymouth with the Great Western Railway to the Channel Islands switched from 3:1 in favour of Southampton to equal shares from both the ports. Larger and enhanced versions of the new ships were added to the GWR fleet with the Ibex of 1891 and the Roebuck and Reindeer of 1897, the latter two having a reputation for guzzling coal so seeing service mostly only during the summers. They all set the scene which continued right through to 1925 when the next generation of Weymouth to Channel Islands passenger ferries, St Helier and St Julien, were built.

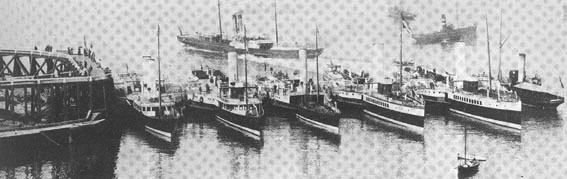

That might have been the end of both the Aquila and Cygnus but, no, they found further gainful employment for a time in their retirement. The Aquila was first sold for service in the West Country where she ran both local excursions and cross Channel trips to France and the Channel Islands until 1894 when she was sold again. In 1895 she was offering trips on the Bristol Channel including at least one to Lundy Island from Ilfracombe where she can be seen backing out from the pier in the above paddle steamer laden picture looking most antique compared with the array of modern excursion steamers in the foreground which were (left to right) Ravenswood, Lorna Doone, Bonnie Doone, Cambria, Westward Ho! and Earl of Dunraven. 1896 saw her running on the Sussex coast including to France now under the name Ruby but that did not last long and, after passing through the hands of several more owners who didn’t do much with her, she was finally scrapped in 1899.

The Cygnus passed first to a Mr Holden who planned to run her between Preston and Douglas on the Isle of Man and then on to David Macbrayne in 1891. After a thorough rebuild, with new paddle boxes and only one funnel, she emerged as the Brigadier and sailed on various routes in the Western Isles before hitting a rock off the Isle of Harris on 7th December 1896 where she sank and where she still remains in deep water today. Fortunately all the passengers and crew were saved.

So that’s the Aquila (pictured above) and the Cygnus. Built, operated for more than thirty years on the Weymouth Channel Islands route, a subsequent twilight career for both, then eventually scrapped or sunk. That’s their lives. Finished. Gone. No more. But what about the tsunami I hear you say. This piece is headed “Paddle Steamer Hit By Tsunami in English Channel” Where is this tsunami then?

Well, like saving up the tastiest morsels on the Christmas platter to savour last of all, I have kept back this nugget of interest to the end. Whilst researching his excellent book “Weymouth to the Channel Islands – A Great Western Railway Shipping History” (if you don’t have a copy buy one – it’s tip top and only £13.95 from the Oakwood Press) railway and maritime historian Brian (B L) Jackson found an absolutely fascinating account in the “Southern Times” of the Aquila hitting “A Tidal Wave in the English Channel – a very curious and dangerous phenomenon” in the early hours of Saturday 31st March 1883 whilst on her regular overnight passage from Weymouth to the Channel Islands.

The paper goes on:

The weather was calm and the sea smooth, when an hour out with the Shambles light still in sight, the steamer was struck violently by successive mountainous seas which swept her decks from stem to stern. Water flooded the saloon, ladies’ cabin, fore cabin and engine room, having smashed the glass of various skylights, and one of the paddle boxes was damaged, a rail on the bridge twisted, and various items of cargo shifted, were damaged or swept overboard. Owing to the pump being damaged the cabins had to be baled out with buckets and the skylights were covered with tarpaulins before the vessel proceeded on its way. It was recorded that five minutes after the waves had struck the steamer the sea became perfectly calm.

The report does not call this “tidal wave” a tsunami but it does sound rather like one to me. A calm night with mountainous seas coming from nowhere and then flat calm again. That’s just what tsunamis and their cousins meteotsunamis do. And remember that 1883 was a year of tremendous volcanic activity around the world with Krakatoa going off big time that summer causing tsunamis in the Indian Ocean with waves said to be 30m high and with the effects of the eruption going around the globe. Thirty five thousand were killed as a result. That’s right. Thirty five thousand! So the tectonic plates were on the move that year.

Nor is the Aquila’s scary encounter the only example of tsunami style waves hitting our coast. Digging down one finds more episodes including giant waves in the Dover Straight near Calais which killed hundreds on 6th April 1580 following an earthquake in the seabed; the massive Bristol Channel flood of 30th January 1607, which was originally put down to a severe storm surge but is now thought more likely to have been a tsunami, in which more than two thousand lost their lives; a 3m tsunami which hit the Cornish Coast on 1st November 1755 following an earthquake in Lisbon; another in the North Sea on 5th June 1858 during which a witness saw the sea at Pegwell Bay retreat 200m and then come back in again within twenty minutes; another along the South Coast on 20th July 1929 with a wave height variously reported as being between 3.5m and 6m high sweeping up onto the beach at Brighton; and as recently as 29th June 2011 a mini tsunami along the Devon Coast, said by some to have been caused by an underwater landslide 200 miles out to sea, with the tide suddenly going out and coming back in again followed by a small surge which was videoed sweeping up the River Yealm.

And whether these were all tsunamis caused by seabed movements or meteotsunamis with their atmospherically generated waves of large amplitude, the result is exactly the same: potentially big and unexpected waves of massive force not produced by the wind. Not good news.

Fortunately none of these events were on quite the same devastating scale as the worst tsunamis elsewhere in the world, although the Dover and particularly the Bristol Channel ones were bad enough. And, on a positive note, despite her battering, the Aquila did survive her encounter with mountainous waves to paddle on for another fifteen years which is glowing testament not only to her crew that night but also to her design and construction, a design and construction which would be unlikely to gain approval from the regulatory authorities for Cross Channel work today.

But for me, having hitherto lived my life under the comforting illusion that tsunamis are things which happen to other people in other parts of the world and that the likelihood of one of them storming up the English Channel past the Shambles Bank off Portland Bill in the early hours of the dead of a dark night is about equal to the possibility of finding a Chihuahua dog landing a Lufthansa jet in Bremen, then the Aquila’s little adventure has brought me up sharp and made me think again. And I am beginning to wonder if moving home to the mountains of Switzerland might not be such a bad idea after all!

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran