Wars are pretty unpleasant for all who get caught up in their trail of killing, blowing up and destruction. But there are those for whom wars are seriously good news. Weapon manufacturers can’t get enough of them to shift on their products. States may wish to gain access to coveted raw materials in other states. And, in our own little world of boats, it is manna from heaven for shipyards to have the vessel which they have just built torpedoed shortly after commissioning necessitating an immediate repeat order for which they would normally have to wait a further twenty or more years. Things like that don’t happen in peacetime. Do they?

Well, the answer is: sometimes they do. Even big, state of the art ships occasionally come to grief pretty early in their careers (remember the Costa Concordia); some, like the Titanic, even earlier, have sunk on their maiden voyage; and a tiny number earlier still before anyone has even got round to thinking about something so far down the line as a maiden voyage.

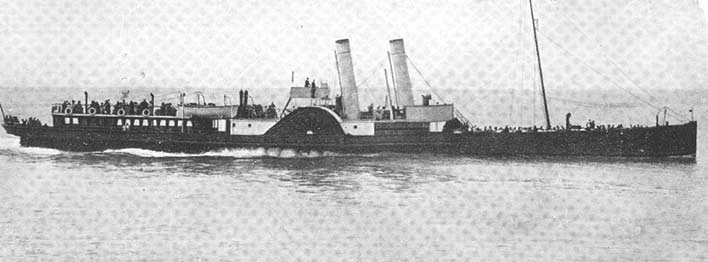

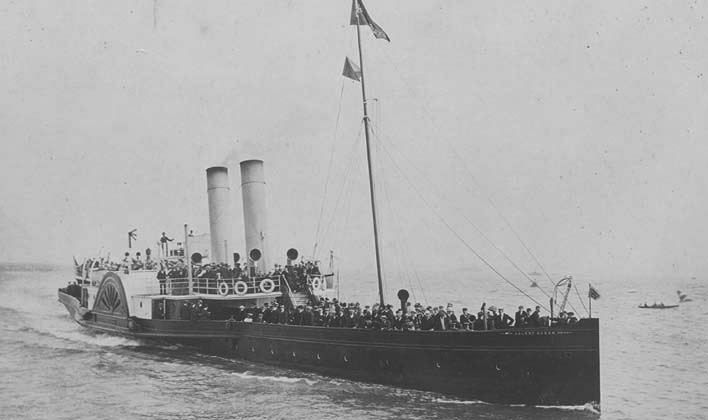

One such was the paddle steamer Princess of Wales ordered from the Clyde yard of Barclay, Curle & Company in 1888 for, what is now called, Red Funnel’s Southampton to Cowes ferry service. She never came anywhere near to seeing Southampton, Cowes or anything further south than the Cumbraes sinking instead on her builder’s trials. So early in her career did she meet her demise that there don’t even seem to be any photos of her either. The picture above is of the Solent Queen which was subsequently built along very similar lines.

Shiny and new, the Princess of Wales set off on 16th June 1888 for speed trials against the measured mile off Skelmorlie where she encountered the 2,058 ton former Castle Line steamer Balmoral Castle (pictured above) also out on trials. Some confusion seems to have arisen between the pilots on the two ships with the result that the liner ran straight through the paddler just abaft the paddle box slicing her in half. The stern section sank straight away sadly taking three of the shipyard painters with it. The bow section was taken in tow but did not make it far before it too sank.

The inquiry was heard before Sheriff Mair, in the Sheriff Court, Glasgow, on the 16th, 17th, 18th, and 19th days of July 1888 and this is the report:

Mr. C. D. Donald appeared for the Board of Trade, Mr. John A. Spens for the owners of the “Princess of Wales,” Mr. Henry Roxburgh for the owners of the “Balmoral Castle,” Mr. H. B. Fyfe for the pilot of the “Princess of Wales,” Mr. Thomas A. Fyfe for the pilot of the “Balmoral Castle,” Mr. J. B. Sutherland for Captain Chapman of the “Balmoral Castle,” and Mr. James Donaldson and Mr. Hugh Moncreiff for other parties interested.

The “Princess of Wales” was a paddle steamer, built by Messrs. Barclay, Curle and Co., Limited, Whiteinch, for passenger service between Southampton and Isle of Wight, and was of the following dimensions:-215 ft. in length; 21 ft. in breadth; and 8 1/2 ft. in depth. She was still in the hands of the builders when she left Glasgow on the 16th, but appears to have been fully equipped in respect of engines, deck gear, and boats, of which there were three, two in the after end and one on the bridge. She was under the charge of Mr. James Barrie, a Clyde licensed pilot, who had 15 years’ experience on the river, for the purpose of testing her speed and other qualifications over the measured mile at Wemyss Bay. She had on board a full complement of hands on deck and in the engine-room, besides a number of guests.

The “Balmoral Castle” is an iron screw steamer of 2,058 tons register, built in Govan in the year 1877, and her dimensions are as follows:-Length 344.8 feet, breadth 39.4 feet, and depth of hold 29.1 feet. She had just been fitted with triple expansion engines and new boilers by Messrs. David Rowan & Son, under contract with Messrs. McMillan & Co., Dumbarton. She had six boats, four of which were lifeboats, and two ordinary boats, all of which appear to have been fully equipped and ready for service, they having been examined and passed by the Board of Trade surveyor at Glasgow. She was under the charge of Mr. James Parker, a Clyde licensed pilot of 10 years’ experience on the river, with a sufficient complement of men to work her on deck and in the engine-room; there were also Captain Chapman and a crew of runners on board, who were under contract with the builders to bring the vessel from Greenock to London after completing the trial trip.

Both vessels started for their trial trips from Glasgow on the morning of the 16th June 1888-the “Balmoral Castle” for the purpose of adjusting compasses as well as to run the measured mile, the “Princess of Wales” merely to test the speed and working of her engines.

At about 12.40 p.m. on the same day the “Princess of Wales” arrived at the southern end of the measured mile, and made one run downwards, and having accomplished the run in a satisfactory manner, turned round and came up the mile, going on what was termed her dead slow trial. The weather at this time was fine, with a light wind from the eastward, and the sea smooth. Soon after this the “Balmoral Castle” was observed turning on to the mile at the northern end. A preliminary run along the mile from south to north appears to have been made by the “Balmoral Castle” at full speed, and she was again turned on to the mile to make the southern run, still going full speed. Both vessels appear from the evidence led to have taken up the same line of course along the land, from which they were distant a quarter to half a mile. It was admitted by the pilots of both vessels that they were end on, or nearly end on, to each other, when the “Balmoral Castle” straightened on the mile, the distance between them at that time being about three quarters of a mile.

Mr. Barrie, the pilot of the “Princess of Wales,” stated that when he first saw the “Balmoral Castle” enter the mile she was nearly right ahead, but seeing the “Balmoral Castle” port, he ported a couple of spokes, but before his helm could have taken effect he observed the “Balmoral Castle” swinging to starboard, and, as he expressed it, he now saw “that something must be done,” upon which he ordered his helm hard-a-starboard, to pass on the starboard side of the “Balmoral Castle,” but he had no sooner done so than he noticed that the “Balmoral Castle” was porting her helm and heading right for him. The head of the “Princess of Wales” had swung about 3 points to port, when he ordered the engines full speed ahead, in the hope of clearing the “Balmoral Castle,” but was struck almost immediately after just abaft the starboard sponson, at an angle of about 45°, with such force that she was cut right through, completely separating the after from the fore end. Most of those on board on the after end of the “Princess of Wales,” seeing a collision inevitable, ran forward and thus saved themselves, but unfortunately three men who were working in the saloon went down with the after end, which sank in a few seconds, and their bodies have not been recovered. The after-bulkhead of the engine-room remained intact, and kept the forward end afloat until those on board, as well as some who were clinging to the wreckage of the after part, were taken off by three of the “Balmoral Castle’s” boats, and some small boats from the shore.

Mr. Parker, pilot of the “Balmoral Castle,” admitted that when he entered on the mile he observed the “Princess of Wales” coming up the mile end on, or nearly end on, to his vessel, and that his first order to the helmsman after straightening on the mile was, steady port, and that he gave no other order beyond “port a little more” until he saw the “Princess of Wales” starboarding, then he ordered the helm “hard-a-port.” Up till this time he had no thought of a collision; but seeing the “Princess of Wales” starboarding and increasing her speed, and that a collision was inevitable, he telegraphed “full speed astern”; but the “Balmoral Castle” struck the “Princess of Wales” before the engines could be stopped. According to the evidence the “Balmoral Castle” forged ahead about a quarter of a mile after the collision, with her engines going full speed astern. The “Balmoral Castle’s” boats were promptly lowered, and assisted in rescuing those on board the “Princess of Wales.”

Mr. Donald, for the Board of Trade, asked the opinion of the Court upon the following questions:

- What was the cause of the collision between the “Balmoral Castle” and the “Princess of Wales” on the 16th of June 1888?

- Did both vessels comply with the Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea?

- Particularly did both vessels comply with Article 15 of the said Regulations when they approached each other on the measured mile at Skelmorlie?

- Was the pilot of the “Princess of Wales” justified in starboarding his helm shortly before the collision, and did his doing so contribute to the collision?

- Did both vessels duly conform with Article 18 of the said Regulations, or, if not, was such non-compliance justifiable?

- What was the cause of the loss of the “Princess of Wales?”

- What was the cause of the loss of life?

- Were both vessels navigated with proper and seamanlike care?

- Whether the master and pilot and mate of the “Princess of Wales” and the master and pilot of the “Balmoral Castle” are, or either of them is, in default?

- In the opinion of the Board of Trade the masters’ certificates of the pilots in charge of the “Princess of Wales,” the mate of the “Princess of Wales,” and the master of the “Balmoral Castle” should be dealt with?

The Court gave judgment as follows:-

- The Court is of opinion that the collision between the “Balmoral Castle” and the “Princess of Wales,” when running the measured mile in Wemyss Bay, was caused by the neglect of the pilots of both vessels in not stopping and reversing when there was a risk of collision.

2, 3, and 5. The “Balmoral Castle” and “Princess of Wales” were approaching each other nearly end on. The “Balmoral Castle,” according to the evidence, complied with Article 15 in porting her helm; but the Court is of opinion that had more port helm been given at first there would have been little risk of collision, as it would have been clear to the pilot of the “Princess of Wales” what the “Balmoral Castle” was going to do. The “Princess of Wales” did not comply with Article 15; her helm was, according to the evidence, put two spokes to port, but immediately changed to starboard. it must then have been evident to the pilots of both vessels that this manoeuvre would probably result in a risk of collision, and the Court is of opinion that both vessels should have complied with Article 18 by stopping and reversing, which they failed to do.

- From the evidence led there does not appear sufficient reason to justify the pilot of the “Princess of Wales” in departing from the rule of the road respecting two steam vessels meeting end on, or nearly end on, and his having starboarded his helm did, in the opinion of the Court, contribute very materially to the collision.

6 and 7. The cause of the loss of the “Princess of Wales” was her having been cut through abaft the starboard sponson by the “Balmoral Castle,” the after end being separated from the fore end, and sank a few minutes after, unfortunately carrying with it three tradesmen who were at work in the saloon.

- Having regard to the previous answers both vessels were not navigated with proper and seamanlike care.

- The pilots of both vessels are in default, but as this Court has no jurisdiction with regard to their licenses, it can only express its astonishment at their want of care and skill. The mate of the “Princess of Wales” was absolutely under the direction of the pilot. Captain Chapman was to all intents and purposes the master of the “Balmoral Castle,” his name was on the register as master, he was also in the pay of the owners during the alterations, and had a full crew of runners, who were under agreement with him to take the ship to London, and who were on board at the time. It was contended that there was a compulsory pilot on board the “Balmoral Castle,”-but the ship was not in “compulsory pilotage waters”-and if she had been, the Court fails to see how Captain Chapman can be exonerated from taking a share of responsibility for this unfortunate casualty, resulting not only in the loss of a valuable ship and three lives, but almost in the loss of all on board the “Princess of Wales.” But under the circumstances the Court does not deal with his certificate.

Barclay, Curle was acquired by Swan Hunter in 1912 and, after a series of other mergers over the years, was eventually swallowed up into the Seawind Group which still exists today well over a hundred years after the original shipyard’s unexpected windfall repeat order after the sinking of the Princess of Wales in 1888, no wars necessary this time.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran