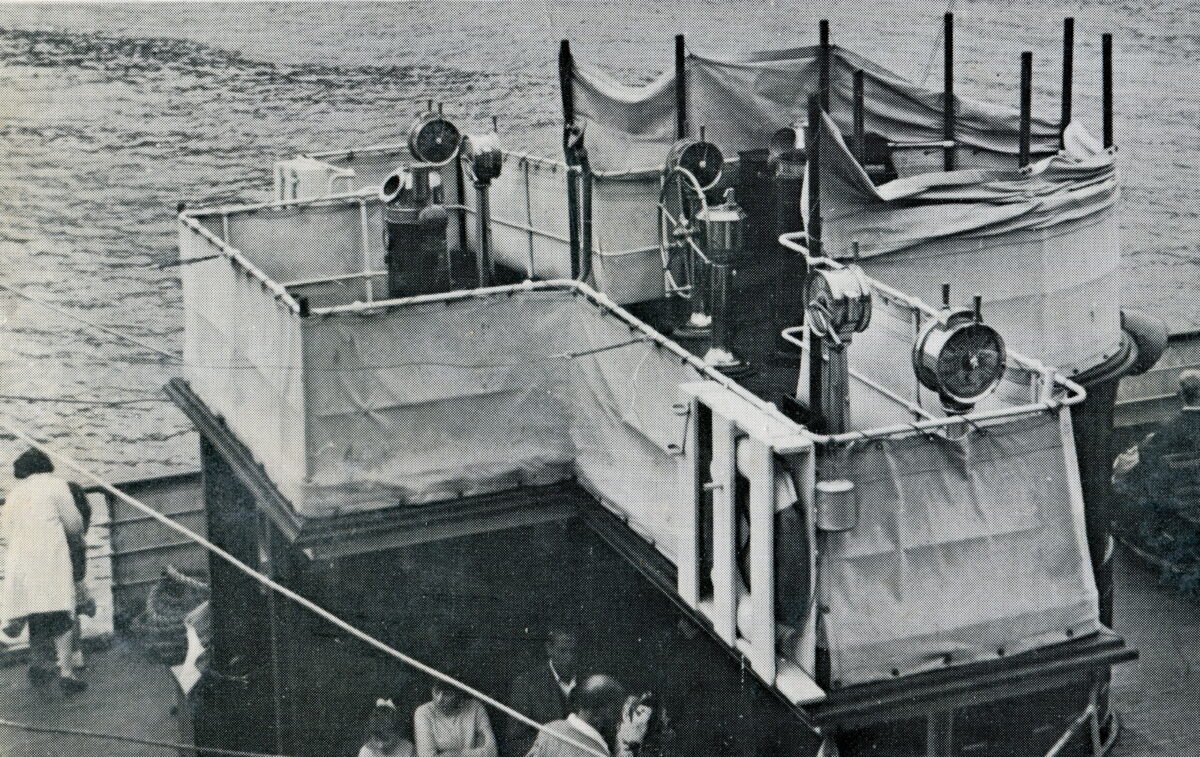

Compared with ships today there is not a lot of kit on the bridge of P & A Campbell’s Glen Usk (pictured above): an engine room and docking telegraph on each bridge wing plus another engine room one in the middle, two binnacles, a polished brass wheel with mechanical rudder indicator, a chart table, a box for things like binoculars and a voice pipe to the engine room. That is about it. No electronic navigational aids and definitely no bookcases stuffed full with a plethora of Safety Management and Permit to Work files. Yet these excursion paddle steamers with their very basic kit and traditional navigational skills enjoyed a superb safety record particularly when compared with modern roll-on/roll-off ferries, four of which have capsized and sunk in European waters with considerable loss of life in the last twenty or so years. Inevitably there were the occasional paddle steamer accidents, collisions and strandings. But these were rare amongst the very large number of steamers sailing around our coasts from the middle of the nineteenth century up to the 1960s.

Of course, all the new electronic navigational equipment has brought huge benefits. Radar shows you where you are and, in theory, all that is around you. GPS gives your position with an accuracy way beyond traditional dead reckoning. Echo sounders give the depth under you. And, most recently, AIS has arrived to provide a mass of helpful information about other vessels in your vicinity, including their names, where they are going, their speed, course over the ground and much more. There is no question that the paddle steamer captains of the past would have welcomed this wonderful technology with open arms.

However, life being what it is, for every benefit there is a down side. Today a ship’s bridge may be better equipped than in the past but that equipment needs protecting from the harsh salty marine environment. This means that most bridges today are now fully enclosed. This puts the lookout behind glass, divorced from the elements, in a comfortable air conditioned environment with the soothing lull of the glow of the background lights from all the various screens around him and the comforting knowledge that spotting what is out there is not just down to him. There are lots of electronic eyes as well. However conscientious a lookout may be, his job today is not quite the same as it would have been peering out into the gloom from the windswept open bridge of the Glen Usk.

Then there is the kit. However well equipped a bridge may be with every bang up to date piece of high-tech equipment known to man, what happens if that kit doesn’t show you everything out there despite its sophistication? The MAIB have just published a report into the loss of the yacht Ouzo which was either in collision with or was swamped by the large roll-on/roll-off ferry Pride of Bilbao to the south east of the Isle of Wight on a fine night in August last year. It makes scary reading for any who go to sea in yachts at night.

Exactly what happened aboard the Ouzo must be conjecture as none of the three highly experienced crew survived. It is hard to believe that they would not have noticed the Pride of Bilbao steaming in their direction with all her passenger accommodation lights twinkling brightly. It is likely that they expected the ship to pass them by. What they could not have known was that the Pride of Bilbao was approaching one of the waypoints in her pre-arranged passage plan at which she was scheduled to alter course to starboard for the next leg of her voyage down the Channel. As she got closer and closer, the yacht crew may have noticed that the ship had started to turn slowly towards them. They may have thought that they had been seen and that the larger ship was altering course to go round their stern. They could not have known that they had not been seen and that the Pride was simply coming round onto a new heading, a heading straight for them.

On the bridge of the ship, the highly experienced Second Officer was in charge of the watch, assisted by a highly experienced AB as lookout. The AB had just come up from the accommodation so it is thought that his eyes may not have had time to adjust to the night outside. To make matters worse, there was considerable background light in the wheelhouse from the ship’s decks and most particularly from the many instruments and the chart table. To make matters even worse the lookout’s glasses were the modern state of the art sort with photo-chromic lenses which turn themselves into sunglasses when it is bright and lighten up when it is dark. Both men were physically fit and in possession of the appropriate ENG1 medical certificates. After the incident the AB’s eyesight was tested again and found to be absolutely fine.

It is known that the lenses of yacht navigation lights are subject to crazing which may reduce their luminous intensity and hence visibility. The lookout on the Pride did spot the yacht’s lights but not until they were very close. He informed the second mate who initially thought that he must be referring to lights at some distance as nothing had been showing on the ship’s radar anywhere in the vicinity. The ferry’s black box recorder confirms this. A more urgent prompting from the lookout brought the second mate from the chartroom and he promptly took avoiding action. Both men looked astern, saw a light and believed that they had missed the yacht and that it was safe. With the sunny glow of hindsight this was an error of judgement. The yacht was not safe. It had either been hit or swamped. It was never recovered. The bodies of the three crew members were found in the water within the next two days.

The report is critical of the second mate for not taking more steps to check that the yacht was safe afterwards by trying to call it on the radio or by stopping the ship to search although it also states that a psychologist who was consulted afterwards thought that the second mate’s belief that the yacht was safe after seeing the lights astern would be a pretty normal reaction in these circumstances. The report also says that that the captain should have been called to provide another set of eyes and a second opinion. This year being 2007 the police have become involved and the second mate is to be sent for trial for manslaughter at Winchester Crown Court in October.

The MAIB makes various recommendations. A lookout’s eyes should be given time to adjust to the night before he takes over. Photo-chromic glasses should not be worn. Good blackout procedures on the bridge should be used. Yachtsmen should check their navigation lights are on and should check that they are are good condition. And if yachtsmen have any reason to believe that they have not been seen by a ship they should take all steps to make their presence known including calling on the radio, shining lights on their sails or at the ship’s bridge or by setting off flares.

Perhaps the thing which will be most startling for most people is that the yacht simply did not show up on the Pride of Bilbao’s radar even though it is believed that the yacht was fitted with a radar reflector. The problem here is one of so called clutter from waves. Radars are so good that they will pick up reflections from anything and that includes waves if there is a bit of a sea running. These confuse the pattern on the screen making it look as though the ship is surrounded by objects when in fact it is only surrounded by waves. To solve this, radars have a clutter knob which can be turned to remove the effect of the waves from the screen. As a very modern radar, the Pride of Bilbao’s also had an automatic clutter remover so that it routinely airbrushed out from the screen waves and anything the size of waves in the vicinity. And that meant yachts as well.

I am not in any way arguing against modern electronic technology. It is a real boon for mariners. But it is not everything. And I cannot help but feel that this particular sort of accident would have been rather less likely to have happened in the heyday of excursion paddle steamers like the Balmoral (pictured above off the Isle of Wight) despite the absence of sophisticated electronic equipment and Safety Management files on their bridges. I think that if I was out at sea on a yacht at night I would rest easier in my mind seeing a traditional paddle steamer heading towards me with the knowledge that her lookout would be out there in the open with his eyes accustomed to the dark, rather than seeing a modern roll-on/roll-off ferry on a collision course with me with her lookout behind glass, in a comfortable air-conditioned environment with a poor blackout and the soothing lull of the glow of the background lights from the various screens around him that failed to show that I was there at all.

Read the full MAIB report here.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran