Sunday 18th January 1970 was Eppleton Hall’s first day out in the Pacific having cleared Balbao at the western end of the Panama Canal the previous day.

After two days spent in Cartagena in Columbia, Eppleton Hall was off again on the 275 nautical mile run across to the entrance to the Panama Canal. Captain Scott Newhall recorded that during this passage the tug was off some of the rockiest and trickiest coastline of the entire voyage with its mass of coral islets that is well known to mariners for its contrary minded, unpredictable and often very strong currents that appear to run in every conceivable direction. As they left the barometer started to fall and continued to do so over the next couple of days making the passage uncomfortable.

Two days on mountain tops were spotted on the horizon. They stayed in the same position but growing larger all the time indicating that Eppleton Hall was being set towards the shore by a strong current. The Fathometer dropped from 150 fathoms to just 35 fathoms and kept falling. There was also a worrying lack of other ships in the vicinity making for, or proceeding from, the Panama Canal. So the captain turned the tug seawards once again aiming for deeper water as he was just not sure exactly where he was, A prudent move in the circumstances in my view.

The weather deteriorated but eventually other ships bound for the canal were sighted and Eppleton Hall followed them and entered the canal anchorage on the evening of 14th January 1970 without picking up the lights on either sides of its entrance..

The following morning the pilot came aboard and reported that they had just missed the centre of the worst storm in Panama since 1943. It had been so ferocious that it had demolished part of the breakwater taking one of the entrance lights with it after which a large freighter hit the light on the other side taking that one out too. So they hadn’t missed seeing the lights. They just weren’t there.

Eppleton Hall was made fast to the large mechanical towing mules either side in the first lock sharing water with the Japanese cargo ship Shoyomaru. The lock filled up and Eppleton Hall ascended the water-filled staircase proceeding from lock to lock towed always by the mules.

About one hour later she was in the canal itself in which she was confronted by another real hazard, a tremendous quantity of flotsam, including tree stumps, logs and heavy clumps of vines and water-lilies, which had been washed down from the Chargres River in the storm.

The young and conscientious pilot had been anxious about this debris damaging the paddle wheels so had organised a tug with two barges to proceed ahead of Eppleton Hall to try to clear the debris out of her way. Get out your magnifying glass and you will see her just to the left of the captain’s nose in the picture above.

Officialdom took a very favourable and positive view of this unusual vessel passing through their carefully regulated system and offered every assistance. On the day she left Balbao, at the western end of the canal, a group of the tug’s new friends from the Panama Canal Company came aboard for the ride out to the pilot boat at the entrance channel. The weather was lazy and hot and the Gulf was absolutely flat calm and shimmering under the bright sun as Eppleton Hall flapped off in a southerly direction making for the next headland at Punta Mala on the south eastern tip of Panama.

Since starting her voyage in Newcastle upon Tyne way back in September 1969, Eppleton Hall had steamed around 6,000 nautical miles so far. Only another 3,246 nautical miles to go then up the coasts of Costa Rica, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico and the USA before reaching her final destination in the San Francisco Maritime Museum where Eppleton Hall’s mate Karl Kortum was Museum Director. In his other life her master Scott Newhall was Editor of the San Francisco Chronicle. Both were highly experienced yachtsmen with a life time of being afloat including crossing oceans. And both agreed at the outset that this was a voyage which they wanted to undertake without any large ship deep sea certificates of competency aboard.

To be continued.

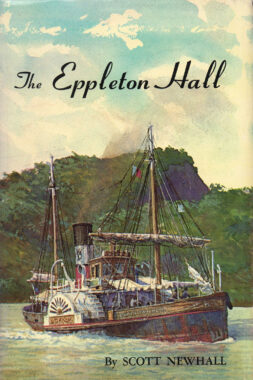

For the full story of this epic voyage from Newcastle to San Francisco try to get hold of the account by her master, Captain Scott Newhall, called “The Eppleton Hall” and published in 1971 by Howell North books in Berkeley California, ISBN 978-0831070854.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran

This article was first published on 18th January 2021.