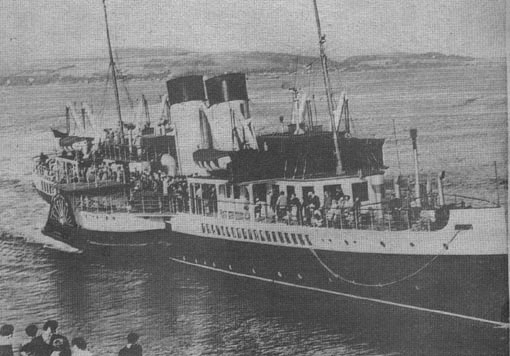

As part of Dr Beeching’s Draconian pruning of the British railway system, the Clyde lost two of its veteran steamships after the 1964 season, the turbine steamer Duchess of Montrose and the paddle steamer Jeanie Deans (pictured above). Both lay in the Albert Harbour throughout the summer of 1965 as their consorts jollied their way around the usual summer piers. Duchess of Montrose was sold for scrap and left the Clyde on 19th September for Ghent. Most people assumed that the same fate would befall the Jeanie Deans but a knight in shining armour rode onto the scene in the form of Don Rose who, with a consortium of businessmen, bought the ship for further service. Don had a long standing interest in paddlers and had previously chartered both the Medway Queen and the Consul for special sailings on the Thames. He was determined to do something to secure a future for the Jeanie Deans.

For his dynamism, ideas and will to succeed, Don cannot be faulted. But the Jeanie Deans required a lot of very major work and hence a lot of very major money spending on her to put her back into any sort of reliable service. Manning a paddle steamer for a very specialist operation dashing in and out of umpteen piers every day, all of which have their own tidal and wind vagaries, and keeping to schedule is also not easy. And the balance between income and expenditure for a paddle steamer operation is fine. As Mr Micawber said from the experience of his own financial chaos “Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen pounds, nineteen shillings and six pence, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds and annual expenditure twenty pounds nought shillings and six pence, result misery.” The Jeanie Deans move south caused Don and his associates a very great deal of the latter.

Don started out on the right foot by hiring a captain who had been master of a paddle steamer before, Stanley Woods, pictured above on the bridge of the Princess Elizabeth at Weymouth in 1965. A deep-sea man with a master’s ticket in both steam and sail, Capt Woods had been mate of the Consul on the Sussex coast in 1963, mate of the Princess Elizabeth for part of the 1964 season and in 1965 he took command. It was then that I got to know him and that is how I came to have a fleeting and youthful involvement in the attempts to put the Jeanie Deans back into service.

In October Capt Woods wrote to me about the new project asking if I would like to join him for the voyage south from the Clyde. Yes, was the most emphatic answer and, with the sort of good fortune which was not to be a feature of Jeanie Deans’ career over the next two years, the trip turned out to be scheduled in my school half term holiday so my parents agreed to let me go. On Monday 1st November 1965 I therefore took the train to London with two ABs from the Princess Elizabeth, Ken Moore, son of a former Cosens master Capt Pony Moore, and Alfie Le Page who had been with Cosens for much of his working life and looked to my young eyes to be aged somewhere in excess of 108. We were joined at Southampton by Capt Woods and from London we flew up to Glasgow to join the ship at Lamont’s Shipyard at Port Glasgow just as dusk fell.

Compared with the Weymouth paddle steamers I had known, Jeanie Deans was absolutely huge with her two great funnels, enormous triple expansion engine and a bridge equipped with the modern wonder of radar. Much work had been done to prepare the ship for her new life but she was in a poor state generally. The decks leaked. There was the accumulation of more than a year’s dirt everywhere. The cabins, including the mattresses, were damp. Capt Woods promptly abandoned any thought of moving into the captain’s cabin abaft the wheelhouse and immediately decamped to a hotel ashore at the company’s expense, commandeering the purser’s office with its steel, and hence watertight, deck-head for his use in due course. I was less lucky and made my bunk on a moderately dry settee.

The following morning Jeanie Deans shifted ship from Lamont’s jetty into their basin for additional work with a great deal more shouting of orders from ashore and on board than I had previously heard in paddle steamer manoeuvring. On the Wednesday we were ready for trials and, with a pilot aboard as well as Don Rose clutching a plate of delicious smoked salmon sandwiches, we backed out into the Clyde and proceeded down river. Jeanie Deans was still capable of a good turn of speed and easily overtook one of the Gourock to Dunoon ferries but there were lots of things that were not quite right. When the whistle wire was pulled to give a cheery blast it came away in Capt Woods hand. When the fire hydrants were tested, not only did the hose pipes leak but so did some of the steel pipes feeding them. The list of defects was long.

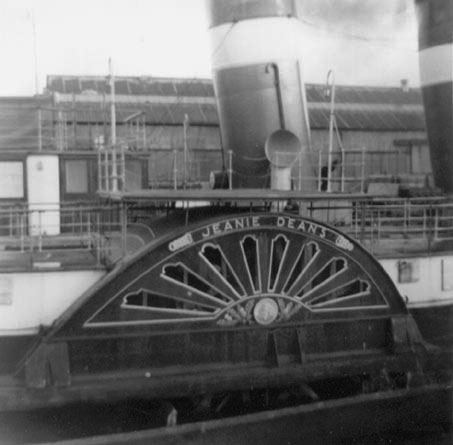

Jeanie Deans returned in the early afternoon to lie alongside at Greenock where she is pictured above with the windows and portholes well boarded up for the journey south. The boarding up was very extensive and included having curved steel plates welded in place around the windows in the forward deck shelter. This caused our Clyde pilot to ask if the plan was to steam her across the Atlantic rather than round the coast to Chatham.

During the Thursday afternoon bunkers were taken and, as it turned out, rather more bunkers than planned. Shortly after the above picture was taken heavy fuel oil started to squirt out from the overflow pipe, which can be seen running up the side of the funnel, narrowly missing the assembled crew (including Alfie Le Page with a slight stoop on the right) precipitating another bout of various levels of shouting.

Departure was now scheduled for Friday November 5th but there was a further delay whilst the Chief Engineer was taken to hospital in an ambulance with stomach pains. An engineer was hastily drafted in from Lamont’s to take us as far as Stranraer to train up the Second Engineer in the mysteries of Jeanie’s engine room and, at last, we sailed about tea-time. We sped along in the gathering darkness until, off Dunoon, the paddle beat got slower and slower and slower and a message came up to say that the boiler water feed pump was not working and the boiler was nearly out of water. We dropped the anchor and enjoyed the modest Guy Fawkes fireworks displays on each bank of the Clyde whilst the engineers fixed the problem. After an hour or so the anchor came up and we continued until we were off Pladda when, again, the paddle beat got slower and we were forced to stop for more remedial work. I remember Capt Woods looking rather anxiously at the chart, commenting on how deep the water was even close up to the shore in places and wondering if there was anywhere near enough chain in the locker to drop the anchor out here. Fortunately the engineers got things going and, around midnight, we came to anchor off Stranraer to await daylight to go in, drop off the Lamont’s engineer and pick up more water.

Amongst the multiplicity of changes which have overtaken us in the last fifty years, one has been the development of radio communications. In 1965 VHF for inter-ship and port radio, for example, was in its infancy with few ships having it fitted and, although sea-going paddlers like the Jeanie Deans were equipped with medium frequency radios, their regular use was much discouraged as the broadcast range was so large that the whole system would have clogged up if too many people had used it too often.

The staff at Stranraer were therefore much surprised to find the Jeanie Deans steaming up to their jetty unannounced early on the Saturday morning. A management figure promptly emerged to tell us that there was no way that we could moor on the western side where we were trying to tie up as this was where the mail boat berthed. Dutifully we backed off and re-moored on the eastern side. The same man then re-appeared to ask what we wanted. Water and lots of it was our primary need but it turned out that there was no hydrant on the east side. We would have to back off and come in again on the berth we had just vacated where the hydrant was.

There are many ingredients in the fortunes of any venture. The necessary skills, hard work and plenty of cash to dig yourself out of holes are just some. But a measure of good luck is always beneficial in any equation of success and that was something which seemed to be in very short supply for the Jeanie Deans then and for her following two seasons as the Queen of the South. The wicked hobgoblin who turns well meant decisions into black farce seemed to have stationed his malevolent wand permanently round each and every corner.

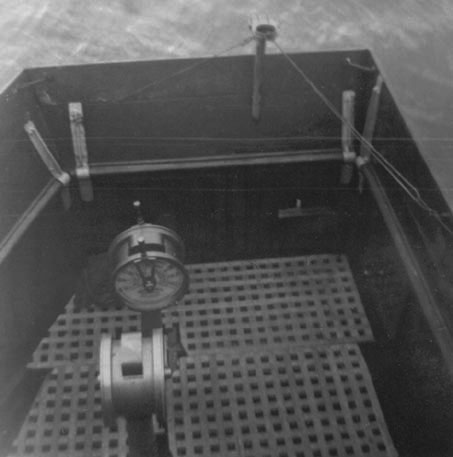

As it was now Saturday and I had to be back at school on Monday, with the very greatest reluctance, I paid off. The crew, meanwhile, were busying themselves filling every available receptacle with spare boiler feed water for the onward voyage “just in case” including the lifeboats (pictured above) which, being rather dry, were passing it straight out again through their clinker built boards.

Later Jeanie Deans continued on her passage to the Medway where she arrived on Sunday 14th November to lay up for the winter on the buoys off the Gun Wharf at Chatham (pictured above) not a million miles from Kingswear Castle’s old berth at Thunderbolt Pier. I returned home and to school.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran