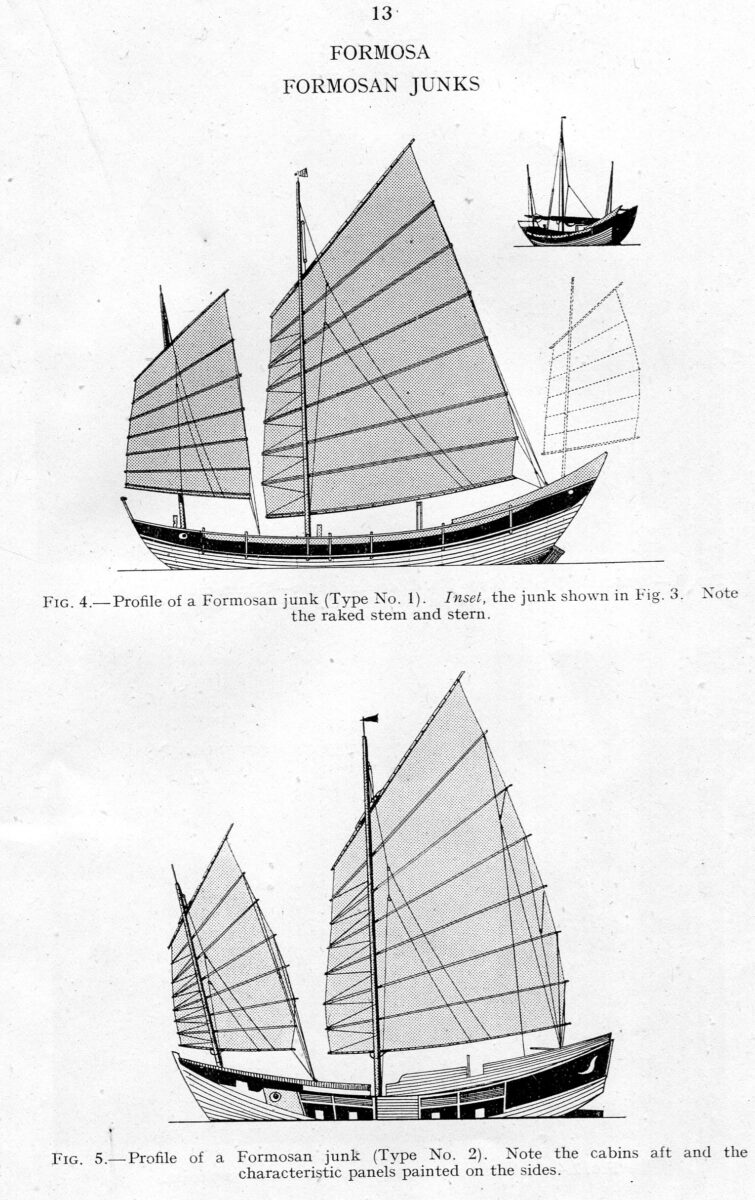

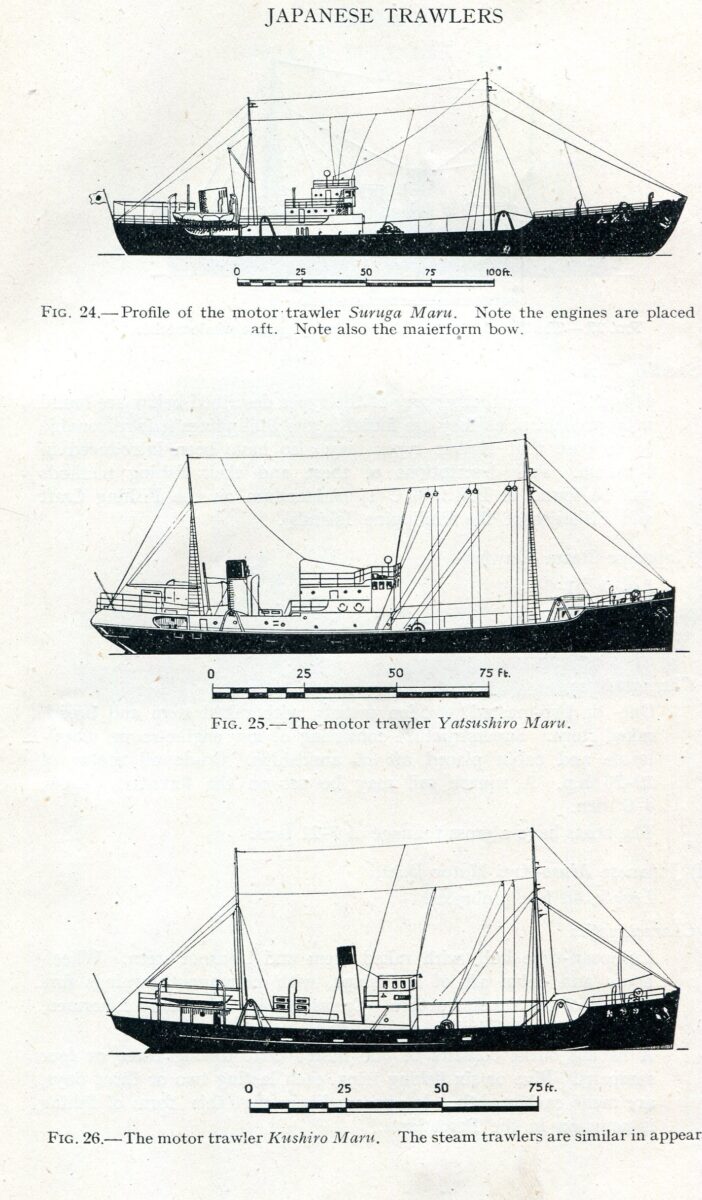

I have here with me a very large box stuffed full of hundreds of photographs of Chinese, Burmese and other Junks plus other disparate Far Eastern Craft including the ship recognition books associated with them published by the Admiralty during the Second World War to help allied shipping and aeroplanes identify enemy craft. All are illustrated by my father the late Winston Megoran.

The photographs were taken by allied agents and other sympathetic parties in the Far East and came to London for analysis by a small team led by Bill Reiss at the Admiralty in Whitehall. They had to drill down to see what the pictures might reveal, when were they taken, where were they taken, what time of day they were taken. Is there a clock in the background to fix the time for certain? Where is the sun. Who is in the picture and what are they doing. Are they trying to conceal anything? That sort of things and so on and so forth.

Ship recognition books were then prepared from the photographs for distribution to ships and air stations and for these Dad drew the illustrations. Bill was best man at my parent’s wedding just after the war and ended up as a Keeper at the Natural History Museum. Dad continued to earn a living as a marine artist and finally as a teacher of art.

Thinking about Dad and these books I decided that it might make a change from the usual Pictures of the Month to take a couple of pictures of Cosens’s Monarch and try to apply Dad’s analytical picture skills to them and see where that gets us.

So here goes. This is Monarch alongside the Pleasure Pier at Weymouth in February 1961 shortly before she was towed away to be scrapped in Cork. You can see the Stone Pier on the other side of the harbour with its distinctive harbour wall and railings which confirms the position. This berth is the one Waverley has used in recent years but before it was extended out a bit as part of the construction of the new terminal for the first drive on Channel Island car ferry Falaise at Weymouth in 1973. The sun is on the right throwing shadows to the left so given that the berth extends roughly NE/SW we are past midday and probably in the early afternoon.

Next take a look at the ship’s railings. Take a good look. I will come back to them later.

What else can we see? On the left is the galley chimney for the coal fired range which shows that a galley is just below it. That’s the only galley chimney in this picture but we know that Monarch had two galleys. This one, which was used primarily as a crew mess room in later years, and the main one abaft the paddle box on the port side.

There is a ladder up the funnel to the whistle and siren. Monarch was the only paddle steamer in the Cosens’s fleet to have this facility. On the others if ever there was a need to get up there a separate ladder had to be fetched for the task. But this didn’t matter much as by then Cosens had the whistles and sirens all painted silver so there was no need for anyone to go up rag in hand with a tin of Brasso on polishing patrol.

Look behind the ladder and you can see the lagged pipe taking steam up to the whistle. You can also see that at the bottom there is a sort of kink in it. This I think was quite deliberate. In a straight line up and down pipe some steam may condense and fall back down the pipe sitting there as hot water doing nothing so when the whistle is blown this is then fiercely blown up the pipe ahead of the steam to spray out from the whistle over passengers in the vicinity before the steam gets to it to give the required blast. The kink, which on some ships is routed almost as a circle, gives any condensate a slightly longer and more circuitous route up the pipe to the whistle thereby giving any hot water in the system the chance to be heated up by the flowing steam and therefore turned back into steam once again before it reaches the whistle giving a cleaner blast.

You can see that there are four funnel stays two leading forward and two aft to help keep it steady and relieve the pressure on the bolts holding the funnel onto the fiddley.

You can just about make out a small set of steps up onto the fiddley. Why were they there? Why did anybody want to climb up there sufficiently often to require permanently fixed steps? Well as built as Shanklin in 1924 for the Southern Railway route between Portsmouth and Ryde, the entrance to Monarch‘s bridge was at the aft end with another set of steps from the fiddley upwards into it in the middle. This route to the bridge continued after Monarch acquired a wheelhouse which had a door in the back of it for access. This was changed in the mid 1950s when that door was blocked off and a ladder positioned from the promenade deck straight up to the aft end of the starboard bridge wing instead. That ladder is not in sight in this picture revealing another of Cosens’s long lost secrets. Sometimes, but not always, these ladders were removed in winter not only to make access to the bridge harder for any poor and uninvited wandering ones coming aboard during the dark days of winter from going up there to take a look but also to protect the varnish of the ladders from the wind and the rain. This is a tradition I continued with KC. “End of season. Ladders into the stores.”

Now let’s look at the bridge. The door as you can see is of the swinging on hinges type rather than sliding. One downside of that is that if it is not hooked open properly it may swing and bang and in the worst case scenario maybe even trap someone’s fingers. Ouch! Many paddle steamers had sliding doors which avoided this but not Monarch or indeed another Weymouth based paddle steamer of my youth Princess Elizabeth. On my first trip on Monarch as a boy in 1960 I was up on the bridge as we came up to berth at Bournemouth Pier starboard side to ine afternoon. Mate Arthur Drage left the wheel to open the port door. My younger self asked him why he did that when we were coming in starboard side to. He replied that they always had to have both doors open when berthing just in case he of Capt Defrates had to go out onto the port wing to check anything.

That was good practice I thought. KC has just the one door cut into the aft section of her wheelhouse on the starboard side. However when that is hooked open at the back the whole aft section of the wheelhouse could be slid to starboard on inbuilt rollers thereby providing a door opening on the port side. Cunning people those ship designers in Devon.

Let’s next look at the engine room and docking telegraphs on the starboard bridge wing. What do they tell us? Well the first thing to notice is that the canvas covers only go over the tops and do not extend over the pedestals revealing that, horror of horrors, the pedestals are painted. Because the picture is in black and white we can’t tell the colour but I remember that they were brown. Painting brass telegraphs was quite common on railway owned ships back then. I remember that they were brown on the Channel Island cargo boats Roebuck and Sambur at Weymouth with silver painted handles. Ryde’s telegraphs were painted grey. And so on. But the brass on Cosens’s paddle steamers usually sparkled and so it did on the Monarch’s bridge too insofar as the upper parts of her telegraphs were concerned. The tops were polished but the pedestals remained painted throughout Monarch’s career with Cosens.

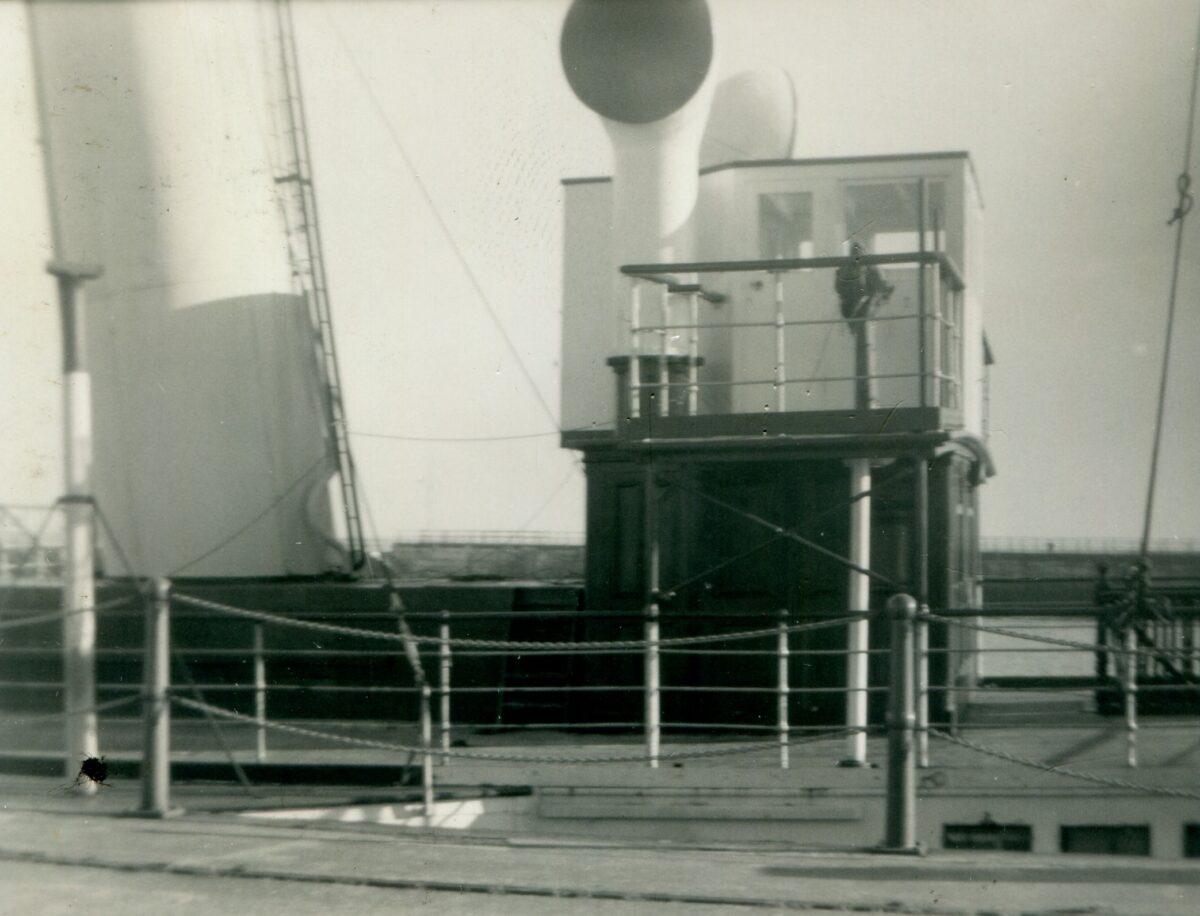

Here is another picture of Monarch taken on the same day. Starting at the top you can see the crane on the top of the funnel for hauling up the second steaming light. Prior to 1954 vessels of Monarch’s size only required one steaming light plus the port, starboard and stern lights. After 1954 they needed two and the crane was a cheap and easy way of fitting one. It meant though that the light could not be powered by electricity due to the close proximity to the hot gasses coming out of the funnel to any necessary electrical cables so it remained lit by oil. The lamp was stowed just abaft the wheelhouse and hoisted and lowered by a seaman as required.

You also get a better view in this picture of the funnel stays and the telegraphs. Look on the port bridge wing on the right and you will see a voice pipe. This was an unusual placement for a UK paddle steamer outside the wheelhouse.

Now look at the pole mast which as you can see is at the forward end of the promenade deck. It has two forestays, two backstays and two shrouds each side with a block on the lower forestay to take a halyard to hoist a ball or an all round white light by night when at anchor. There is a halyard each side to raise flags. All the stays, with the exception of the forestays, are clear of the foredeck. Shanklin’s immediate predecessor Duchess of Norfolk, also built for the Portsmouth/Ryde route and which became Embassy, had her mast a few feet further forward sited on the foredeck with her shrouds coming down onto a position on the top of the bulwarks either side. Maybe they were a little bit in the way there for cargo handling as the Portsmouth paddlers used the foredeck for storing baggage, parcels and the like swung aboard by small shore based cranes at Portsmouth and Ryde. So placing the mast like this on Monarch a few feet further aft would have helped to keep the rigging clear of cargo movements.

Now look at the doors to the accommodation. Why is one so much bigger than the other? Well that’s also to do with the movement of baggage. You can get more trunks and assorted parcels in and out of a bigger door more easily and faster than a smaller one.

Next to the mast you can see a large white pencil shaped structure next to one which looks a bit like an odd shaped mushroom. As built Shanklin was at the cutting edge of technology being fitted with a sort of early air conditioning/heating system which sucked in air via this kit and then distributed it around the ship through pipes.

Take a look along the line of the bulwarks and you will see two openings or scuppers to let water out from the foredeck. It was never very likely that Monarch would ever ship any serious green seas on her foredeck on the services for which she was designed and built but some water might have come over and from time to time did. That washed overboard through these scuppers. Also water could come onto the foredeck up through the hawser pipe for the anchor. I remember many a trip on the Embassy, which had a similar arrangement, in my youth and watching as the bow dipped into a sea off the Needles the water spouting on up through her hawser pipe and washing over people’s feet standing on the foredeck in the vicinity and not expecting it. A cause for much merriment and mirth in some I think.

This picture of Embassy reminds us that there are many ways of skinning a cat. Both Embassy and Monarch had the same basic hull shape and structure. They had pretty much identical dimensions. They were built for the same route. Their bridges had the same footprint but they both acquired completely different wheelhouses designed by different people in different yards at different times. Here on Embassy there are four windows in the front and the whole structure is varnished. Monarch had only three windows in the front of hers and the whole of her wheelhouse was painted white. Embassy’s is rectangular in shape. Monarch’s is rectangular in the front but at the back sort of moulds itself with nice curves around the boiler ventilating cowls.

Let’s now get back to the railings where we came in. Embassy’s were pretty much identical to those on Monarch. Did you notice anything special about them when you first looked? I expect you did. Two things actually.

Firstly the railings around the promenade deck have no wooden handrail capping them. The top rail is just a steel bar, slightly thicker than the other bars to be fair, but just like on KC a bar nonetheless. And wooden tops to rails are labour intensive in terms of maintenance with sanding and varnishing every year and so on. Is that really necessary on a ferry built for a thirty minute crossing backwards and forwards across the Solent? Clearly the Southern Railway, like their predecessor companies, thought not.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the number of horizontal rails is different on the passenger promenade deck, where there are four such bars, than on the bridge, which is restricted to use by the crew, and where there are only three. It has ever been the case from the old Board of Trade days right up to the MCA of the present that the requirements for railings differ in passenger and crew areas with the latter being less onerous.

Fewer rails is of course a bonus when a ship is being built as it provides a cost saving but more than that it saves weight and naval architects are always looking to find ways to save weight on ships as the more unnecessary weight a ship carries then the more fuel it needs to burn to push it along and the lower it will sit in the water.

So there we have it. A “My Dad” style analysis of pictures of the Monarch. That’s just how he used to go through pictures with me as a child. And I am so very grateful to him for encouraging me to drill down like this and to try to see what is going on, what can be revealed in the background and what we can find out from them about the past. I just love doing it. I hope you do too.

As to the contents of that box which so exercised Dad’s judgement and skills nearly eighty years ago during the Second World War, I just don’t know quite what to do with it now. I guess that there may be Chinese Junk enthusiasts out there who would drool at the thought of pouring over all those images of minor differences between the multiplicity of Far Eastern local fleets of yesteryear but I don’t know any. Do you? If anybody does have any ideas or suggestions then do let me know: jhm@kingswearcastle.co.uk

And don’t forget that we are still fund raising for the second phase of Kingswear Castle’s major rebuild. Do help if you can. To find out more click here.

Thank you.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran