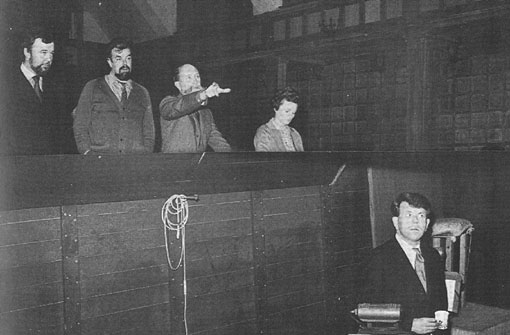

A question: What have Herne Bay, Sheerness, Dunkirk, Glyndebourne Festival Opera and the paddle steamers Golden Eagle and Freshwater, all got in common? The answer: Moran Caplat, pictured above pointing towards the stage at Glyndebourne with, from left to right, the distinguished stage and opera director Peter Hall, the designer John Cox, production manager June Dandridge and, in the orchestra pit below, the conductor, a youthful Raymond Leppard.

Moran Caplat grew up in Herne Bay and loved the water, often sailing along the Kent coast and up the Medway in his youth aboard his little dinghy. After leaving school he was briefly apprenticed as an engineer to the General Steam Navigation Company at their Deptford yard. He recalled “I was taunted and deliberately aroused, as were others of the younger members of the workforce, by the gangs of fearsome female cleaners of all ages who swarmed over the Thames Estuary pleasure steamers which were in the yard for their winter refit. Finally, while working by candlelight on the plumbing in the cold and echoing ladies’ lavatory of the paddle steamer Golden Eagle (pictured above at Ramsgate) I was laid low by bronchial flu. I wheezed in my digs in a state of great despondency until my father came to rescue me, took me home and succeeded in getting my apprenticeship to the General Steam Navigation Company annulled.” When recovered, Moran applied to RADA and set off for London and a career on the stage.

This ambition was put on hold with the outbreak of the Second World War in which, like many peacetime yachtsmen, Moran (pictured above left) was commissioned in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. It was as a sub-lieutenant in the Wavy Navy, so called on account of its distinctive gold braid, that he became mate of the Southern Railway paddle steamer Freshwater for one round trip to Dunkirk.

Well over a thousand vessels from cargo ships through cross channel ferries down to small private yachts took part in the evacuation of nearly three hundred and forty thousand troops, all in the disarray of retreat, from Dunkirk in the week from Monday 27th May to Tuesday 4th June 1940. Between twenty five and twenty seven of these vessels were paddle steamers, according to which record you look at, of which six, Brighton Belle, Brighton Queen, Crested Eagle, Devonia, Gracie Fields and Waverley were lost either from bombardment or by running over the wreck of another vessel which had been sunk earlier.

Many of the smaller vessels were not designed for going to sea. Even most of the paddle steamers had not had peacetime cross channel passenger certificates. The Freshwater normally spent her days flapping her way backwards and forwards across the sheltered Solent. Yet here they were setting off with often inexperienced crews with only a compass, sextant, lead-line, towed log and binoculars for navigation, sailing out from the Thames with all its sandbanks, fast moving tides and hazards to reach the French coast which has its own difficulties of fast tides and shallows, at night and at a time when many navigation mark lights were extinguished in the war time blackout. Then they had to pick up far more troops from the beaches than they were ever certificated to carry by the Board of Trade and do all this under the constant threat of being blown up by mines or bombarded from the air, the land or passing German E-boats. Not a happy prospect.

For all the odds stacked against this evacuation, there was one thing running in its favour. And it was a very big thing. That week was blessed with some idyllic early summer weather. Although there was some wind on some days there was not a lot of it and there were also calm days and balmy night to provide the perfect conditions for putting ships’ bows onto the beaches and for mooring alongside the exposed harbour moles which had never been designed for berthing ships and which were without mooring bollards. If the wind had really decided to blow, particularly from the north, then things would have been very different. There is no way that the ships and boats could have got in and out of the beaches or alongside the harbour moles to pick up the troops with waves crashing onto them as they are so apt to do along that part of the French Coast. Then the story of Dunkirk would have entered history in another way.

Moran Caplat recalled his trip on the Freshwater in his 1985 book “Dinghies to Divas” published by Collins:

Just before my flotilla of launches was to sail from Sheerness and while I was trying to position the compass and wondering how accurate it would be, Lieutenant-Commander Holland-Martin appeared on the dockside and called me ashore. “I’ve got another job for you. These boats can sail under a senior sub in a convoy and follow the others to Ramsgate but the paddle steamer Freshwater needs an officer with recent experience. She’s got her civilian crew but they’ve sent her here with a lieutenant ex RN in charge. He left the Navy some time ago and has only recently been recalled to do a mining disposal course at Whale Island. He’s worried about having to drive Freshwater himself. I want you to join him. By the time she’s coaled, it will be too late for her to get to Dunkirk tonight. Things are so bad now that we can only operate with any hope of getting away with it during the hours of darkness, so you’ll get your sailing orders tomorrow and be going straight to Dunkirk and back to Ramsgate to unload.

I lost my first and, when it comes to that, last command in the Navy and left the launches to chug off with a motley collection of other vessels on the ebb tide to Ramsgate while I joined Freshwater. First we put a lot of things ashore to provide more space and lighten the ship as far as possible, because the plan was to put her bows right onto the beach and have her boarded by soldiers wading out and climbing on the sponsons. Then we inspected the boats and made sure that they could be lowered and used. They were heavy wooden rowing lifeboats stuck in their chocks by paint, and their davits were not the modern self-launching variety. I don’t know when the Freshwater was launched but I am pretty certain that this was not her first war. (In fact Freshwater was launched in 1927 and was a mere stripling of just thirteen in 1940. Although to be fair to Moran, her design was rather antiquated as she was basically an enhanced version of the little Solent of 1902. Ed)

My captain, Lieutenant Church, twenty-odd years my senior, was just as Holland-Martin had described him – long out of the Navy, a worried family man, unhappy at having to go on such a dangerous course as mining in the first place, worried at the responsibility of command, but brave and kind and, I felt, in some way relieved by my youthful enthusiasm for this unforeseen adventure. After a couple of pints in the NAAFI and a canteen meal, we turned in as best we could on the benches in the little bridge cabin while the crew dossed down in the saloon. Nobody left the dockyard and nobody went on the razzle. The atmosphere of Sheerness was too electric. Small vessels, and larger ones, were continuously arriving and what had happened to me, my flotilla and Freshwater and all those involved was being multiplied ceaselessly.

On the morning of June 2 we anxiously awaited our sailing orders. The optimum time to reach Dunkirk was as soon as possible after dark. We realized, though we did not then know how strong the German air attack in daylight was, that we should spend as little as possible of daylight hours within range of the Luftwaffe. Our speed of advance was a maximum of twelve knots but we had to conserve fuel because of our small bunkers, and the Channel tides were a strong force to be reckoned with. We were given a precise time for departure, as was every other craft leaving on a similar mission.

We left Sheerness shortly before noon on a beautiful summer’s day and chugged, as paddle steamers so prettily do, down the swept channel past my old friend the Girdler light-vessel, on past Herne Bay, Reculver, Margate and the North Foreland in the sleepy, balmy, summer dusk. Because of the amount of shipping and the inexperienced crews, more coastal navigation lights than normal were working and the whole picture remains vivid to me.; the calm sea, the occasional flash from a shore light on an otherwise blacked-out coastline, and the rumble of gunfire audible over the rustle of the bow wave and the gentle thud of the paddle wheels.

On our way past the Girlder we took stock of our armament, which consisted of almost nothing. The captain had a service revolver and a few rounds of ammunition issued to him by Whale Island on his departure. We were otherwise defenceless against attack, but I thought that perhaps we could deter the enemy if we appeared to have machine guns on the upper deck. With the help of some of the deck hands, a few broom handles, bits of canvas and the craft of improvisation that several years in the theatre had taught me, we rigged up a number of not very convincing dummy guns at strategic places on the bridge and upper deck, with instructions that if enemy air attack appeared to be imminent, they were to be manned and threateningly manoeuvred. In fact that evening passage to the North Goodwin was totally without incident. We turned to port and headed for France. After it was dark and we were approaching the buoy at Gravelines – the turning point for the inshore channel, which runs parallel with the shore and about two miles off it – the flashes of distant shell and bomb bursts of which we had seen the loom since dusk, became a vivid fire-work display. As we turned into the swept channel shells began to fall around us, not too many and none too near. The firing was obviously un-aimed and indiscriminate; there was no radar in those days so it was a matter of luck. Ours held.

Our orders were to carry on past the entrance to Dunkirk Harbour, where destroyers and deeper draft craft were constantly loading at the quay and ferrying day and night , always under bombardment and in the daylight hours under air attack. The range of our spitfires and hurricanes at that time was just sufficient to fight over the battle front round Dunkirk, but there were not nearly enough of them and reserves had to be kept at home for the defence of England itself. Having passed the harbour we were to go on to the beaches east of Dunkirk towards La Panne, find as many soldiers as we could, get them aboard and beetle off home, aiming to be well beyond Gravelines buoy by full light.

We had no radio or any means of signalling, so we were on our own as far as strategy was concerned. The shelling from behind the shore was constant and it was obvious that a good many shells were exploding on the beach itself where the tide was still rising with an hour or so to go. We were navigating by the seat of our pants, with no echo sounder and no time for a lead-line. We chose a spot about three miles to the east of Dunkirk’s harbour which appeared to have slightly fewer shells falling on it and nosed in to the shore, which there consists of shallow, shelving sandy beach backed by a wide area of sand dunes. About seventy five yards from the beech the keel touched the sand and we went gently astern; the great thing about a paddle steamer is her ability to turn over her big paddle wheels very slowly so as just to inch forward or back. On the other hand, full power can provide a hefty shove and she is just as powerful and manoeuvrable ahead as astern.

We had expected the beach to be crowded with soldiers but it was deserted. I suggested that while the captain continued to manoeuvre Freshwater to keep her afloat but as close to the shore as possible, I should take a boat and go to look for the “silly sods who didn’t know their own luck”. I took two of the deck hands and we were on the sand in no time. The odd shells were coming over and every minute or two one would land out to sea, on the beach not far away, or in the dunes in front of us. Leaving the men with the boat I set off up the beach and into the dunes. I hadn’t gone far when I came across a bunch of Army officers, of what regiment I do not know, sitting in one of the hollows in the sand. There were some other ranks with them too but sitting apart. They were busy eating their rations. They appeared to be surprised that a junior naval officer should suddenly appear and interrupt their meal. When I told them that the Freshwater was handy the senior officer asked how many men we could take. “Several hundred” I answered adding that there were only two lifeboats usable and it would take a long time unless they were prepared to swim or wade out. This they seemed reluctant to do, so while they were debating I moved along the beach and found more soldiers in the dunes. This time they were less disciplined , or perhaps more ready to get out. Anyway, they followed me down to the water’s edge. The two men in the boat rowed her along and the captain brought the Freshwater right in until her bow was just aground. The tide now was almost at its peak. Some soldiers got into the boat, others hung on to the stern and waded out with others following. By the time the boat reached the forward edge of the starboard sponson those wading behind were up to their chins, but we had proved that, even if you were a non-swimmer, you could get to the paddler, wet but safe. We then established the same procedure on the port side and before long had two steady streams of men coming aboard in a orderly fashion. Some brought their rifles, holding them over their heads, some did not. Scrambling on the sponsons was not easy, but with the help of loops of rope and strong arms they managed well enough.

Moving the paddles only gently so as not to create a strong wash, Freshwater kept backing off as the tide began to fall. How long this went on I do not now recall but the stream of men dried up and the tide continued to fall so that eventually with every space bellow decks packed we hauled off and headed back to Dunkirk, made for the Gravelines buoy then turn to starboard and set course for Ramsgate. Such rations as we had were being dished out, and though shells were still falling intermittently and Dunkirk was burning I had a feeling that the mission was accomplished. But all was not yet done.

Other vessels from further along the beach and some from Dunkirk itself were now streaming in steady procession for Gravelines. Dawn was beginning to break behind us. Near the buoy we saw a medium sized French trawler, ahead and to port of us, suddenly go aground. She drew a lot more than we did and was already down to the scuppers in the water. No amount of revving of the screw did anything to move her, either ahead or astern. The tide was falling fast now and when the light came up she was going to be a sitting duck for a German Stuka, so we went alongside her with two or three feet to spare under our keel.

What we expected was that there would be a crew of the trawler plus a few refugees to be taken off. What we got was another matter. The hatches of the trawler were flung open, and on to our deck streamed what appeared to be the better part of the French army, more and more of them. I had not then seen Wagner’s “Flying Dutchman”, but there is much the same effect in the first act when the Dutchman arrives and disgorges a vast chorus of sailors from a rather small stage ship. There was no room for them below decks with us. Both saloons and every space were already filled with tired men and the new men swarmed all over the upper decks, the fo’csle, the stern and wherever they could find a place to perch. Off we went, behind on our schedule and with the paddles thrashing away rather deeper in the water than they were designed to do.

A little way further on and we spotted a Carley life-float adrift. Closing it we was saw two bodies of a British naval officer and a rating, both of whom had died of bullet wounds. The raft showed bullet holes too so it must have been machine gunned. The Germans had a number of E boats operating at night and we concluded that this must be evidence of some engagement.

The Luftwaffe showed up once it was properly light: a two-engined plane circled high above us and then turned as if about to make a run in. There was no point in manning the broom handles now, for the decks were crammed. At that moment the first wave of Spitfires from Kent came screaming overhead on their way to Dunkirk and the German plane obviously thought better of it and made off. That was the end of that and we had no further trouble until mid morning. As we thrashed our way onward, the white cliffs of England hove into view out of the hazy sunshine. With cries of excitement, the French army rushed over to the port side for a better look, the ship heeled violently , the port sponson went right under, the starboard paddle wheel came half out of the water and we careered in a semi-circle like a duck with a broken wing. Shouts from the French officers were not enough; they actually had to draw the stubby little automatic pistols they carried in their belts in order to get their men at gun-point to balance the ship.

And so we made Ramsgate. The berthing officer was a lieutenant- commander wearing his gold lace stripes on the sleeves of a smart blue pin-stripe jacket. Berthing was not easy. We had to wait our turn and finally got alongside another vessel already at the quay. The soldiers, French and British, swarmed ashore across the other vessel and joined hundreds, perhaps thousands more. How those ashore ever managed to get the arrivals sorted out I can’t imagine. Certainly we had no idea how many or whom we had on board.

As soon as we had disembarked our soldiers and two corpses we shoved off. There was no coal for us there, our stocks were low and we were ordered to return to Sheerness forthwith. It was now mid afternoon on 3 June. We paddled quietly back to the Medway, the noise of battle still coming over the water, and discussed how we should conduct the next trip.

At Sheerness once more, late that evening, we were told that we should take coal at first light but meanwhile get some sleep. Next morning we learnt that we would not be going over again, for Dunkirk had fallen to the Germans. In fact the Swastika was hoisted on the eastern mole of the harbour at 10.20am on 4 June. I left Freshwater and Sheerness together that afternoon. Apart from a note hand written by Holland-Martin authorising me to proceed on three days’ leave, my only trophy was a pair of 1900A binoculars taken from round the neck of the dead officer in the Carley float. He had no further need for them but they gave me good service thereafter in the war and ocean racing. I thank him for them often.

After the war and demobbed, Moran had the good fortune to be taken on as an assistant administrator at Glyndebourne Opera. In 1949 his boss, the legendary Rudolph Bing, left to head up the Metropolitan Opera in New York and Moran took over the helm, guiding Glyndebourne for the next thirty years until he retired 1981. Planning, organising the seasons, auditioning, hiring and firing some of the greatest opera singers, directors and conductors of the time were all part of his daily life as was nurturing some of the most outstanding talent of the the future. Both mezzo soprano Dame Janet Baker and bass-baritone John Shirley-Quirk had some of their earliest experiences on the professional operatic stage at Glyndebourne on Moran’s watch.

When he died in 2003, Moran Caplat was the only member of a pretty exclusive club of just one. So far as I am aware, he was the only senior administrator of a major international opera house who, in other lives, had also fixed the lavatory on one paddle steamer and navigated another to Dunkirk.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran