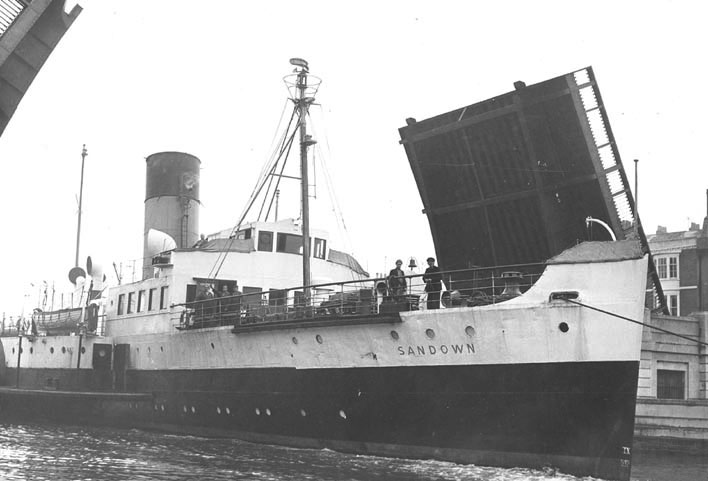

Fifty years ago in the “Deep Freeze” winter of 1962/63, Cosens & Co of Weymouth boosted their refit work by securing contracts to do major overhauls on two paddle steamers alien to the port. The first to arrive was the British Railways’s Portsmouth to Ryde ferry Sandown, pictured here passing through the Town Bridge on 15th October 1962, on her way to berth outside Cosens’s workshops in the Backwater.

A month later, with work completed, she moved out and P & A Campbell’s Bristol Channel paddle steamer Bristol Queen moved in. Here she is, in a wonderfully atmospheric picture taken by one of the founder members of the PSPS, Bernard Cox, on 13th November 1962, sandwiched between the Sandown waiting to leave for Newhaven and Consul having just completed her last season for Cosens and laid up outside Haymans for the winter.

With the Embassy already in the Backwater that makes four paddle steamers in the Harbour all on one day. What a delight. And by rights it should actually have been five! The Princess Elizabeth regularly wintered at Weymouth from 1961 to 1968 but 1962 was the exception. After a dreadful season running from Bournemouth she saved the cost of steaming home along the Dorset Coast and laid up on a cheap buoy in Poole Harbour, just off Hamworthy, instead. So four it was.

The local press was in effulgent form with headlines billing the Sandown as a “Giant”, which I suppose she was compared with the Consul, and the Bristol Queen as “Queen’ of England’s paddle steamers” a title which pleased the English whilst allowing those north of the border to continue their dreams of a higher status for their own Clyde flyers.

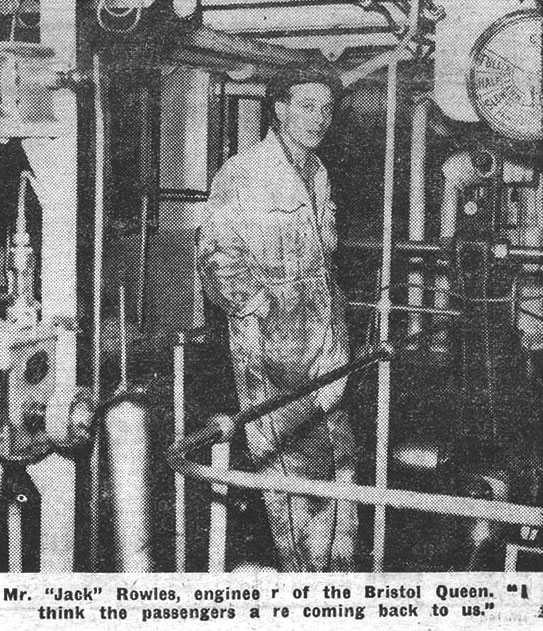

A journalist came aboard and interviewed Bristol Queen’s Chief Engineer Jack Rowles. “It is one of those 24 hour day jobs for the boats don’t rest while the summer season is on.” he said. “And it can be a bad weather job too with the boat rolling beam on on the swell coming up Channel and no other way to go about it because she has to cross with the paddles straining as they dip into the swell. It can be a tricky job too – witness the slight damage to the housing over the port paddle. The tide can be difficult in the Channel and at some piers a man with white-painted flaps has to guide the captain in the direction of the current. We bumped because at the last moment the tide changed. It turned in a manner of minutes. And the storms can come up quick. You can get 10ft, 15ft waves.”

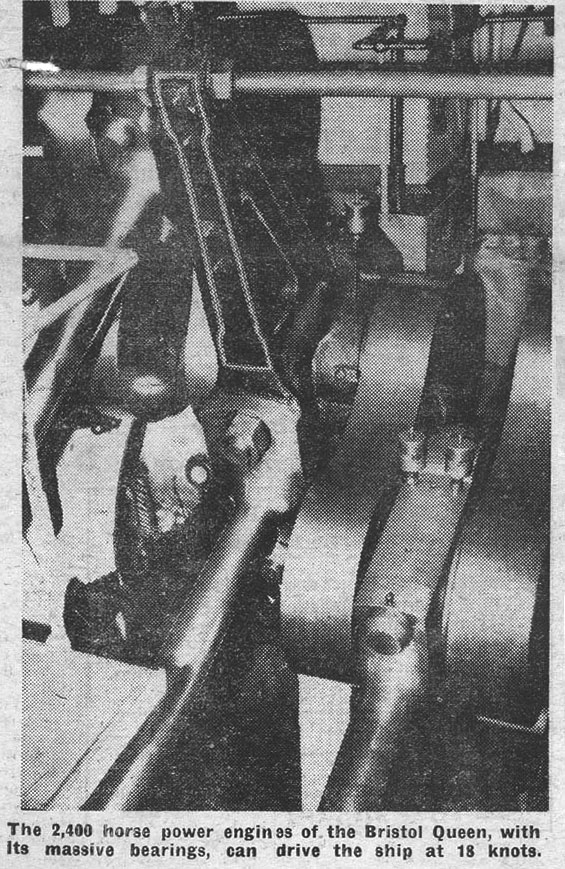

Works Manager Mr Herbert Gill, who spent a lifetime with Cosens, was also probed. “This is a different age today.” he said. “Nobody is satisfied to go slowly along the coast looking at the countryside and the coastline. They want to get on quickly. This is a fast age.” He then took the reporter on a tour of Cosens’s offices with their varnished deal planked walls and glass-cased paddle steamer models. “The wood has been varnished every five years since it was put in place seventy years ago” he said. “It’s Dickensian. I’d like to see it done in a nice pastel shade, like we painted the office downstairs. It’s no recommendation today to be Dickensian. Why do we carry on? Well, like so many things Victorian, the paddler has its advantages. No other boats so big and so powerful can get into such shallow water.

“It’s handy for getting on and off piers” said Mr Rowles.

“One of ours runs up onto the beach” added Mr Gill (the Consul)

Optimistically Mr Rowles replied “Personally I think that they are getting popular again. We seem to be carrying more people these days.”

A little wistfully, Mr Gill said “It’s rather like a man with an old car. He can’t afford to sell it; he can’t afford to run it; he just has to keep using it for the pleasure it gives him.”

The Bristol Queen’s overhaul was originally scheduled to be completed in January but it did not turn out like that. December was a cold and foggy month with fitful snow falls here and there. A huge anticyclone then set itself up over Scandinavia driving Artic wind southwards and, by the end of the month, the UK, including Weymouth, a town not much generally snowed upon, was covered in deep drifts in some places as high as twenty feet. In the ensuing transport chaos, British Railways managed to misplace a goods wagon containing the new set of boiler tubes destined for the Bristol Queen at Weymouth.

For all worried that our weather is getting more extreme than ever these days, it is re-assuring to remember 1962/63. It was cold, that winter. Very cold. There was snow that winter. And lots of it. It was so bad that the Thames froze a mile out to sea at Herne Bay and many rivers, including the Medway and Humber, froze over. And it went on week after week after perishing week chilling the interiors of the nation’s houses, houses which had never had the benefit of the sort of insulation to keep the cold out which is normal in more often snowed upon lands.

It was almost the coldest winter on record with only 1683/84 significantly colder and only 1739/40 marginally so. We have never seen a winter like it since. Even those cold ones in the last couple of years came nowhere near it.

With the anticyclone seeming to have rooted itself permanently in the best possible position to send arctic winds our way, more snow fell in February and it was not until early March that the thaw eventually set in, an event greeted by much national rejoicing up and down the land as temperatures soared to 17C and hats, gloves and snow boots were abandoned for the first time in months.

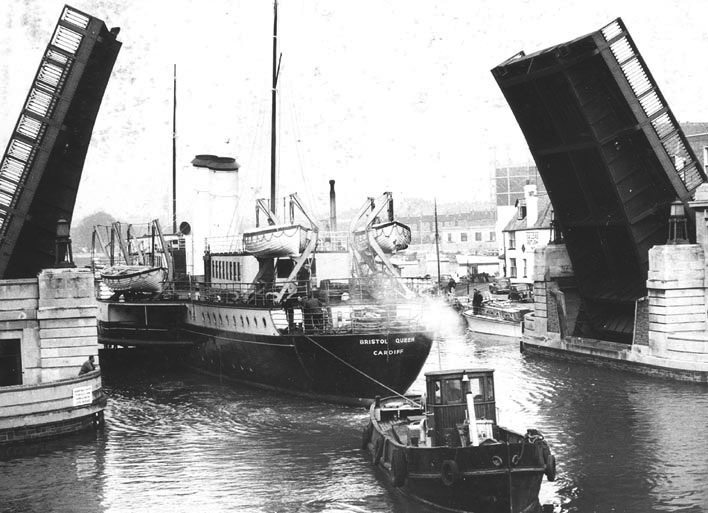

The missing boiler tubes were eventually located, directed correctly and installed. The rest of the refit work, which included fitting new inner funnels, was finished. And Bristol Queen finally sailed out through the Town Bridge at Weymouth outward bound for the Bristol Channel on 25th April, (pictured above) three months late.

It had been a difficult winter but it had all worked out well in the end.

So well, in fact, that there were hopes that two “foreign” paddle steamers visiting Weymouth for overhaul that year might bode well for the future. Perhaps next year there might be three? Perhaps the Ryde or the Cardiff Queen or, wonder of wonders, what about a giant from the Clyde? Maybe the Jeanie Deans?

But no. Such joy was not to be. No more new paddlers came. And the Sandown and the Bristol Queen turned out to be the last paddle steamers from “foreign parts” to come to Weymouth for a refit by Cosens.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran