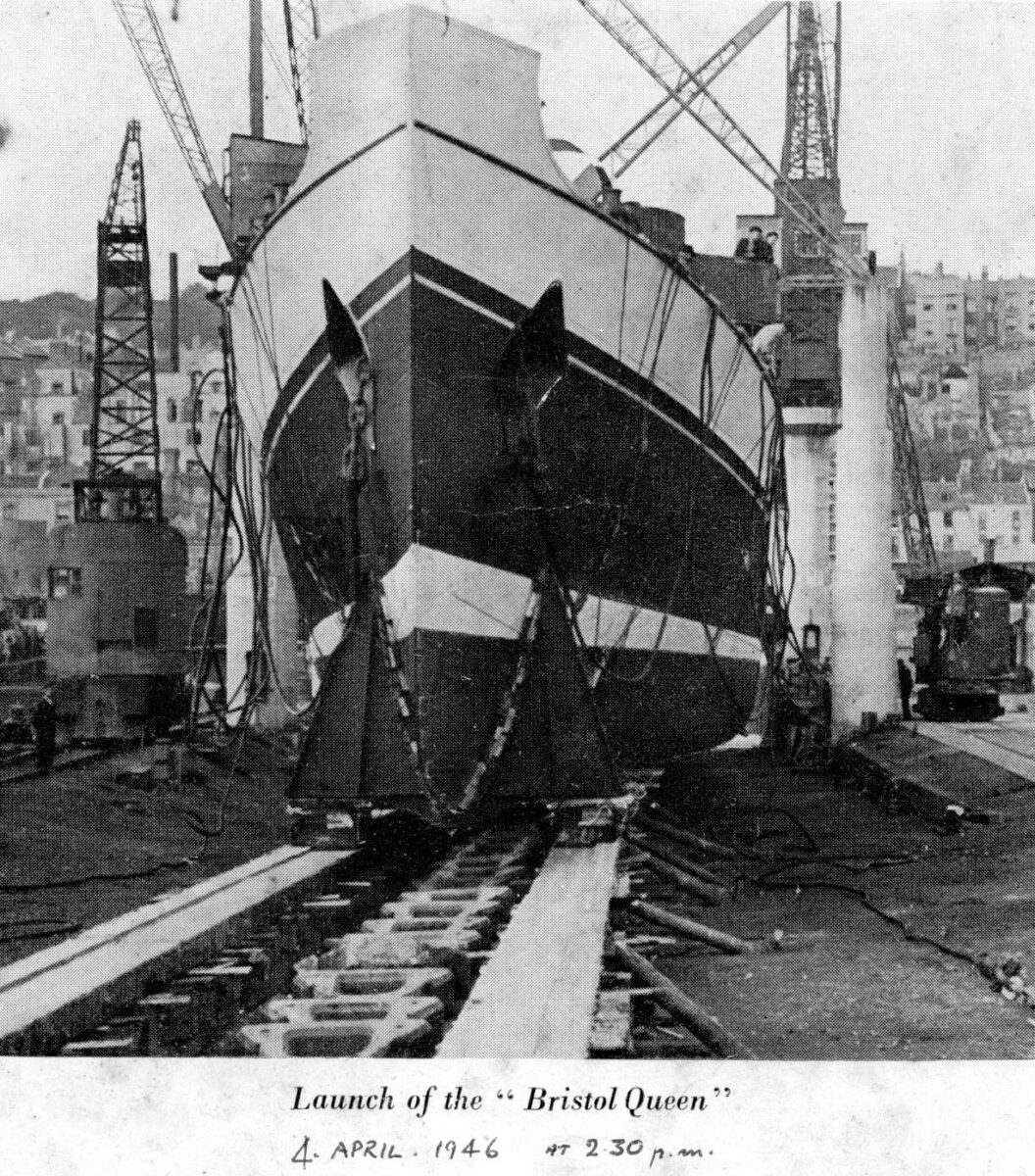

At 2.30pm on Thursday 4th April 1946 Bristol Queen was launched from the shipyard of Charles Hill & Sons by the Lady Mayoress of Bristol, Mrs James Owen, for P & A Campbell’s excursion services. Just a little short of 1,000GRT and 258ft in length overall, Bristol Queen was a big excursion paddle steamer specifically designed for the potential hurly burley of the Bristol Channel services.

A booklet of this great event was produced for the occasion a copy of which is now in the PSPS collection.

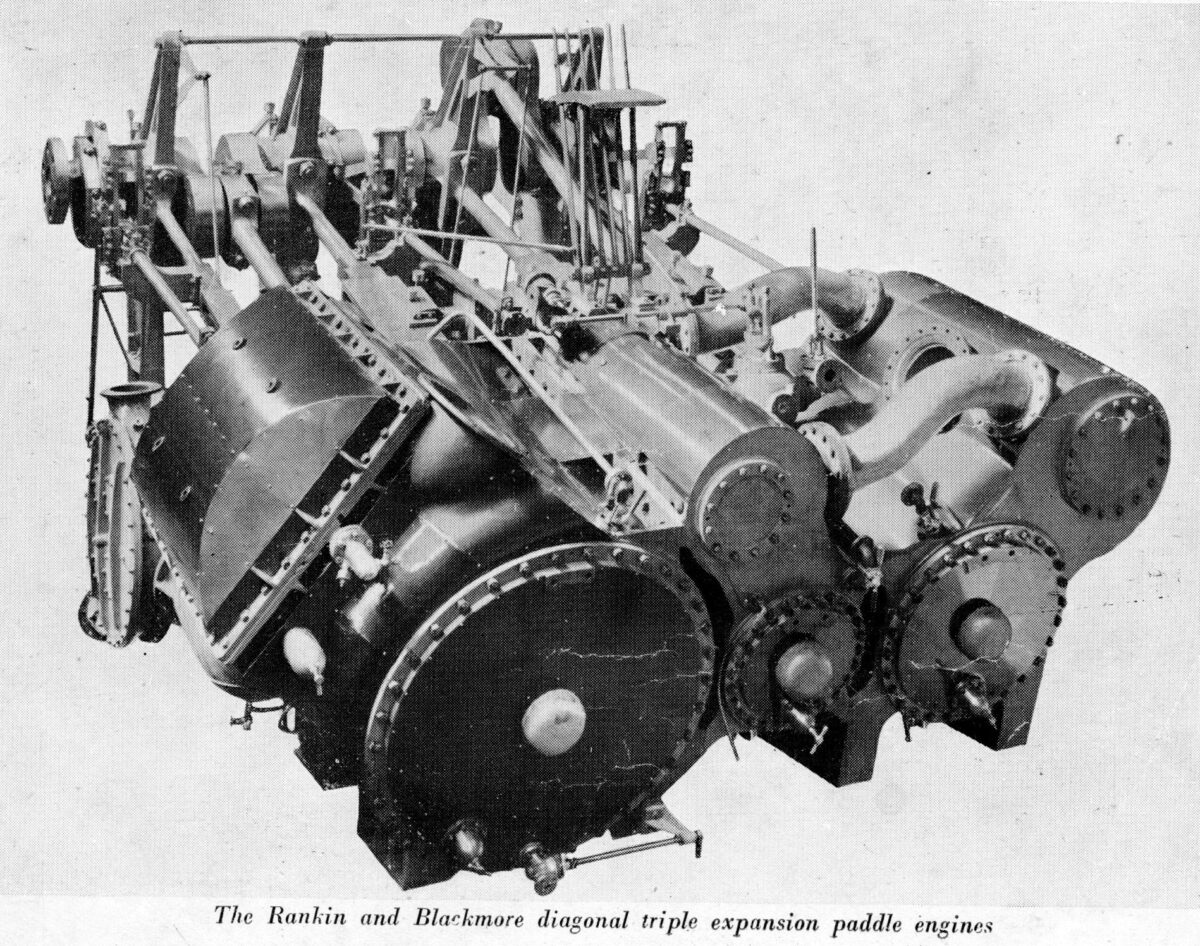

The engine was supplied by Rankin and Blackmore, the same manufacturer which the following year built the engine for our own Waverley. It was a triple expansion engine with the high pressure cylinder in the middle. the medium pressure cylinder on the right and the largest of them all, the low pressure cylinder, on the left. The engine was designed to push the ship along at an operating speed of 17knots when loaded and 18.5knots when light to cope with the tremendous Bristol Channel tides.

I think it is fascinating seeing how the peripheral kit was arranged in paddle steamer engine rooms. Here you can see the the circulating pump for sea water for cooling the used steam in the condenser was of the centrifugal variety and was sited midships on the port side. On KC it is at the forward end of the ER on the starboard side. On Bristol Queen there is a small steam driven 30KW electricity generating set positioned at the aft end of the ER on the port side close to the low pressure cylinder. And so on.

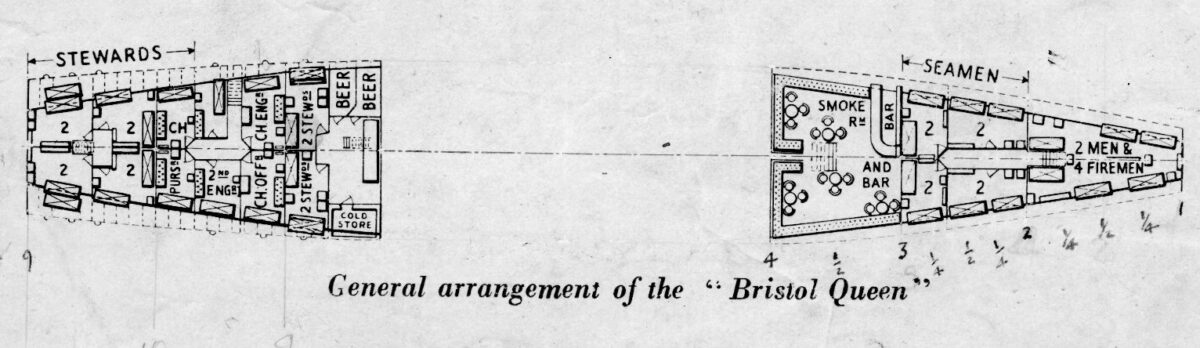

And then there is the arrangement of the accommodation on the ship. Of the 1,000 or so domestic passenger vessels currently in service around the UK the vast majority do not have the facility for crew to live aboard. Most crew on most domestic passenger vessels, even on large ferries like Red Funnel and Wightlink, are expected to go home at night and live within commutable distance of the ship. The same is true on most of the 50 or so paddle steamers currently operating in Europe. Of course there are exceptions to this but they are very much in the minority.

Providing crew accommodation takes up space on a ship and is an added operational cost. And if a ship starts and finishes its day at the same place why is it needed? Supplying what is in effect hotel accommodation for crews is not cheap including as it does providing bunks, mattresses, sheets, blankets, duvets, food and all the rest of it which all adds up the burden of costs and eats into the revenue.

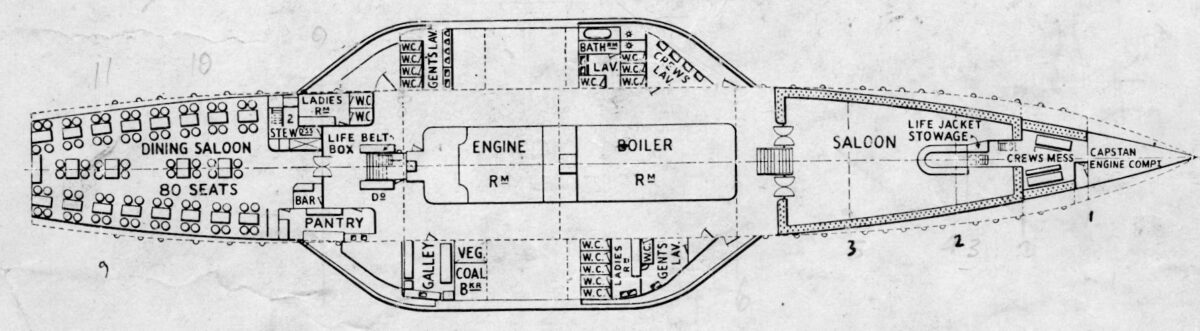

Bristol Queen had sufficient bunks to accommodate up to 35 crew living aboard. Up in the bow was space for 10 men and 4 fireman. On the main deck at the forward end of the aft saloon was a cabin for 2 stewardesses. At the aft end and forward end of the lower deck abaft the machinery was accommodation for 12 stewards. Between those sections was a space in the middle accessed from inside the aft saloon for individual cabins for the mate, chief engineer, second engineer and purser. The captain had a cabin in the accommodation block under the bridge which also housed the chart and radio rooms.

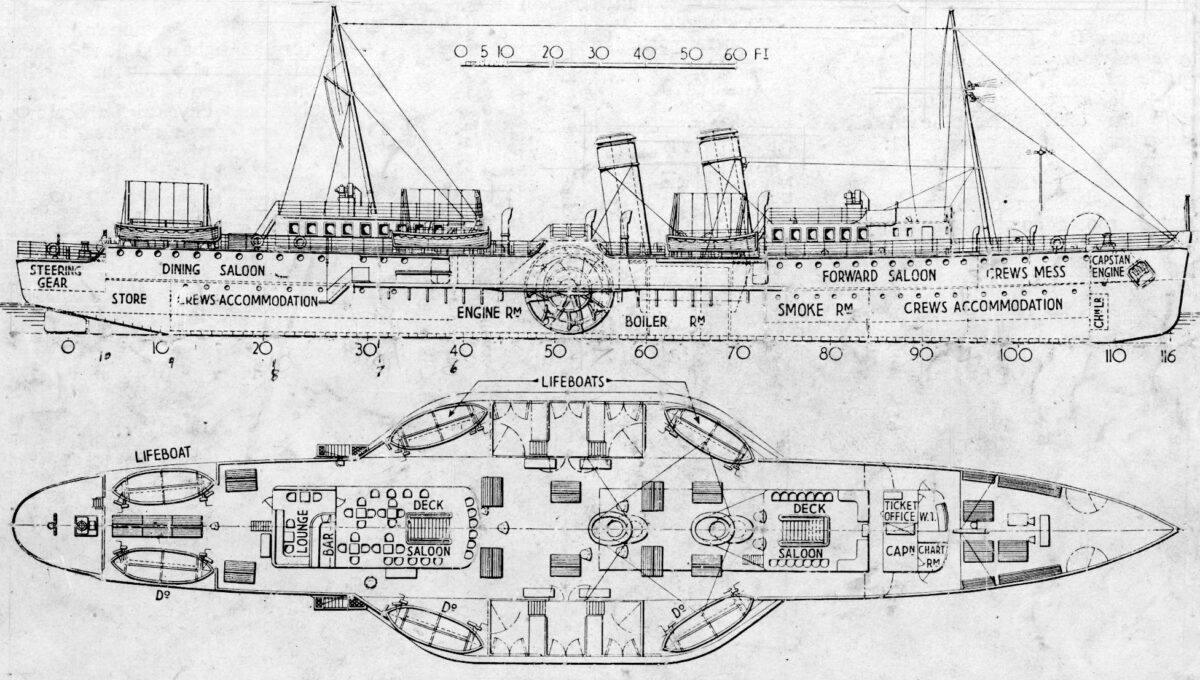

Bristol Queen was built to a standard to obtain a Class II Passenger Certificate for short international voyages for 836 passengers, a Class III for long coastal voyages up to 70 miles from the starting point and not more than 18 miles from the shore for 1,014 and a Class IV for “Partially Smooth Waters” (like the Bristol Channel in summer to the east of a line joining Barry Docks, Steep Holm and Brean Down) for 1,207.

Her dining saloon at the aft end of the main deck could accommodate just 80 seated at tables so even with two sittings for lunch and/or high tea there was a tremendous gap between the numbers potentially aboard wanting to be fed and the ability to feed them with a sit down meal.

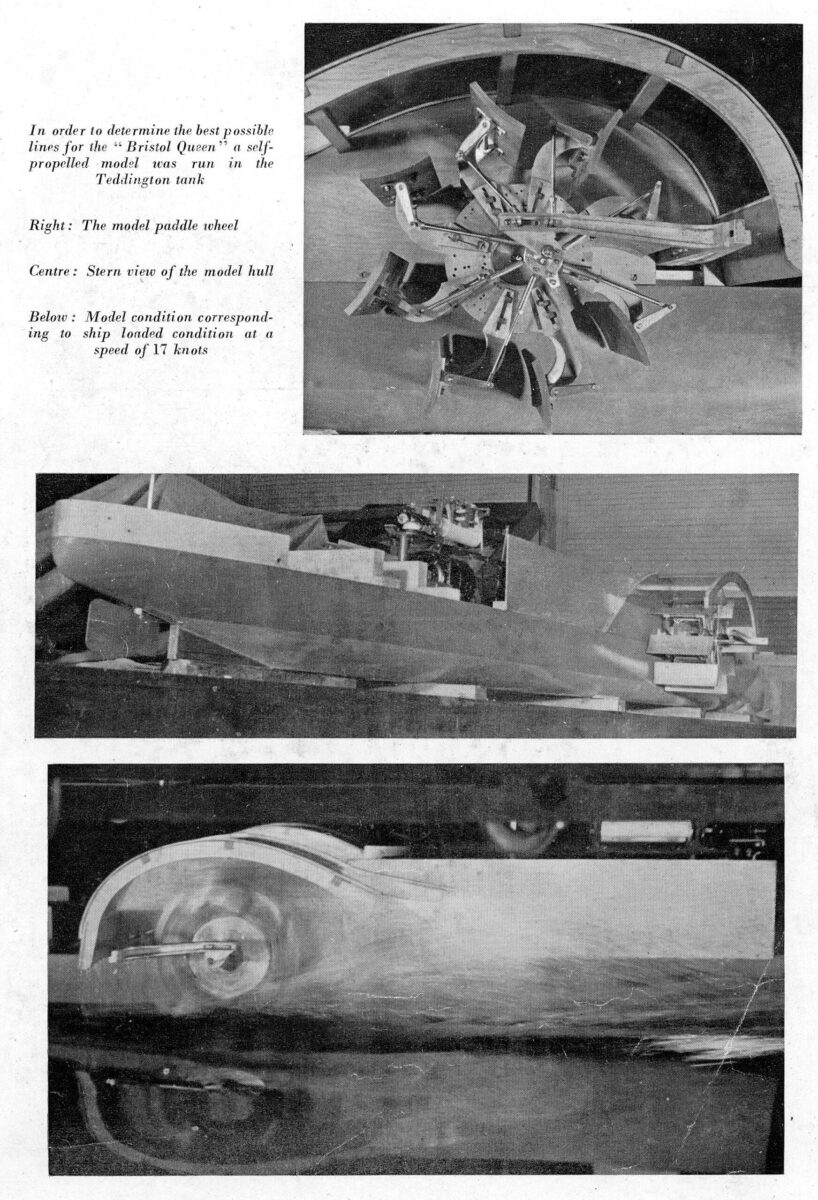

Of all the parts of the UK where excursion paddle steamers once operated the Bristol Channel provided some of the most challenging conditions with potentially big Atlantic swells to be coped with ever in the offing. This is why P & A Campbell eventually had portholes in the hulls of their paddle steamers at main deck level rather than panoramic windows found on paddle steamers elsewhere. Builder Charles Hill & Son were well aware of this and wanted to design a paddle steamer with stronger scantlings than many others and so had a model of her hull and paddle wheel design constructed and tested in the National Physical Laboratory at Teddington.

With work completed on fitting her out by early September, Bristol Queen set off down the Avon from Bristol for the first time on the afternoon of Saturday 7th September 1946 under the command of Capt J A Harris initially for compass adjustment off Avonmouth where she ended the day at half past six. The following morning she set off for trials around 11am but did not get very far calling for tug assistance within half an hour of departure to tow her back to Avonmouth. Whatever had gone wrong on the Sunday had been fixed by the Monday so she set off from Avonmouth under her own power for trials shortly after 10am completing a circuit of the Breaksea Light vessel off Barry before anchoring for a couple of hours in the afternoon off Walton Bay, Clevedon. She weighed anchor at 5.30pm for the run back up the Avon to Bristol where she arrived around 9pm. Her first public sailing was the following weekend with a run away from Bristol just after 9am down Channel to Ilfracombe on Saturday 14th September. She made her last trip of the season on Sunday 6th October.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran

This article was first published on 4th April 2021.