On Friday 20th August 1965 Princess Elizabeth left Weymouth at 9.30am for a day trip to Yarmouth, Isle of Wight with return at 7.30pm. It was a lovely day. The sun shone. There was not much wind. And there was a good load aboard.

I had got to know Captain Stanley Woods, her master that season, and he was most helpful and encouraging of the nautical ambitions of my then fourteen year old self. He was forever giving me nautical text books to study and then asking me probing questions from them later on. Going up to the bridge was a bit like entering an examination forum and I just lapped it all up as these were subjects which so interested me. I learned so much from him about seamanship, ship handling and navigation that summer for which I will for ever be grateful.

The Lizzie’s wheel was made of brass and was of of quite large diameter so that you had to stand on a raised plinth to reach over the top of it. Fortunately the wheel was saved by PSPS member number one, Mrs Eileen Pritchard, and is now in the PSPS collection store at Chatham.

There was not much kit in the Lizzie’s wheelhouse. She was not fitted with radar or an echo sounder. There was a medium frequency radio at the aft end but it was covered with a tarpaulin to shield it from leaks from the deck-head above. There was a fire extinguisher, a box for the binoculars, a signal flag locker and a table too small to accommodate a full chart. Unusually she didn’t have a voice pipe connection to the engine room but she did have an emergency engine signalling system for engine movements if the telegraph failed. This was a series of four buttons on a brass plate which you can see in the picture above just to the right of the radio. One button was for “stop”, a second for “ahead”, a third for “astern” and the fourth for “full”.

I never saw any of the captains on any of the bridges of any of the paddle steamers I sailed on in my youth ever fishing out a chart and working from that. They did carry charts, which were usually stowed in a rack under the deck-head, but they were sort of surplus to requirements as all the courses and distances between any two points anywhere and everywhere in their areas, plus all the other stuff you find on charts, was all memorised and in the captains’ heads.

They had to know everything in such very great detail to pass the Trinity House Pilotage examinations. In these the masters and mates were expected to describe in the examination, and without access to charts, everything which appeared on the charts. And if you take, say, the old Trinity House Isle of Wight district from the Needles up to Southampton, in and out of Cowes, over to Portsmouth and then out to the east through the Nab Channel, or the Thames from Tower Pier down to the NE Spit or up to Harwich then that is a tremendous quantity of marks, lights, leading lights, buoys and so on each with their individual flashes and other characteristics, some with sound signals as well. All had to be memorised plus the courses and distances between them all plus any other waypoints both sides of the channels inward and outward bound. Everything had to be learnt and for pilotage examinations still has to be memorised to this day.

Once this hurdle was over and their certificates had been granted, many masters and mates compiled their own course and distance books with all these details in them which they kept with them on the bridge and to which they could refer in case they ever had a slight memory loss in service. I compiled one of these for KC (and later for Waverley and Balmoral when I sailed on them) for the Medway and Thames and very reassuring it was to have in my pocket just in case of necessity.

On this day Friday 20trh August 1965 we set off from Weymouth at 9.30am on a course of 100 degrees for the 15 nautical mile run to St Albans Head (10.45am), then round onto 075 degrees for the 4 nautical miles to Anvil Point (11.05am), then onto 070 degrees for the 13.6 nautical miles to the SW Shingles Buoy (12.15pm) in the approaches to the Needles Channel.

From the SW Shingles to the Bridge Buoy off the Needles was 0.5 nautical miles on 050 degrees (12.18pm). From there to the Warden Buoy off Warden Point was 2.8 nautical miles also on 050 degrees (12.32pm). From there to a position 2 cables off Fort Albert was 1 nautical mile also on 050 degrees (12.37pm). From there to the Sconce Buoy was 0.7 nautical miles on 055 degrees (12.40pm). From there to Black Rock Buoy was 0.5 nautical miles on 085 degrees (12.43pm). And finally from there to Yarmouth Pier Head was 0.4 nautical miles on 100 degrees (12.45pm).

That’s a total distance between Weymouth and Yarmouth of almost 39 nautical miles. We left Weymouth at 9.30am and arrived off Yarmouth at 12.45pm three and a quarter hours later so we had been making 39/3.25 = 12 knots over the ground. The Lizzie had a speed through the water of about 11 knots so on this day our speed over the ground had been boosted by about 1 knot by having some tide with us.

The detail of what tides do is shown in almanacs and on Admiralty charts by tidal diamonds positioned at different locations on the chart and linked to a table showing the speed and direction of the tide at each of these tidal diamond points throughout the tidal cycle. So, for example, you can read off that four hours before high water at Portsmouth the tide is expected to be running at a speed of 2.5 knots in the direction of 082 degrees just off the Needles Approach Channel. And so on elsewhere and throughout the tidal cycle.

On this day the tide had been fairly helpful but it was not always so. On Wednesday 11th August we had not reached Yarmouth until 2pm. That meant that we had taken four and a half hours to cover the 39 nautical mile distance between Weymouth and Yarmouth so our speed over the ground that day had been knocked back by the tide to just 39/4.5 = 8.7 knots over the ground.

Arriving off Yarmouth we found the Embassy still alongside, where she was laying over on her day trip from Bournemouth. There was little sign of life aboard her so mate Arthur Drage tried calling her up on the radio but to this there was no response. Embassy’s radio was housed in the purser’s cabin on the port side under her bridge and nobody seemed to be at home.

Capt Woods gave a blast on the whistle. One or two heads appeared from below. There was a bit of scurrying about and one of the deck boys was seen running off from Embassy down the pier towards the town. Ten minutes later purser Frank Holloway and Chief Engineer Alf Pover were sighted hurrying back down the pier towards Embassy having had their shore based lunch interrupted.

Eventually Embassy moved off and we berthed port side to alongside the pier at 1.15pm and our passengers disembarked. We moved off at 2.30pm to free up the berth for Embassy to reclaim her load and returned at 3.15pm to load our passengers for a 3.45pm departure. We could have dropped the anchor whilst waiting but for the Lizzie that was quite a palaver involving lifting it over the bulwark in the bow using the anchor davit so we just drifted about in the Solent instead until it was time to come back in.

By now the tide was ebbing so we came off the pier astern and in the doing of it had a small argument with an inbound fuel barge which seemed determined to stand on. There was a little blowing of whistles as the barge motored on by and then we were off down the Needles Channel, across to Anvil Point, on to St Albans Head and then for Weymouth.

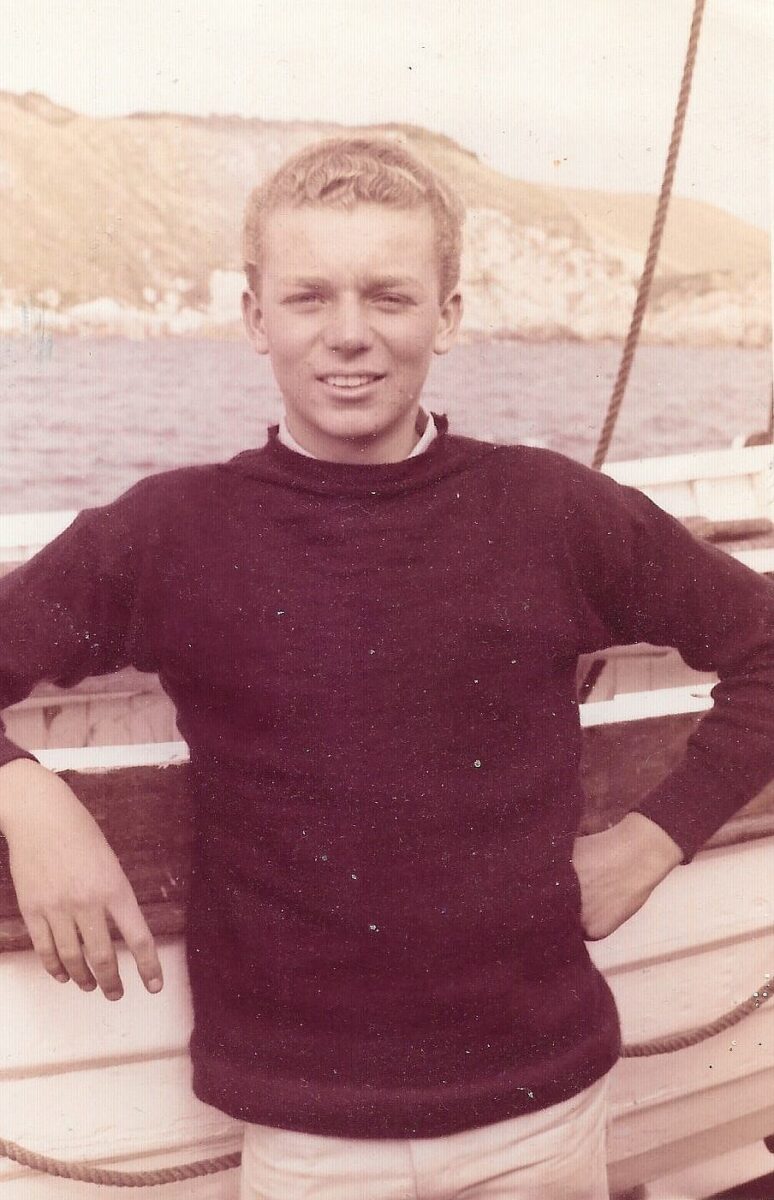

One of my schoolfriends Chris Miller was also aboard that day. He had been working as a summer job collecting the ticket money for the use of deck chairs on the Weymouth Pleasure Pier when one day the Lizzie found herself short handed. The Pier Master put him forward to fill the gap and so he became a seasonal deck hand polishing the Lizzie’s brass, handling the ropes and learning to steer. After school Chris went on to King’s College London University to read Physics and eventually became a Professor in Environmental Law at the University of Salford. We have remained in touch over the years and still meet up for lunch from time to time.

On arriving back at Weymouth Captain Woods was usually one of the first up the gangway making off for the railway station double quick to catch the train back to his home in Wilton Road, Southampton as he didn’t much like spending the night aboard the Lizzie if he could help it. The captain’s cabin, along with those for the mate, chief engineer and chief steward. were all under a fairly leaky deck head in the lower forward saloon which itself was a pretty airless space. I remember him saying that he found that sleeping aboard tended to give him a headache.

Captain Woods started his career on wooden sailing ships and had a master’s ticket in both steam and sail so had plenty of experience of rather less than comfortable crew quarters but he preferred comfort where possible. I recall his advice that if ever sleeping in such cabins it was important to leave your shoes the wrong way up before you turned in so that you would be sure that they weren’t filled up with water when you woke up.

However on this night he had to grin and bear it and stay aboard as the following morning bright and early a film crew was to use the Lizzie to play the role of a Cross Channel ferry for the big budget movie “Gordon of Khartoum” starring Charlton Heston. But that is a story for tomorrow.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran

This article was first published on 20th August 2020.