Lewis and Celia Wood were inveterate travellers on ocean liners and coastal passenger vessels. In 1949 they made two trips down the Thames, the first being aboard Royal Daffodil on Monday 11th July.

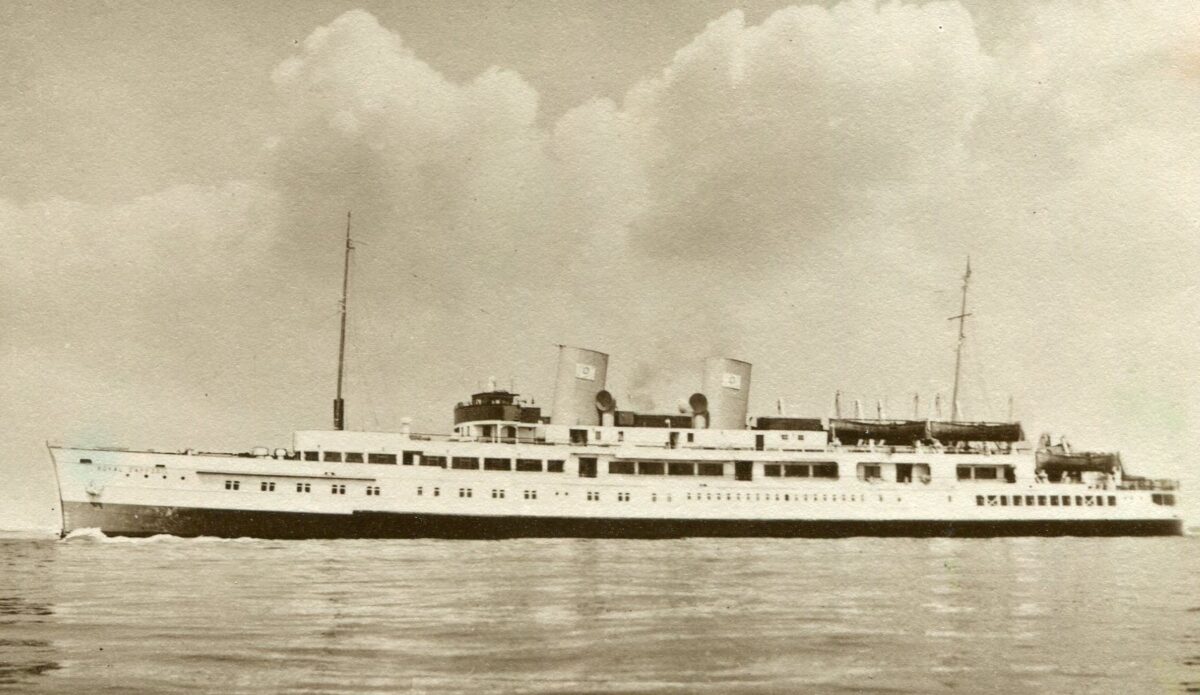

Built in 1939 by Denny on the Clyde for the cross Channel excursion trade from the Thames to Calais, Boulogne and Ostend, Royal Daffodil saw barely a full season’s service before the outbreak of war after which she was commandeered in September to evacuate 4,000 women and children from London to Lowestoft. Then it was off to Southampton to carry part of the British Expeditionary Force across the Channel to Cherbourg before being transferred to the Fleet Air Arm in 1940.

All the companies whose ships were taken up for war service were proud of their record and where the ships returned to their usual services after the war their owners wanted to tell everyone about their patriotic wartime achievements. This pink leaflet was produced for distribution aboard Royal Daffodil and elsewhere after the war. It records her service during the war including the fact that she rescued 9,500 troops from Dunkirk despite being bombed and damaged by enemy air attack and that the service of her master, officers and crew was recognised with the awards of three Distinguished Service Crosses, one Distinguished Service Medal and three Mentions in Despatches. From 1945 to January 1947 she was troop carrying between Dover and Calais and Newhaven and Dieppe before going back to her builders on the Clyde for a complete refurbishment prior to her return to peacetime passenger carrying back on the Thames.

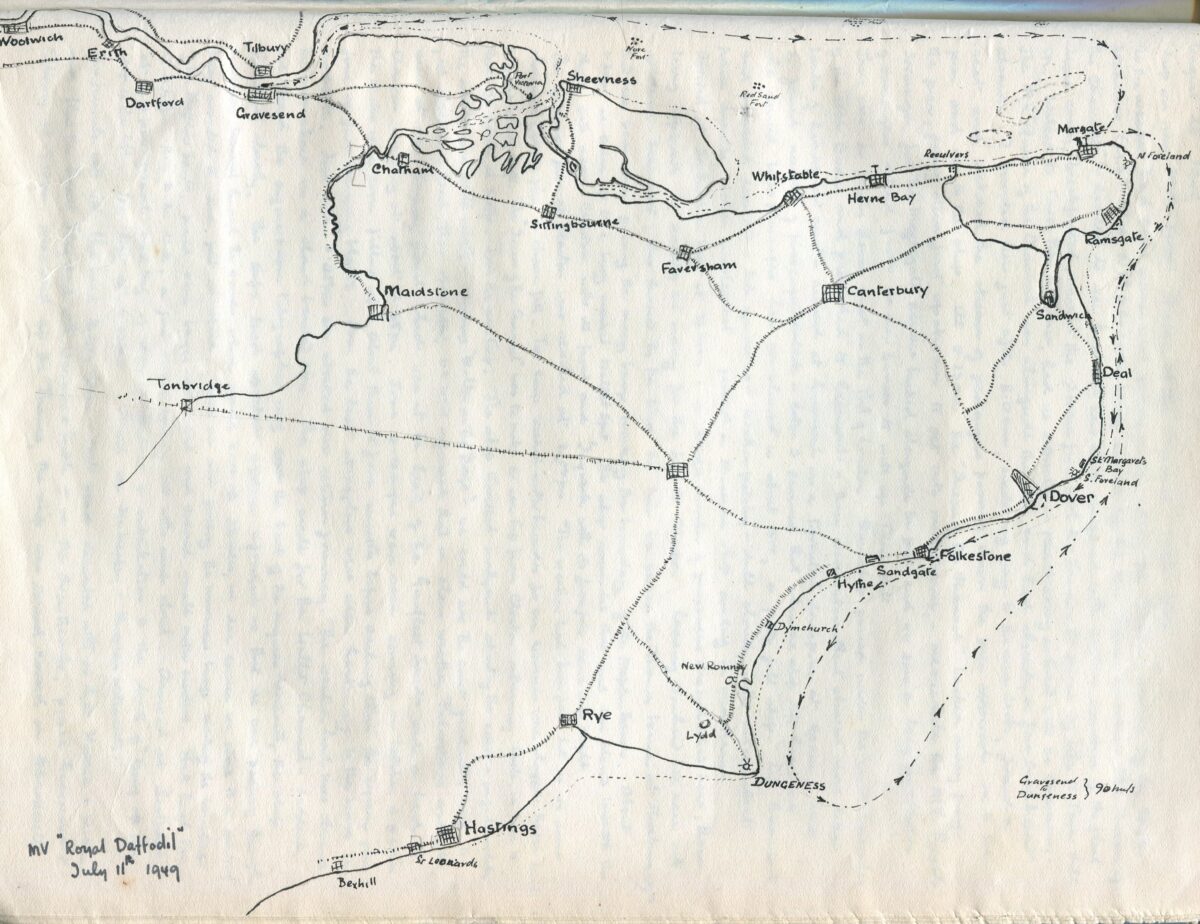

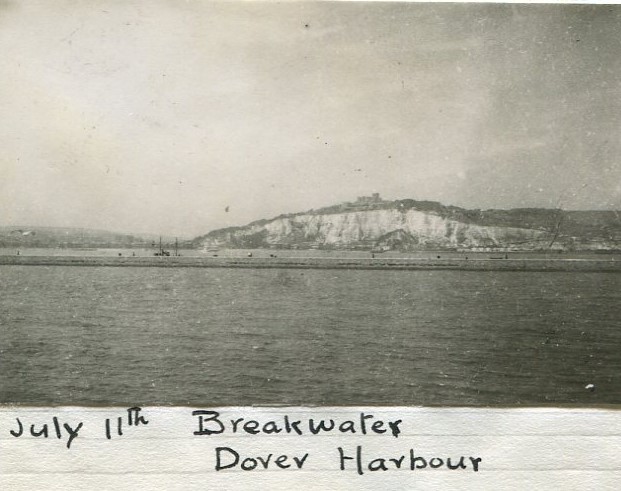

On Monday 11th July 1949 Lewis and Celia took the 8.02am train from their home in Woolwich to Gravesend, which took about 25 minutes, and crossed to join Royal Daffodil. At 9am, with a blast on her syren, she cast off, circled round and headed off down stream punching a flood tide with very few passengers aboard.

So why did she start from Gravesend? Well there was an industrial hinterland there and across to the Medway so these were market segments to be tapped. But essentially Gravesend was a useful starting point for two other main reasons. Before the war it had been the departure point for Londoners for the cross Channel trips to France or Belgium. It was just too far for the ships to sail from London to the Continent and back in a day so the London punters took the train down to Gravesend (or Southend) to join the ship there. And secondly Gravesend was a convenient overnight berth not so very far away from the major holiday resort at Southend from where good loadings were generally guaranteed at least in the peak weeks. Strood was closer, and was used by the ships of the New Medway Steam Packet Co, but Strood Pier was not suitable for vessels of this size.

Monday 11th July was cool with not much sun and the wind was in the east which is a not very nice direction on the Thames particularly when it is blowing against the ebb tide which can cause quite a short, sharp and unpleasant sea even in only moderate easterly wind conditions.

They arrived at Southend at 10.15. A few of the few passengers got off and about another five hundred swarmed aboard. Then it was off to Margate where most of the passengers went ashore and about one hundred came aboard. Not a lot really for a ship with a Passenger Certificate for 2,396.

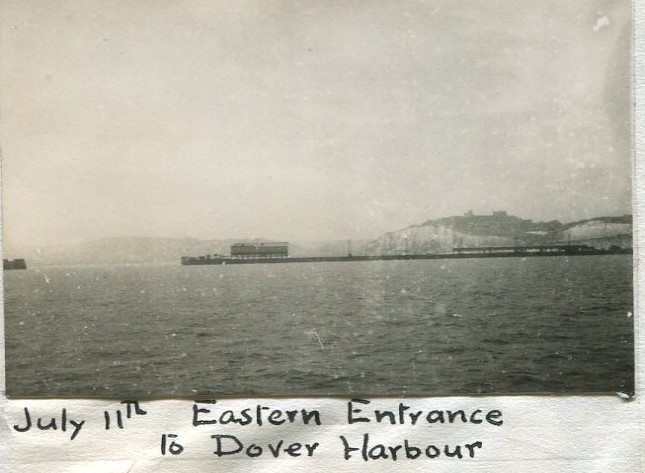

Before the war it would then have been off to France doubtless with a much better compliment wishing to “Go Foreign” but that was not possible in 1949 with the Government insisting that all travellers abroad must have valid passports. Gone until 1955 was the “no passport” option. So gone also were the trips to France. Instead cruises were offered either across the Channel to view the French Coast or, as on this day, along the Kent Coast passing, Dover, Folkestone, Hythe and on to Dungeness where they turned at about 3pm, circling around the anchored pilot cutter waiting for ships needing a pilot, and onwards returning back to Margate.

As the day wore on the sun came out and from Margate they enjoyed a “glorious run up the Thames in brilliantly sunny weather with the North Kent Coast very distinctly visible with very sharp detail”. They were at Southend 7.30pm – 7.45pm and arrived back at Gravesend at 8.55pm. They then took the 9.07pm train, changed at Dartford, arrived back at Woolwich Arsenal at 9.45pm and were home by 10pm. “A pleasant days outing” as Lewis recorded in his journal.

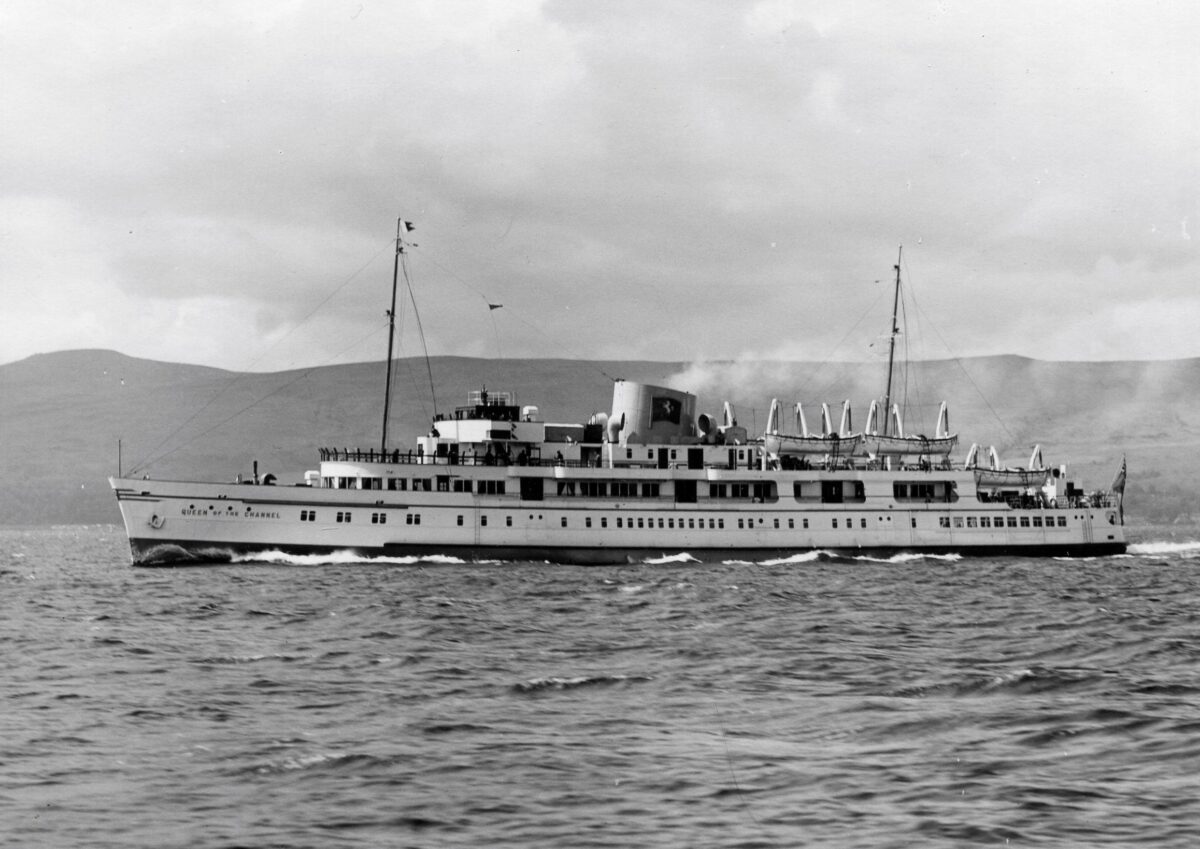

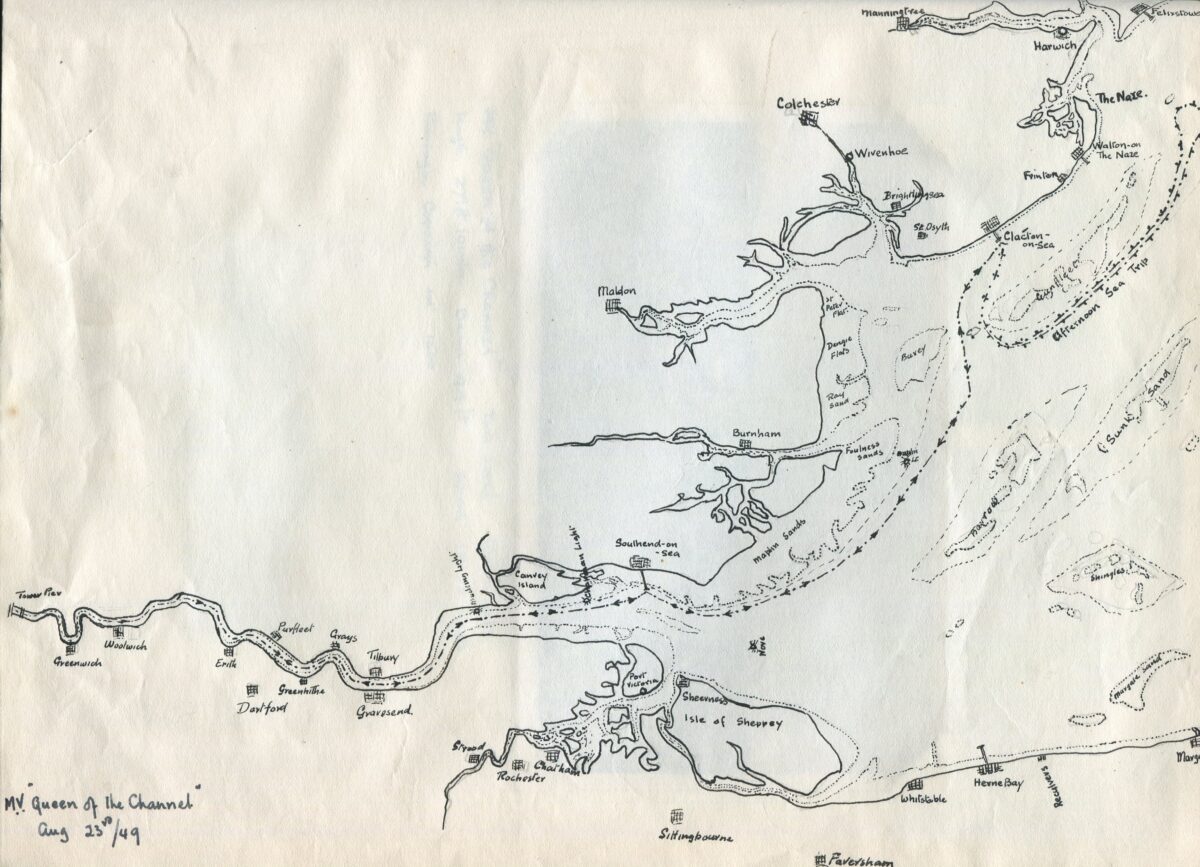

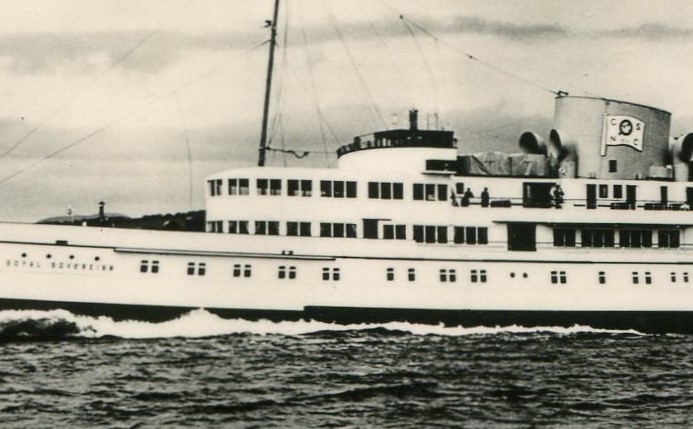

In 1949 the GSN took delivery of the brand new Queen of the Channel as replacement for her namesake dating from 1935 which had been sunk at Dunkirk in 1940. At 272ft LOA the new ship was longer than her predecessor’s 258ft LOA but she was 10ft shorter than the Royal Sovereign of 1948 and significantly smaller than Royal Daffodil of 1939 which came in at 313ft LOA. Her capacity was much smaller too with her Class II Passenger Certificate for International Voyages allowing her to carry just 1,350 passengers from the Thames and English Channel ports to the continent between Cherbourg and the Hook of Holland.

With her arrival the GSN really had too many ships for the available traffic particularly given that the cross Channel routes were off limits to them at that time. The almost brand new Royal Sovereign, which had arrived the previous season, was rostered to run from London to Southend, Margate and Ramsgate. She was shadowed by the paddle steamer Royal Eagle doing the same thing. Royal Daffodil ran from Gravesend to Southend, Margate and then on for an extended sea cruise as we have seen. And the paddle steamer Golden Eagle took the trips from London to Clacton. So what to do with the new Queen of the Channel? Initially she was based at Ramsgate but the business from there did not seem to justify the new ship. So from the middle of the season she replaced Golden Eagle taking over the service from London to Clacton. Golden Eagle was withdrawn. She never sailed again and was scrapped in 1951.

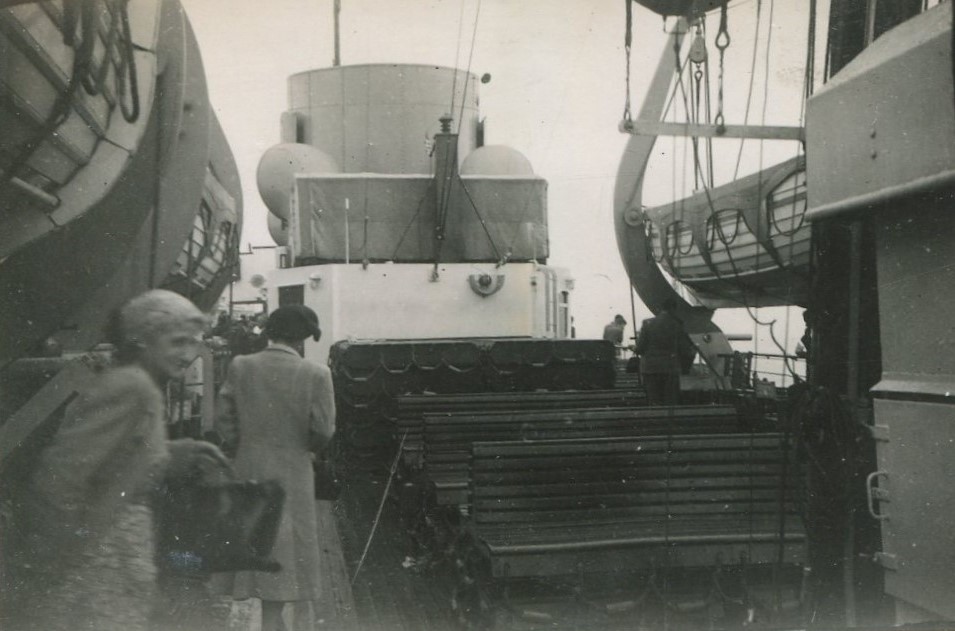

Lewis and Celia Wood noticed this. They were keen to take a trip on this brand new excursion vessel. So on Tuesday 23rd August 1949 they took the 7.14am train from Woolwich Arsenal to Cannon Street and then the tube to Tower Hill. They had no difficulty purchasing a ticket for the trip. There was no queue and they were aboard by 8am. Just after 8.20am Queen of the Channel backed off from the pier into the middle of the river to await the opening of Tower Bridge as Royal Sovereign slid into the berth they had just vacated at Tower Pier in readiness for her own day trip down river to Southend, Margate and Ramsgate.

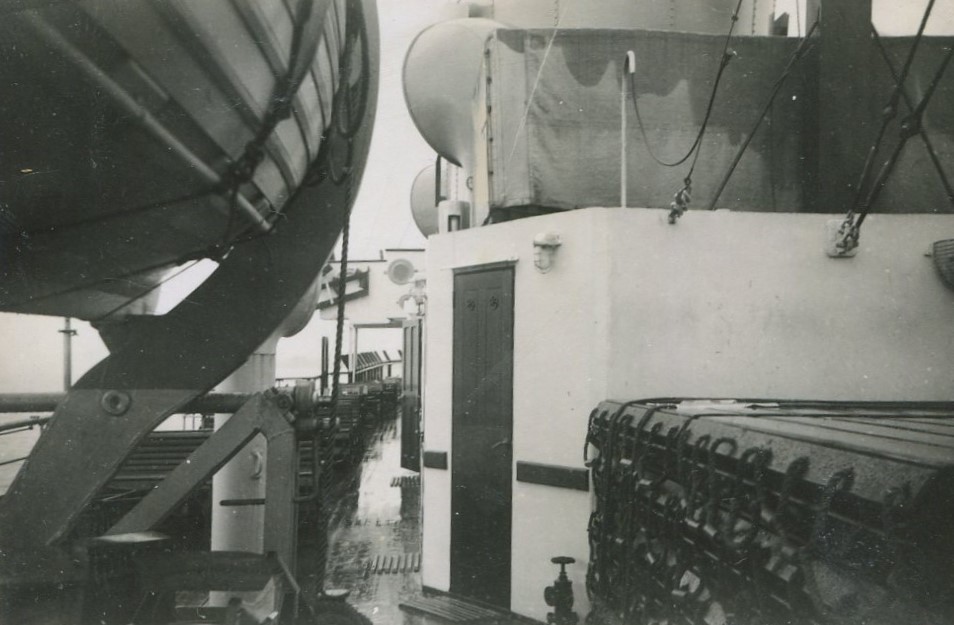

Lewis noted that it was a murky, misty morning interspersed with drizzle which accelerated into a torrential downpour just as they arrived at Greenwich at 9am. There a large number passenger boarded bringing Queen of the Channel almost up to her Class IV passenger capacity. Lewis noted in his journal “weather patchy, dull, cloudy, with intermittent rain squalls – all rather unpleasant”. They arrived at Southend at 12 noon where most of the passengers disembarked and were replaced by a similar number coming aboard for the run up the coast to Clacton.

Then it was off again in a thick sea mist with views of nothing until they reached the Wallet Spit where they slowed to cross the shallow water before speeding up for Clacton where they berthed, in another heavy rain shower, at 2pm.

They decided to stay on for the sea trip on which they saw little due to the poor visibility that afternoon. Lewis noted “We were informed over the tannoy at the turning point off the Gunfleet Sands that on a clear day we would be able to see as far as Felixstowe. No such luck today. All we could see was mist, mist and more mist”.

They were back at Clacton at 3.35pm. The captain blew the syren to encourage stragglers to get a move on and at 3.45pm they were away again to retrace the route back to Southend where they arrived at 6pm. Unloading and then loading more of such large numbers of passengers in a tight time slot was ever a difficulty. Lewis noted the shouts at the gangway “Hurry along please. Keep to the left!”

Southend was left at 6.15pm, Tilbury passed at 7.10pm and the ship turned in Blackwall Reach from where she backed up to Greenwich and berthed at 8.50pm.

Lewis noted “The promenade overlooking the pier was illuminated with numerous coloured electric lights and the rails of the grounds overlooking the landing stage were lined with spectators. Left the Queen of the Channel at 8.50pm and had a last look at her from the promenade. Caught the tram back to Woolwich and so home. A pleasant day in spite of the unpropitious weather.”

In his post trip notes he went on to say “She appeared to handle well, had the normal vibration of a motor ship but had an irritating whistle or whine which became very pronounced as soon as full power was put on at full speed. At slow speed it was not so noticeable. I understand that this is due to ventilation and air intake into the engine room.”

Tiny Point of Detail 1: Managing Director of the New Medway Steam Packet Co and major shareholder with the GSN Capt Sydney Shippick started his career with Cosens before the First World War. At the young age of 29 he was the last master of their spartan and antiquated paddle steamer Brodick Castle. He remembered the sometimes cold, wet and windswept passengers aboard her in his youth so as his own businesses on the Medway and Thames developed and thrived after the First World War, he felt himself to be on something of a mission to improve the standards of passenger comfort aboard his vessels.

It was Capt Shippick who was the driving force for the building of the large diesel excursion vessels Queen of the Channel, Royal Sovereign and Royal Daffidil in the 1930s all of which had loads of undercover accommodation. It was Captain Shippick who was at the centre of building the new Royal Sovereign and Queen of the Channel after the Second World War.

The apotheosis of all this was with the second Royal Sovereign of 1948 which not only had masses of covered accommodation in all the now usual places but also had the forward part of her sun deck enclosed too. Was that a good thing? Did it spawn universal praise? Or were there criticisms of it?

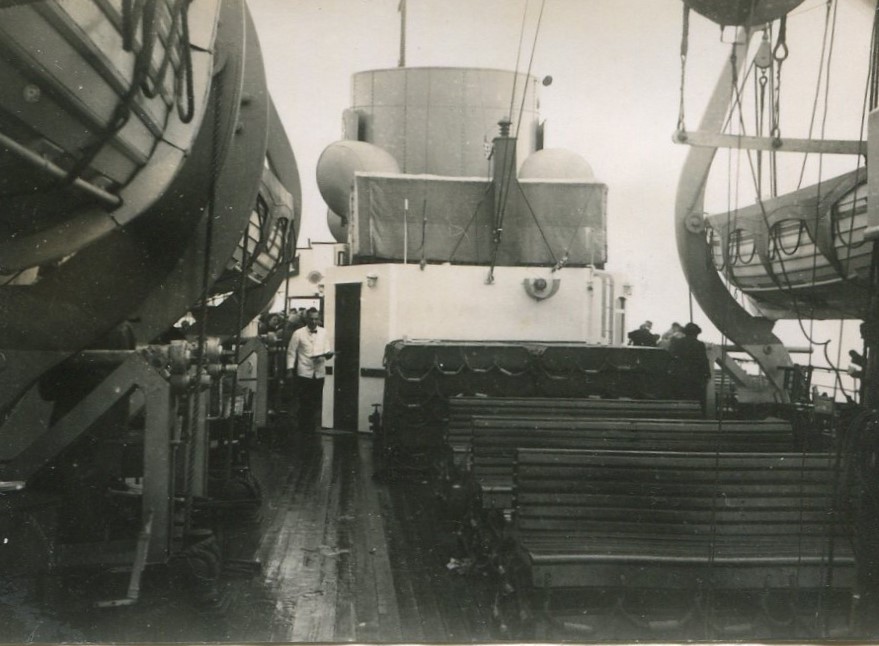

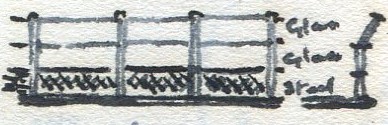

Whatever the case we know that for the second of these ships, Queen of the Channel in 1949, this idea had gone with the forward part of her sun deck left open to the elements unlike the same area on the second Royal Sovereign built just one year earlier. Were there discussions about this in the board room? Did people around the table take different views? And in the end was this a compromise? Yes we will accept no enclosure forward of the bridge on the sun deck but only on the basis that the bulwarks are one third steel and two thirds glass, that they are the height of an average passenger and have the top section bent outwards to deflect the wind and so give greater protection to the passengers.

Uncle Lewis noticed this new arrangement writing in his journal “The bulwarks around the Sun Deck forward of the bridge are in three sections, lower section vertical steel plate, second section plate glass in the same plane as the steel plate, third section same width as second of glass but slopes out at about 60 degrees to act as a wind deflector.” He even drew a picture of it.

Tiny Point of Detail 2: Capt Shippick retired around 1950 to live between houses in Bournemouth, where he had grown up, and the Rouge Bouillon, an upmarket suburb of St Helier in Jersey much associated with better off ex-pats. He was not averse to banging off letters to the local press setting out his trenchant views on Bournemouth Pier and the excursion services from it but lived on to see the total collapse nationwide of the industry which he had done so much to foster. Born on 6th October 1878 he died in Bournemouth in 1975 aged 97.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran