On Sunday 2nd June 1940 Freshwater left Sheerness at 12 noon for Dunkirk under the command of Lt Church RN (Retired).

The previous Sunday 26th May 1940 marked the start of Operation Dynamo to evacuate over 300,000 allied troops from the harbour and beaches around Dunkirk retreating from the advancing German army. It is estimated that over a thousand ships and boats of all shapes and sizes took part in the operation, of which twenty-seven were paddle steamers. All came under heavy fire from the Germans, including bombardment from the air by the Luftwaffe. At least 200 were sunk including six paddle steamers, Brighton Belle, Brighton Queen, Crested Eagle, Devonia, Gracie Fields and Waverley.

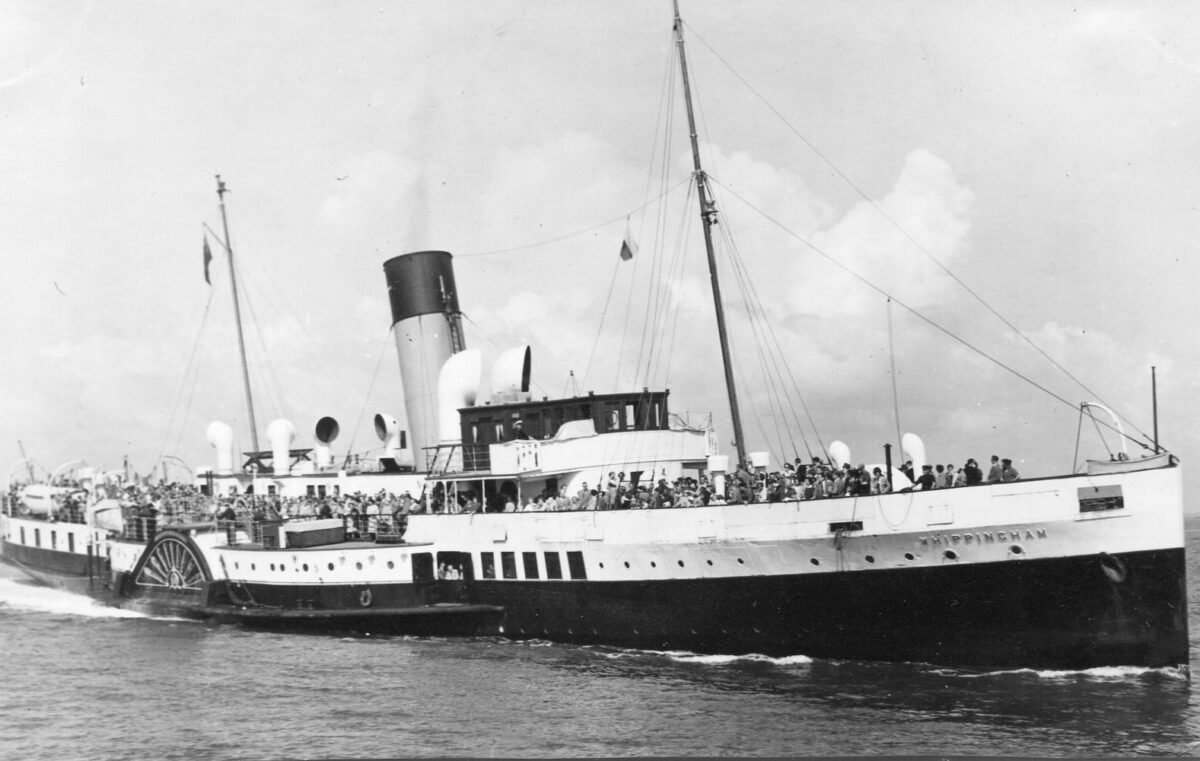

The evacuation started in earnest during the night of 26/27 May and proceeded amidst chaotic conditions in the ensuing days. As the week wore on the Admiralty desperately cast around for more shallow draft ships to bring in to help before the Germans reached Dunkirk, and to cover the losses, so in the small hours of May 30th called up with immediate effect the Southern Railway’s paddle steamers Freshwater, Portsdown and Whipingham which at that time were all still running on the Isle of Wight ferry services.

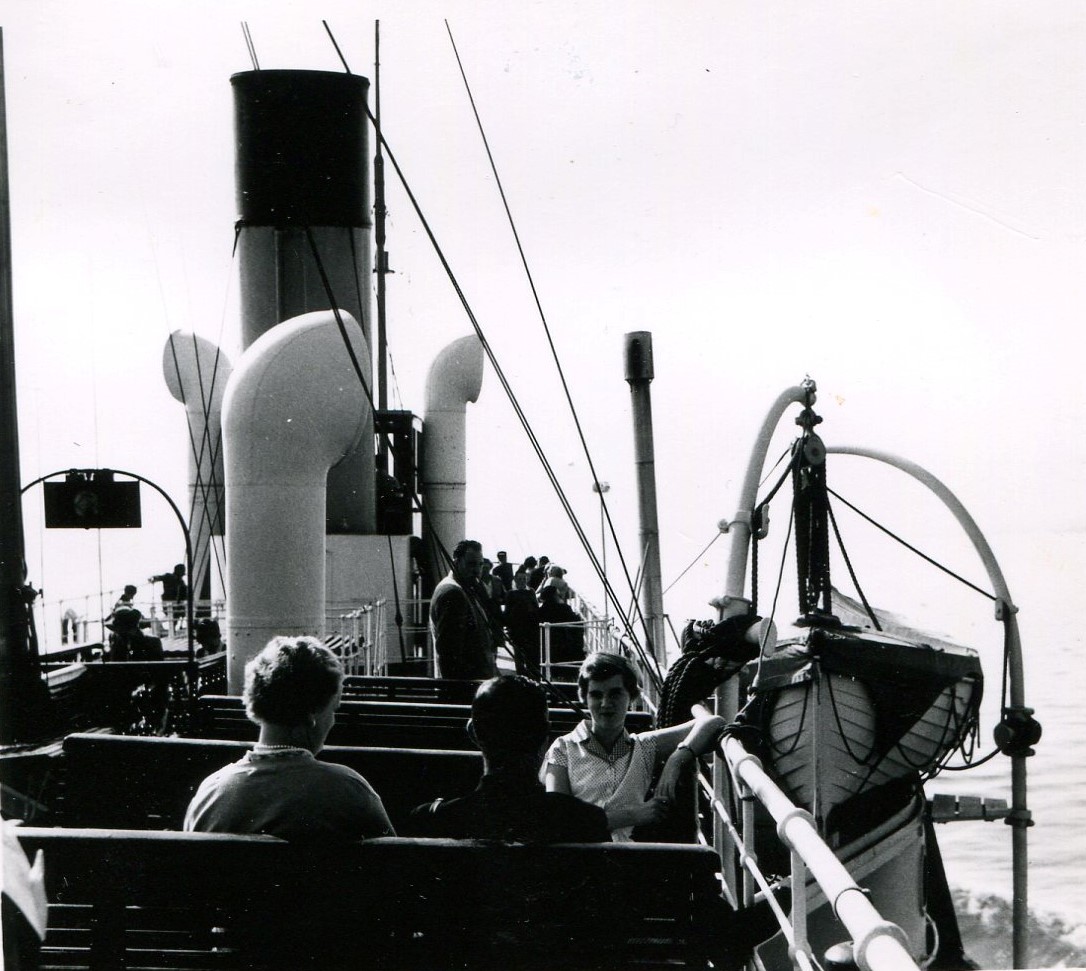

Whippingham and Portsdown, with new naval crews aboard, left Portsmouth in the early hours of the Friday morning for the Dover Straits. Whippingham arrived at Ramsgate at 12 noon where she needed to top up her boiler water reserve tanks. With the harbour bursting beyond capacity she could not access a hydrant so with the pressing nature and urgency of her mission she filled them up with sea water instead and set off at 1.45pm under the command of Lt E Fleet RNR anchoring off Dunkirk at 6.30pm to await orders. At 9.30pm she was instructed to weigh anchor and go in alongside the mole to pick up troops during which she was strafed by shell fire. Having loaded 2,700, more than twice her normal passenger capacity, she left at 1.30am on the Saturday morning and was off Ramsgate by 8am. However the harbour was full so she was ordered on to Margate where the troops disembarked at 11.30am. After that she was ordered to coal up and give the crew some much needed sleep.

Freshwater was not as fast as Whippingham and so took longer to get there as well as needing to refuel before crossing to Dunkirk so was ordered to sail on to Sheerness first to take on coal. This delay meant that it was not until the morning of Sunday 2nd June that she set off at 12 noon from Sheerness for the voyage down the Kent coast and across the Channel with a view to arriving off Dunkirk soon after dark.

As they had just come off the ferry run none of these three paddlers were fitted with any sort of military kit, guns or other armaments to help protect themselves which inevitably was a worry. Moran Caplat, mate of Freshwater, records in his excellent autobiography Dinghies to Divas published by Collins in 1985: “We were defenceless against attack, but I thought that perhaps we could deter the enemy if we appeared to have machine guns on the upper deck. With the help of some of the deck hands, a few broom handles, bits of canvas and the craft of improvisation that several years in the theatre had taught me, we rigged up a number of not very convincing dummy guns at strategic places on the bridge and upper deck, with instructions that if enemy air attack appeared to be imminent, they were to be manned and threateningly manoeuvred.

Under cover of darkness Freshwater put her bow up towards the beach to the east of Dunkirk Harbour to collect troops and was at first astonished to find nobody there. Mate Moran Caplat was sent ashore in one of the boats. He managed to locate some army officers and they organised a large and disorganised array of desperate troops all desperate to get aboard and all desperate to get away pronto.

On the return journey Freshwater went to the assistance of a deeper draft trawler which had run aground expecting to take off her crew and maybe a few refugees. Instead, what Moran Caplpat described as “the better part of the French army” came out of nowhere and swarmed aboard. There was no room for them below so they filled up the entirety of the promenade deck. And so Freshwater returned to Ramsgate on the Monday morning with her paddles deeper in the water than they were ever designed to be.

In the early afternoon she was ordered to sail for Sheerness to take on more coal with a view to making another run across but by the time that she was ready to sail once again the last ship had left Dunkirk and the evacuation was over with the Germans hoisting their swastika in Dunkirk on Tuesday 4th June.

Like Freshwater, Portsdown first sailed to Sheerness to take on coal where she arrived on Saturday 1st June before setting off for Dunkirk. She made one round trip returning more than 600 men to Ramsgate.

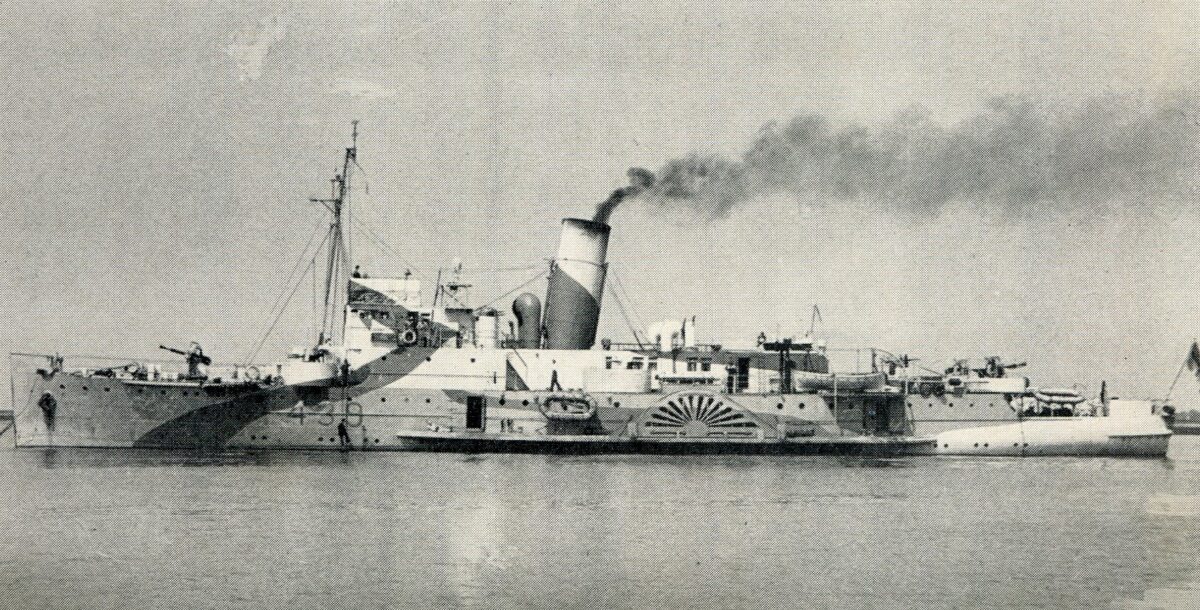

There was one other Southern Railway Isle of Wight ferry, Sandown, which took part in the evacuation. She had been taken over by the Admiralty in September 1939 and by May 1940 was based at Dover as a minesweeper so was well placed to be in the forefront of the rescue mission. She made her first trip across on the evening of Monday 27th May in company with Gracie Fields, Medway Queen, Princess Elizabeth and Brighton Belle and made at least two more round trips.

There was a lot of toing and froing of senior and other personnel during this chaotic week with the Admiralty trying hard to source and combine the best of practical experience and wisdom with the best of youthful energy to try to get optimum results on these nightmare missions into the gates of hell. This is how Moran Caplet unexpectedly found himself moved from his command of a flotilla of small boats at Sheerness to become Freshwater’s mate at a moment’s notice. He described his new captain, Lt Church, as “twenty-odd years my senior, long out of the Navy, a worried family man, unhappy at having to go on such a dangerous mission in the first place, worried at the responsibility of command, but brave and kind.”

Cdr Greig RN (retired) was another former naval officer brought out of retirement to help the war effort. He was captain of Sandown for her first crossings to Dunkirk with one report saying that he later was transferred to bring his experience to Portsdown. To keep his spirits up Cdr Grieg brought his dog Bella with him which the crewtook up as their mascot christening her “Bombproof Bella” as although the ships Cdr Greig commanded were bombed repeatedly no serious damage was ever caused. Well done Bella. Woof woof.

None of these paddle steamers ever had Board of Trade Cross Channel Passenger Certificates for their peace-time activities. Indeed Freshwater and Portsdown ran on only Class IV PCs for “Partially Smooth Waters”, as defined by the Board of Trade, within the Solent. But with true “Dunkirk Spirit” they saved very many more grateful troops than would ever have been permitted aboard on any of their peacetime trips on the UK’s Categorised Waters.

After their Dunkirk adventures, Freshwater, Portsdown and Whippingham then returned to the Solent to resume their Isle of Wight ferry duties. Whippingham was called up the following year for use as a minesweeper. And Portsdown hit a mine and sank off Spithead on the morning of 20th September 1941. It is a curious twist of fate for a paddle steamer to have gone through and survived all the horrors of Dunkirk largely unscathed and then to be have ended up being sunk by a German mine whilst on her regular passage between Portsmouth and Ryde. But as was often said during the war: if a bomb has your name on it there is nothing you can do about it. And if it hasn’t then why worry. That showed a heady optimism which helped to carry many people through the dark days or war.

Unexpected Facts 1: Feshwater’s mate, Moran Caplat, started his career as an apprentice for the General Steam Navigation Company and worked briefly aboard the Golden Eagle but found that it wasn’t for him so left and went to RADA to train as an actor instead. An experienced amateur yachtsman he joined the RNVR during the war which is how he appeared on Freshwater. After the war he became the General Administrator of Glyndebourne Festival Opera from 1949 to 1981.

Unexpected Facts 2: Whilst all the other paddle steamers which put in a appearance at Dunkirk were already called up for service in the Royal Navy and hence were painted battleship grey, Freshwater, Portsdown and Whippingham flew the white ensign for these few days whilst still painted in their peace-time civilian livery including buff funnels with black tops.

For more details of Freshwater’s trip to Dunkirk click here.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran

This article was first published on 2nd June 2021.