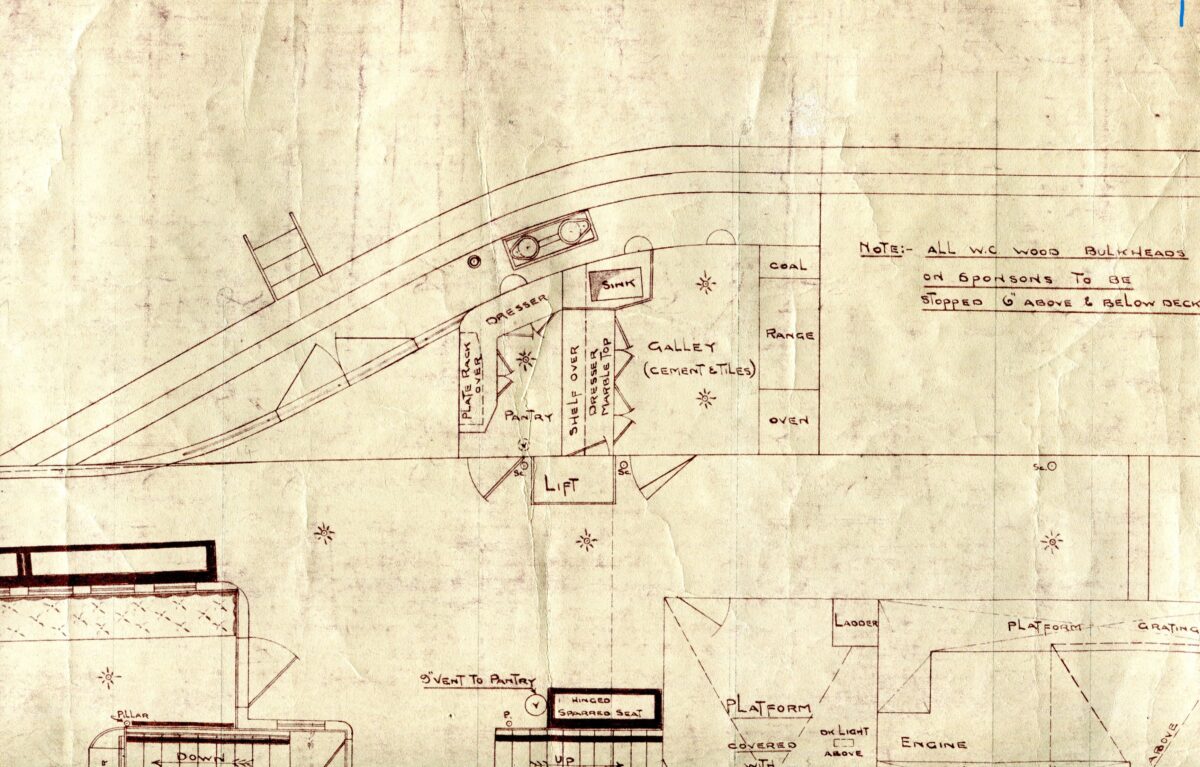

Embassy had her galley positioned on the port side sponson abaft the paddle box. The porthole closest to the camera in this picture was for the pantry which contained a dresser, plate racks and shelves. The other two portholes forward of that were in the galley itself which contained a coal fired range, an oven, a sink, a bunker for the coal for the range and various shelves.

From the General Arrangement plan I have here with me the footprint of the galley was about 6ft x 8ft. The deck was tiles on cement. There was a small skylight above to provide extra light and some ventilation with the smoke from the range was taken up through an H topped chimney. This H top was a cunning wheeze to help provide an extra draught through the range. Hot air rises. The smoke went up and was then diverted left and right before going up again through each of the two escapes. These were tubes with holes in the bottom of them through which air was drawn as the smoke rose thereby providing an extra draught to push the smoke upwards and consequently draw more air into the galley range below.

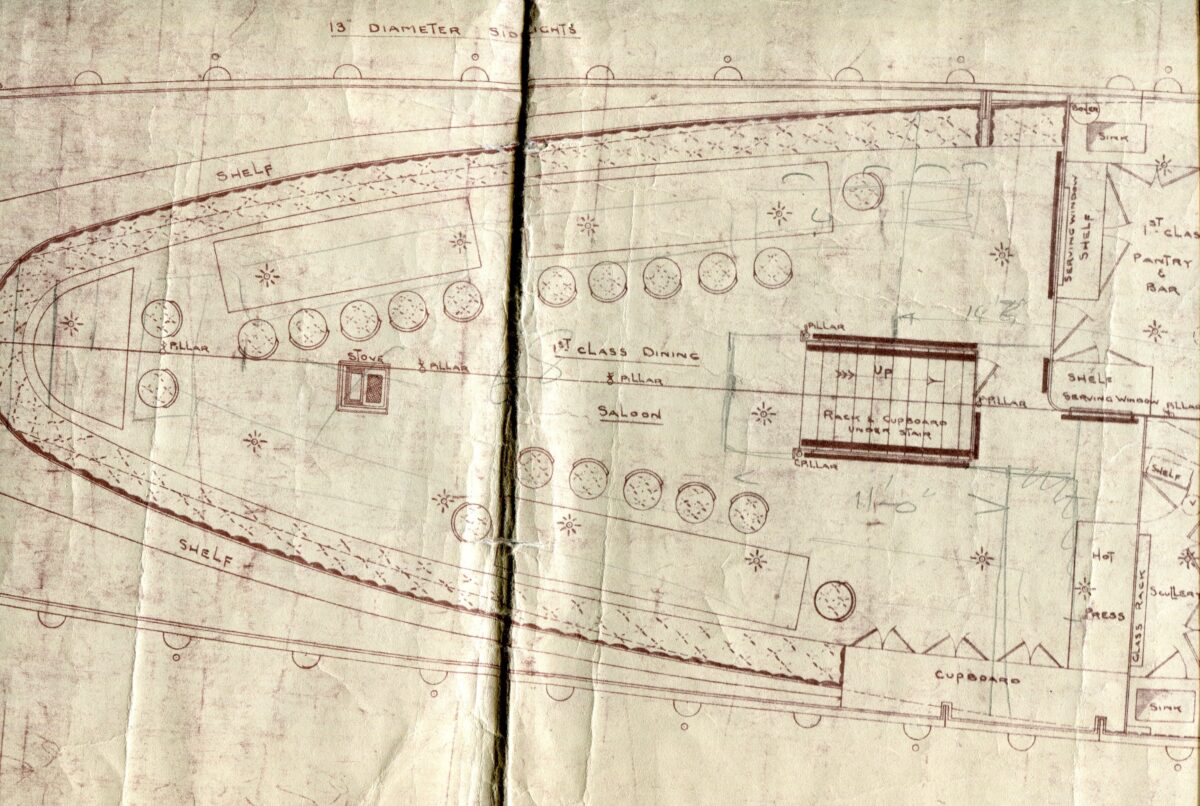

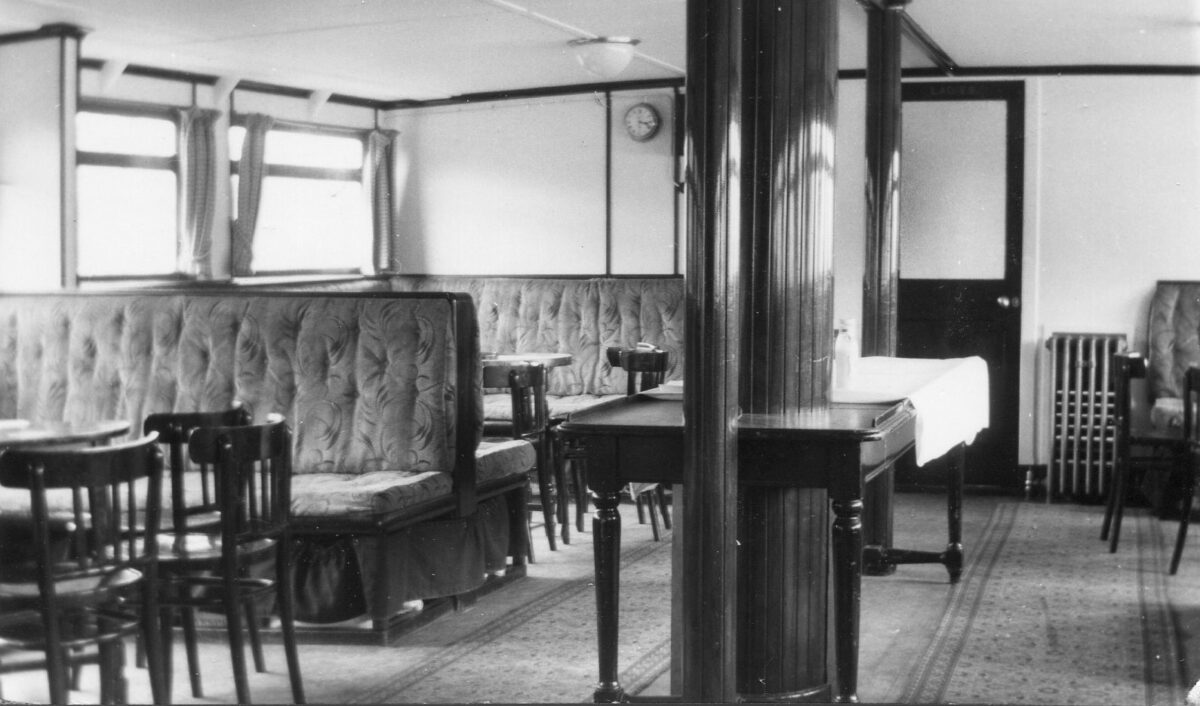

When I first sailed on Embassy in 1960 the steamer notice for her and Monarch’s sailings from Bournemouth declared “The steamers are equipped with large, well appointed dining saloons where meals and refreshments may be obtained.” That was true up to a point although of course large is a relative term. Large in relation to what? In truth the dining saloons on both Embassy and Monarch were of fairly modest dimensions occupying the space between bulkheads on the lower deck aft.

The General Arrangement plan shows that the dining saloon was 48ft long, 24ft wide at the forward end, 18ft wide at its mid point tapering down to just 6ft wide at the aft end. On the port side at the forward end was a pantry/bar which contained a sink, lots of shelves and a dumb waiter up to the main deck level just outside the galley. On the starboard side forward and entered through the pantry/bar was a scullery which contained a sink with a Windermere kettle on the outboard side and a large dresser/cupboard along the bulkhead with plate racks above it and a glass rack on the right hand side as you went in. At the forward end and on the starboard side of the dining salon itself was another large cupboard and a hot press. In the main body of the dining saloon there were two long tables for diners on the port side and one on the starboard side with seating around them for eleven, ten and twelve respectively. Squashed into the narrowest part of the aft end of the saloon was another small table which could accommodate six around it. So that is a total seated capacity of thirty nine diners on a ship which had Passenger Certificates for more than seven hundred. Even with two sittings for lunch that meant that Embassy could feed less than 10% of her passenger capacity for a full meal. If the other 90%+ had wanted a meal then sorry it just wasn’t doable.

And that was generally fine. In those days not many passengers wanted to buy a full sit down meal. And for those who did the food was simple including, for example, ham, egg and chips. That is the sort of meal for which the ingredients are easy to store in bulk. They are easy to prepare. One of them is served cold anyway and cooking eggs and chips requires only low end culinary skills so long as the fat is hot enough.

The schedules also mitigated against passengers wishing to eat aboard. There was the Swanage service at forty five minutes each way. Well there isn’t really time to have a meal on that sort of trip and in any case there were plenty of eateries if people wanted in both Swanage and Bournemouth. And there was the double run, one in the morning and one on the afternoon, from Bournemouth to the Isle of Wight taking an hour and a half each way. Again not much call for meals on trips like that with the passengers in any case looking forward to time ashore at Totland Bay or Yarmouth.

By then the long day trips to Southampton, Portsmouth, Weymouth and Round the Isle of Wight, on which there would have been a higher demand for dinners with the passengers trapped aboard all day, had generally been abandoned. They had involved a lot of steaming. They burnt a lot of fuel and cost a lot in wages. They had drawn an ever diminishing passenger payload. Contrast that with Embassy’s day trip to Totland Bay or Yarmouth, Isle of Wight from Bournemouth for which day trip fares could be charged but which only involved steaming one and a half hours each way. In the peak weeks these were often packed to capacity with punters right up to Embassy’s last season in 1966. That’s the way to do it. High fare per hour steamed. High volume of passengers. Low operating cost. Kerching.

Consul had two mini-galleys each equipped with their own small range one each side on the sponsons abaft her paddle boxes. In this lovely picture of her alongside Bournemouth Pier in the early 1950s you can see her two H topped galley chimneys one port, one starboard. Her dining saloon capacity was even smaller than that on Embassy and Monarch with about a quarter of its footprint on the main deck aft given over to the Ladies lavatory concealed in this picture behind the white painted windows.

However by this stage in her career Consul did not offer meals. Her steamer notices for 1960 declared “Teas and light refreshments served aboard”. No mention of any hot sit down grub.

The same was also true on Princess Elizabeth in her final years operating under new management in the 1960s. She lost her dining saloon on the lower deck aft before the 1960 season when the Board of Trade insisted that an additional bulkhead be fitted across the middle of it in order for her to regain her Class III Passenger Certificates which she had lost in the early 1950s. She did not serve meals after that. Her subsequent steamer notices declared “Refreshments, teas, beers, wines and spirits etc served at popular prices on all cruises”. Again no mention of any sit down full meal type grub.

And this reflects the very real challenges and costs of serving full meals on paddle steamers with limited dining saloon capacity in relation to their Passenger Certificate, with limited storage space for fresh and quality ingredients and with galley space and equipment on the low side compared with your average transport cafe. Think of the size of the Embassy’s galley at 6ft x 8ft. Not very big is it? Try getting 700 dinners out of that and see how far you get.

Of course serving quality food to a high standard can be done. And it can be done well. Liners serve food varying from the cheap and cheerful to high end all the time. But they have sufficient space. They have sufficient quality staff. They have sufficient kit in sufficiently large kitchens. They have sufficient tables and chairs for all. They have sufficient space to accommodate all the staff overnight in cabins. And they know in advance every day how many covers they will need to serve.

The Swiss generally do it too on their paddle steamers. On most trips for most of the time they usually have sufficient seating for all who wish to eat having fitted large glass saloons on the promenade decks of their paddle steamers for the overflow from their dining saloons to cope with today’s demands. They have a shore based catering backup on each lake to provide the food and drink. There are often top ups several times a day by van to the piers at Lucerne, Lausanne, Geneva and so on. And much of the prep and initial cooking of the fine dinners is done ashore in advance and brought down. They couldn’t do it to the standard which they do achieve without all that. And that all costs. Buying lunch or dinner on a Swiss paddle steamer is an expensive business which will set you back between £25 and £65 per head according to the menu you choose. And that is not including wine or any other drinks.

Even so, sometimes it doesn’t quite work out like that. There have been a number of occasions over the years when I have travelled on paddle steamers on Lakes Lucerne and Geneva at very busy times when the steamers have been full or nearly full and all the tables and chairs for dining have been occupied. No chance of obtaining any food on these occasions if you can’t find a table. And given that their operation is tailored to table service I found it near impossible to buy a coffee or a beer either from the hard pressed waiters and waitresses doing their best to cope with the demand from passengers who had found a table. That is is not a criticism. It is just a recognition that when paddle steamers serving food are pressed beyond the capacity which they are able to deliver then that is what happens. It is sort of baked into that business model howsoever it is organised.

I think that this picture of Embassy is so atmospheric and gives such a real flavour of what it was like to be on Bournemouth Pier for the 10am departure to either Totland Bay or Yarmouth, Isle of Wight on a sunny and calm August morning in 1964. Goodness what a lot of passengers there are just climbed aboard. Many are thronging around the starboard side where the folding deckchairs were handed out from under a green tarpaulin on top of the paddle box. And there are AB Ted Edwards (left) and bosun Sandy Rashleigh (right) with the peaked cap doing the handing out. The deckchairs were fine when the weather was dry. But after a wet spell they tended to be a bit damp and ever had that musty smell of wet tarpaulin about them. By the gangway are mate Eric Plater and purser Frank Holloway who walked round the decks selling tickets without the benefit of a ticket bag but with the tickets jammed in one pocket and the money in the other of his uniform jacket. Ever mindful of keeping Embassy running to time Eric habitually chivvied the passengers on with his incessant cry of “Hurry along at the gangway please”. There ahead of Embassy one of the Bolson Fairmile launches, Swanage Belle, is berthing in readiness for her first trip of the day to Swanage at 10.45am. Judging by her angle I think that the tide was running in an easterly direction setting her off from the pier and making her approach into the tight corner just ahead of Embassy all the harder. On Embassy’s bridge Captain John Iliffe is looking and watching and is doubtless relieved that he hadn’t had to get Embassy into an awkward corner like that. Then there are all the fishermen on the pier with their lines drawn in doubtless getting impatient whilst Embassy interrupts the course of their day’s fishing. Star of the show it always seems to me in this picture and drawing the eye in, is the small man standing on his own leaning on the aft sponson gates at main deck level. Is he a small man? Or is he a child? Hard to say. And what a contrast his solitary presence makes standing there alone to the deck above which is just heaving with humanity.

Look closely at this picture and you will see that the galley range chimney featured in the picture at the top has now gone. In the winter of 1963/64 the coal fired range was removed from Embassy’s galley and was replaced by a gas cooker intended largely for providing meals for the crew. Although there was no obvious change aboard the ship, with the bar still open as usual, mention of catering disappeared from the Bournemouth steamer notices in 1964 replaced by the bald statement “All vessels are fully licenced”. For Embassy’s last two seasons in 1965 and 1966 “Snacks and light refreshments always available” was added to the copy. Note “Snacks and light refreshments”. No mention now of any “meals”. Cosens knew their markets. They knew what worked and what didn’t work for them. They knew what they could deliver and what they could not deliver.

I can remember going down into that dining saloon on the lower deck aft to have a look from time to time in these latter days of Embassy’s career. I remember it being rather dark. I remember it being quite empty. I don’t remember ever seeing any passengers eating in it. But I do remember seeing Captain Iliffe and Chief Engineer Alf Pover as its only two occupants sitting opposite each other at one of the long tables on the port side taking their lunch cooked on the new gas stove in the galley above on the way back to Bournemouth from Totland Bay one lunch time in August 1964. Captain Iliffe knew who I was as I was aboard often and dawdled around the Weymouth Backwater on my way to and from school on a daily basis each winter just gawping. He always acknowledged me with a smile although, unlike Captain Defrates, he never invited me up onto the bridge. Happy days in a world where my then thirteen year old self thought that Embassy would go on for ever whether or not she continued to serve any dinners..

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran