Sixty years ago, 1947 was quite a buoyant year for UK paddle steamers. Although a number had returned from the war in such poor condition that they ended up being scrapped, a lot had been rebuilt, refurbished and returned to passenger service in better condition than they had been before the war courtesy of Government funding . Even four brand new ones had rolled off the stocks in 1946/47: the Bristol Queen and Cardiff Queen for service on the Bristol Channel, the Waverley for the Clyde, and the rather odd Diesel electric roll on roll off Farringford built with independently operated paddle wheels for the Lymington to Yarmouth Isle of Wight ferry.

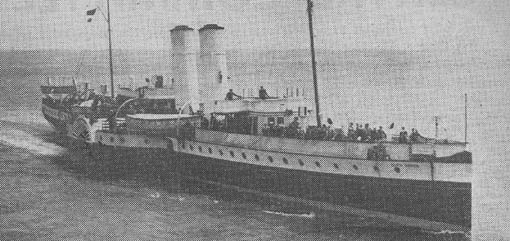

The arrival of the Farringford triggered the first withdrawal of an operational paddler after the war. She downgraded the paddle steamer Freshwater, built in 1927 (pictured above right), to become spare and relief vessel on the route and this put the veteran Solent (pictured above left), built in 1902, out of work. The little Solent spent her whole life in Isle of Wight waters. Before the First World War she made some summer excursions to far flung destinations such as Totland Bay and Alum Bay, all of four miles away from her usual route, and, during the Second World War, she spent some time on the Portsmouth to Ryde ferry. But it was on the thirty minute crossing between Lymington and Yarmouth that she spent the vast majority of her career. Backwards and forwards, backwards and forwards and backwards and forwards again. And that was only before lunch.

After lying idle for some while, the Solent was sold in 1948 for scrap to Harry Pound of Portsmouth but defied the breaker’s torch for a while by being snapped up for a new career as a transport cafe and lodging house for lorry drivers at Porchester (pictured above). Rejoicing in the new and doubtless apt name of Bert’s Cafe she continued to serve teas until late 1958 when Bert switched off his urn and the breakers moved in.

Ten year later in 1957 three more paddle steamers were withdrawn: the Bournemouth Queen as recounted last month, the Glen Gower (pictured above) and the Jupiter. Built in 1922, the Glen Gower, or “Galloping Gertie” as she was sometimes called, ran on most of P & A Campbell’s routes in the Bristol Channel and on the South Coast where she also had cross channel passenger certificates which took her to Boulogne as late as 1956. By 1957, P & A Campbell were getting into serious financial difficulties. The Glen Gower retreated to the Bristol Channel for her last summer after which she was laid up. Three years later she was towed away to be scrapped in Belgium.

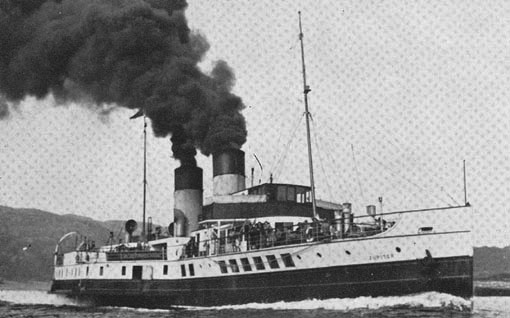

Third to go in 1957 was the Jupiter (pictured above). She was built in 1937 for the LMS railway upper Clyde ferry services from Gourock and Wemyss Bay for which her large passenger capacity of 1,500 made her most useful at peak times. She returned to her old routes after war service but her future became more uncertain as car ferries and the cheap to run Diesels appeared on the Clyde in the 1950s. Looking back through the records it is surprising to see that she was converted from coal to oil burning in the spring of 1957 which makes her withdrawal after only one season with the new kit seem a bit wasteful. It is difficult to imagine a private company, rather than the nationalised industry which owned her, doing that. After lying idle for nearly four years, the Jupiter was towed away to be scrapped in Ireland in 1961.

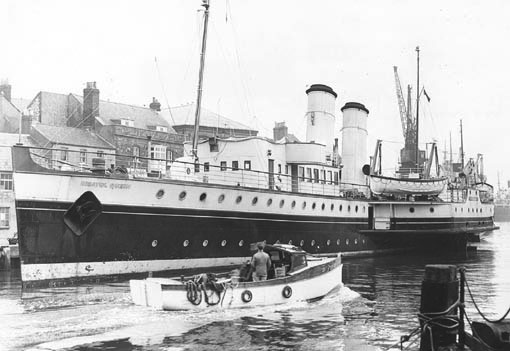

Ten years on in 1967, two more paddle steamers were withdrawn, the Queen of the South (pictured above) ex Jeanie Deans and the Bristol Queen. Built in 1934 for the LNER railway ferry and excursion services on the Clyde, the Jeanie Deans was withdrawn in 1964 but bought for a new and disastrous career as a Thames excursion steamer sailing under the new name of Queen of the South. If anything could go wrong with this venture as well as a lot that you couldn’t possibly imagine would, it did go wrong in spades and the ship sailed on only a handful of days in 1966 and 1967 as she staggered from one breakdown to the next. After being arrested by an Admiralty Marshall for non-payment of debts, the ship was towed away in December 1967 to be scrapped in Antwerp leaving much unhappiness and many broken dreams in her wake.

Last to go in 1967 was the Bristol Queen (pictured above in Weymouth Harbour in the winter of 1962/63). She was built in 1946 for P & A Campbell’s Bristol Channel services and became their last paddle steamer in 1967 after the withdrawal of her near sister the Cardiff Queen the previous year. Sadly 1967 was not a good summer and despite a lot of money being spent on the ship in the previous winter refit she suffered from various mechanical problems culminating in a major breakdown in late August. She was towed away to be scrapped in Belgium in March 1968.

After that there were only nine operational paddlers left in the UK, all of them owned by outposts of the state: the Ryde at Portsmouth, the Farringford at Lymington, the Cleddau Queen, operating the Neyland ferry, the Caledonia and the Waverley on the Clyde, the Maid of the Loch on Loch Lomond and the Tattershall Castle, the Wingfield Castle and the Lincoln Castle running on the River Humber ferry service between Hull and New Holland.

Picture of Bert’s Cafe from the Jill Harvey Collection.

Geoff Hamer wrote on 1st September 2007:

As usual, I enjoyed looking at your pictures of the month. I note your comment that no private company would have spent money on a conversion to oil firing one year before withdrawing the JUPITER. Later you comment on the amount Campbells spent on the BRISTOL QUEEN months before her withdrawal. They had also spent money on buying oil-firing equipment for the GLEN USK which was never used – at least the JUPITER did actually use hers.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran