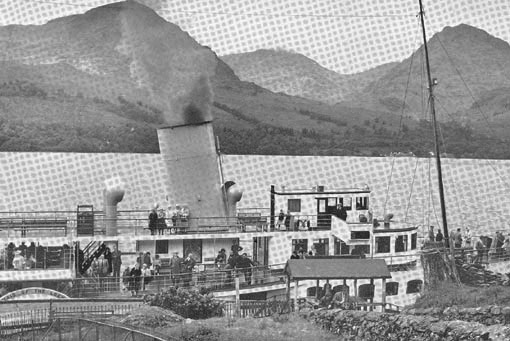

Built in 1953 by A & J Inglis for service on Loch Lomond, the beautiful paddle steamer Maid of the Loch (pictured top at Inversnaid) is fortunately still with us and, although minus her boiler and much of her outfit, is still in amazingly good structural condition.

Of all the laid up paddlers in the UK today surely this is the one which could most easily and most cost effectively be returned to service.

The Maid’s home pier at Balloch has lain at the end of a quiet road which almost nobody went down for many years so the ship was a bit invisible. Now all that has changed. The Maid and her pier are in full view of a massive tourism development which includes a large retail complex and aquarium on the shore of the loch. Things are looking up on Loch Lomond. And things are looking up for the Maid of the Loch.

The winch house, its steam engine and the slipway have been restored to working order to a very high standard and their opening last summer by HRH Princess Anne was a turning point in the Maid’s future. Now for the first time for more than twenty five years the ship can be hauled out of the water whenever necessary for survey and any underwater work.

Steel decks have been laid to make the ship watertight from the Scottish winter rain. The plan is for them to be clad with wood when funds permit.

The boiler was removed some years ago but the main engine and most of the machinery are all still in place.

The Maid never had a winch back aft and, like the Swiss steamers, used the power of the main engine translated through the ropes to bring herself alongside. One rope was put ashore from the promenade deck forward of the paddles and a second from aft leading ahead. When the slack was taken up on these by hand and the ropes made fast, the engines were turned slow astern and alongside came the Maid. For short calls the paddles were kept turning astern to hold the ship in place thereby obviating the need for anyone to go forward to put out a head rope which was generally used only when the ship was going to spend any time alongside a pier. I only sailed aboard the Maid once. That was around 1973 and I could hardly believe how easily the technique worked and how swiftly the ship came in and out of the piers. I was hugely impressed.

Ship handling of that standard requires a great rapport between the captain, engineer and rope handlers with each understanding what each other is trying to do and all working together as a team. It is a fine balance. The captain misjudging the wind, the engineer being too slow on the engine movements or, giving a different power to the engine than the captain expected or a rope handler missing a rope can all sabotage a good berthing and I understand that after Capt Nicolson retired some of the Maid’s attempts to come alongside were not always of the highest standard.

The Maid of the Loch ran with a huge crew of around thirty in her heyday making a ruinously high weekly wages bill for a ship which could carry a thousand but which more often sailed with less than three hundred. Fortunately smaller and more affordable core crews have now become the norm on passenger vessels and paddle steamers operating on the European lakes and rivers with jobs previously undertaken by two people often taken by just one and others done away with completely. For example, on almost all the European paddlers the master now does his (or her) own steering in and out of the piers from the bridge wing and greasers and firemen are a thing of the past. The Dresden paddlers have a core crew of just four, a captain, mate, engineer and one seaman and even the largest Swiss paddlers (La Suisse is 242ft long) a core crew of only six, a captain, mate, two engineers who look after the boiler and do their own oiling and greasing and two seamen one of whom doubles as the purser. Catering crew are added according to the likely needs of the number of passengers expected.

But for the Maid of the Loch an operating plan is all in the future. In the present, the team on Loch Lomond are to be heartily congratulated on what has been achieved so far. The ship is in good structural condition. The slipway has been restored. There is a revenue stream coming in from catering. It can surely only be a matter of time before a boiler is added and the ship fitted out enabling the paddles to turn once again.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran