Why did some paddle steamer boilers last longer than others? How come some elderly paddle steamers with careers way beyond their design lives took the same boiler with which they were built to the scrapyard with them whilst others required multiple boiler replacements in careers of similar or shorter lengths. What was going on here?

Waverley’s original boiler lasted for thirty four years until 1981.

Kingswear Castle’s original boiler dating from 1924 lasted for thirty seven years to 1961.

Princess Elizabeth’s original boiler dating from 1927 lasted to the end of her operational career in 1965. That’s a thirty eight year career

Embassy took her original 1911 boiler with her to the scrapyard in 1967 fifty six year later.

Consul’s original boiler lasted for her whole operational career from 1896 until 1965. That’s sixty nine years.

Contrast that with these paddle steamers:

In an operational career of forty years Balmoral got through three boilers, the one with which she was built in 1903, a new one only seven years later in 1907 and then again a third in 1920.

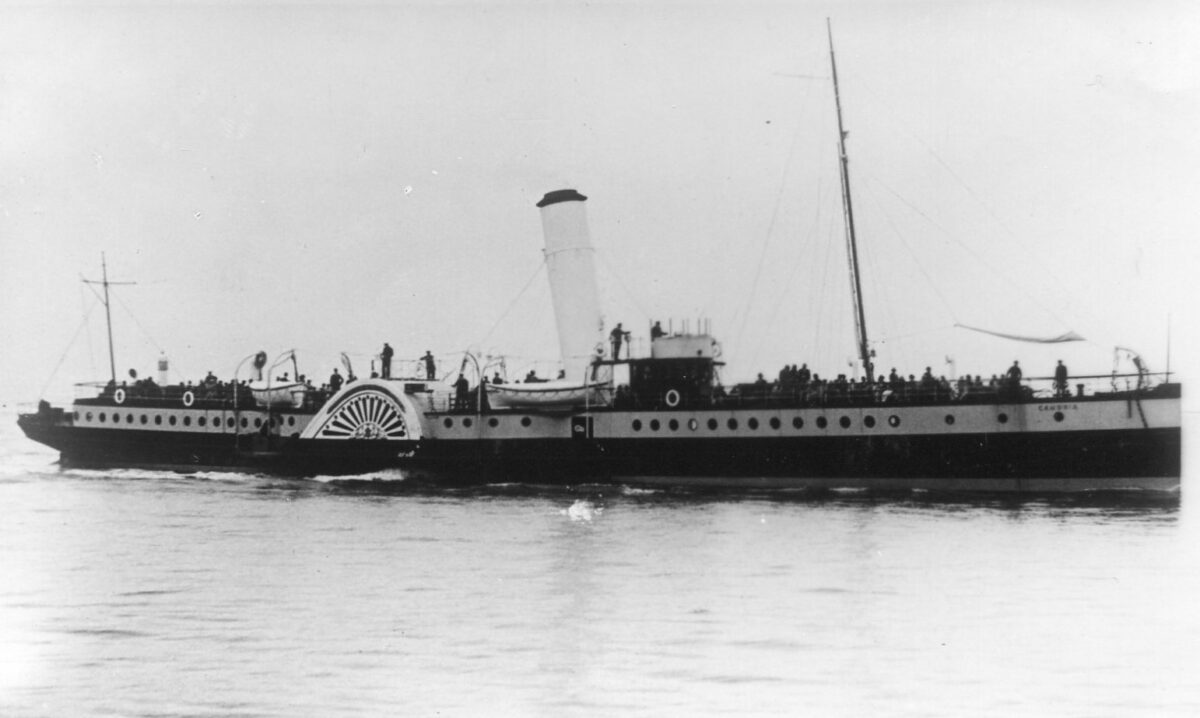

In her forty five year career P & A Campbell’s Cambria got through three, the one with which she was built in 1895, then in 1912 and again in 1935.

P & A Campbell’s Britannia had four boilers in her sixty year career, the first she was built with in 1896, then again in 1921, 1935 and in 1948. That’s four boilers in a timescale for which Consul had just one.

So why this great disparity? How come some paddle steamer boilers lasted so much longer than others?

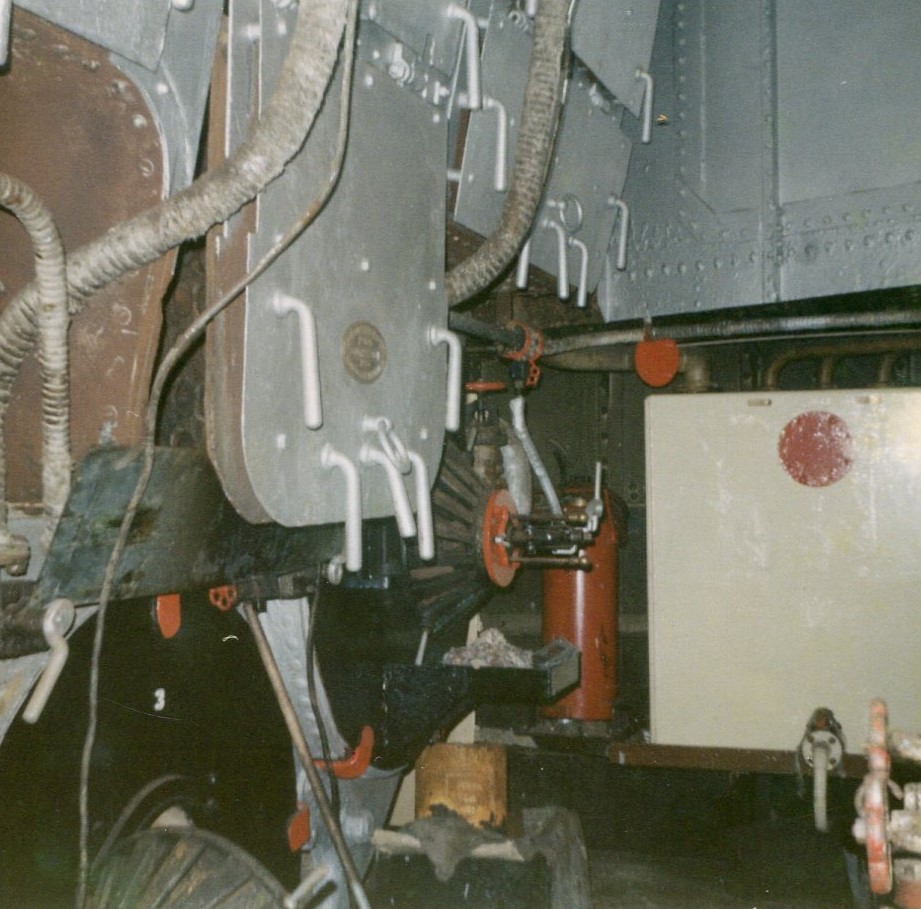

In the first place these traditional Scotch marine boilers with domed end plates were over engineered for what they were designed to do. They definitely had a capacity to live on, if treated well, beyond their design life in comparison with modern package boilers.

And being treated well by attentive engineers who nurtured rather than stressed a boiler would definitely have affected its longevity. For example heating up a boiler from cold slowly to give even expansion throughout the whole structure is important. If you do it too fast when a fire is first lit the top of the boiler may become very hot indeed fairly quickly whilst the bottom is still stone cold inducing unwelcome stresses and strains within the boiler structure as a whole. Boilers don’t like that.

Over aggressive firing maybe causing hot spots would not have helped either. And different coals do burn in different ways. For many years we used Deep Navigation coal for KC from the eponymous mine in South Wales. It was as near perfect as imaginable. It burned well. Not too much smoke. Enough but not too much ash. An even sort of firing which never let you down for want of steam but also damped down nicely when you didn’t want it when you were alongside a pier. When that mine closed we tried all sorts of other coals and they were all different. One particular one burnt so fiercely that it melted the fire bars which fell into the grate. With Deep Navigation a set of firebars lasted several years. We got through four sets that season until we sourced other and less aggressive coals. And that coal was hard to damp down leading to the safety valves lifting alongside piers which is a serious issue on a ship as you don’t want to loose any of the boiler water as it may be hard to replace if you are away from your usual boiler water top up points.

Of course notwithstanding all this all these traditional boilers would almost certainly have needed some repairs of one sort or another along the way during their lives to keep them going. That is in the nature of the beast. It is common for such boilers to develop tiny cracks. That is normal. They need repairing and this is most often done by grinding them out and buttering them up with new weld which is then buffed off. So there will have been a lot of that going on to keep the boilers in service and extend their careers.

Boilers also prefer a nice steady water level and can easily be damaged if the water is too low which increases the risk of exposing the heating surfaces, including the furnace crown and the boiler tubes. That is very bad indeed for a boiler. That is why to minimise this risk traditional marine boilers were ever designed with a greater height between the top of boiler tubes and the underside of the top of the boiler than on land based plants to try to maximise the amount of water in the boiler and thereby minimise the possibility of this unwelcome side effect when the weather was poor, the wind fresh, the sea rough and there was lots of roly-poly slurping the water backwards and forwards and up and down within the boiler.

It can’t be just by chance that paddle steamers sailing on exposed routes tearing along flat our to keep to the timetable on very long days got through boilers faster than those with easier schedules on more generally placid and less stressful routes.

Balmoral spent much of her career sailing on very long day excursions from Southampton and Bournemouth across the Channel to Cherbourg as did Cambria at the start of her career before subsequently becoming best known for her speed on P & A Campbell’s down Channel routes to Ilfracombe. P & A Campbell’s Britannia spent most of her career on the very long flagship route connecting Bristol with Ilfracombe. These were days with early starts and very late finishes with the need to push the steamers on through sometimes very poor weather to get the passengers home and with little opportunity to top up boiler water along the way.

It can get pretty rough on the Bristol Channel with the swell rolling in from the Atlantic and it can get pretty rough crossing from the South Coast to France. There can be a lot of roly-poly in which the water slurps around inside a boiler and, in extreme cases particularly if the level in the gauge glasses is getting low by the end of a very long day, the heating surfaces, the top of the furnace crown and the tops of the boiler tubes run the risk of becoming exposed momentarily but over and over again as the ship pitches and rolls shaking about the water inside the boiler. This does a boiler no good at all.

Take as an example that you go out in the morning on Balmoral from Bournemouth to Cherbourg and it is not too bad. It is windy but not windy enough for you to cancel the trip. The forecast suggests that the wind may moderate later. By teatime when you are due to set off for the return from Cherbourg it is a different story. The wind has not yet moderated but has risen. It really is too windy to sail but you need to get your passengers back and you hope that it will moderate in due course as it was forecast to do. But it doesn’t. It gets worse and having set off the more you go on the worse it gets over the several hours it takes to get back across the Channel. Halfway there is an issue with the boiler feed pump as there sometimes is. This isn’t at first noticed. Then it is spotted when the water in the gauge glasses starts to get visibly lower. You bleed the pump so it starts to function again but you have lost quite a bit of feed water in the interim. You pump what you have in spare fresh water from the reserve feed tank into the boiler. You look at the gauge glasses. You see the level hovering just in sight in one glass when the ship rolls one way and then just in sight in the other when she rolls the other way. You wonder if it is enough to get you back before you have to take the nuclear option and open the valve to put seawater in the boiler. You don’t want to do that. Salty seawater is not good for a boiler but all traditional marine boilers had the ability to put some in as necessary as doing that is preferable to running out of steam disabling the ship with a strong tide setting you down towards a rocky headland in a serious blow. You may have damaged the boiler but you have saved the ship.

Contrast that with Shieldhall. She has spent her career first on the Clyde and then based at Southampton with only minimal exposure to the worst sort of seagoing hurly burly and never in the extreme. Nice flat trips to drop her cargo of sewage first on the Clyde just sticking her nose out beyond the Cumbraes and then from Southampton doing the same thing in the lee of the Isle of Wight. And these days although she has to go to Falmouth for drydocking there is a weather restriction on that and all her commercial sailings are within the Solent plus a quiet run across Poole Bay when the weather is fine. Generally speaking she has had a career with not very much roly-poly and certainly no serious roly-ploy. Ever. Nice flat water level in the boilers.

Today seventy years on she still has the same boilers with which she was built in 1955. In that same timescale Britannia running flat out and tossing and turning on the sometimes extreme hurly burly of the Bristol Channel got through four.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran