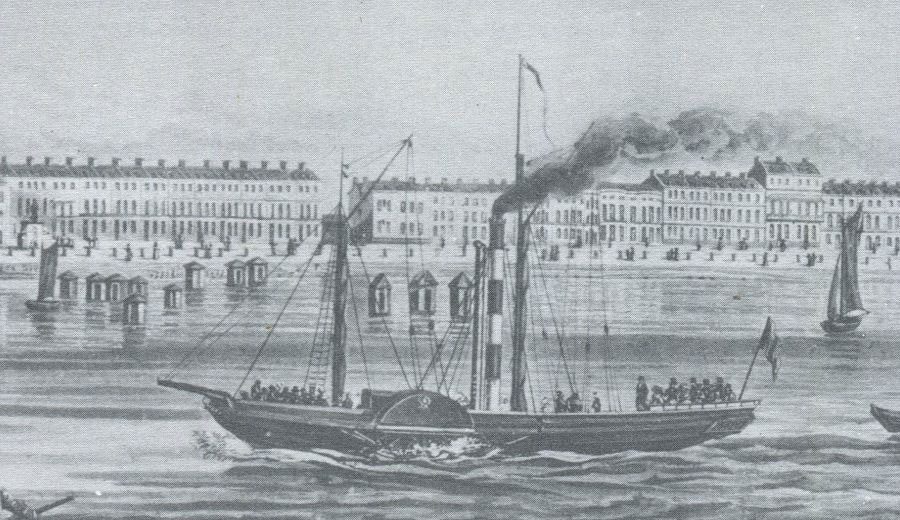

On 9th February 1836 the Jersey Argus printed a letter from a passenger recounting his recent experience of sailing on the steam packet paddle steamer Flamer on a voyage between Guernsey and Weymouth in a gale:

When we left Guernsey the wind was favourable, but in about two hours a sudden calm came on which was speedily followed by a white squall, the forerunner of a tremendous gale. About 4 pm we shipped a heavy sea which knocked in the larboard paddle box and sent the ship’s bulwarks on that side and one of the boats adrift. The mate, Roberts, had his collar bone put out. I do not know what we should have done without Captain Symonds, who gave orders with great spirit. At 11 o’clock we shipped another heavy sea which filled the places forward, as well as the boat on the booms, in the bottom of which they had to make a hole to let the water out, and we were thus left quite unprovided with boats. The Captain found he could not reach Weymouth and took us to the Isle of Wight. We were very near landing at Lymington but finally reached this place (Weymouth) at two o’clock this day (Wednesday). Had we been a few hours longer we would have been out of coals. Neither the mail or stage coaches have come in yet as it has snowed more in the last two days than it has in the last six years.

This illustrates the lack of quality weather forecasting at the time as no responsible and experienced master would have set off on a cross Channel voyage on a ship of that size if he had believed that he would be caught out in a gale.

Today a captain has a plethora of information on which to base his decisions about sailing or not sailing on account of the weather not only from mainstream sources like the Met Office but also from websites which give predictions of the force and direction of the wind, as well as the predicted wave heights, on an hour by hour basis for any particular location

In 1836 of course there was none of this with even weather maps as we know them today, with isobars and so on, still being way in the future There were storm signal stations around the coast which hoisted a cone by day and three red lights in a triangular shape by night if a gale was thought to be in the offing with the point facing upwards if the wind was from the north and downwards if from the south. However the information on which that was based was a bit hit and miss, was dependent on opinion and folklore rather than absolute fact and you had to be close enough to land to see the signal stations anyway.

The arrival of the electric telegraph in the late 1830s enabled information to be more readily gathered and distributed from distant locations which gave a better picture of the weather already in another place but heading your way on the wind.

The adoption of the term fronts did not come in until after the First World War when the similarity between cold and warm areas of pressure battling it out and military confrontations in war lent the name fronts to them.

Signal stations were placed on the Channel Islands in the early 18th Century so there would have been information available to Flamer’s master but how accurate it was I don’t know. Indeed looking south west from the Channel Islands into the prevailing SW winds rolling in from the Atlantic, or indeed winds from any other direction for that matter, in 1836 it was just not possible to know what the weather was already like a hundred to two hundred miles plus away from you. With a severe gale sweeping in with wind speeds gusting 50 knots or more, serious weather 100 to 200 miles away when you set off from St Peter Port would be with you in two to four hours which is less than the journey time between Guernsey and Weymouth. And so it was for the Flamer.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran