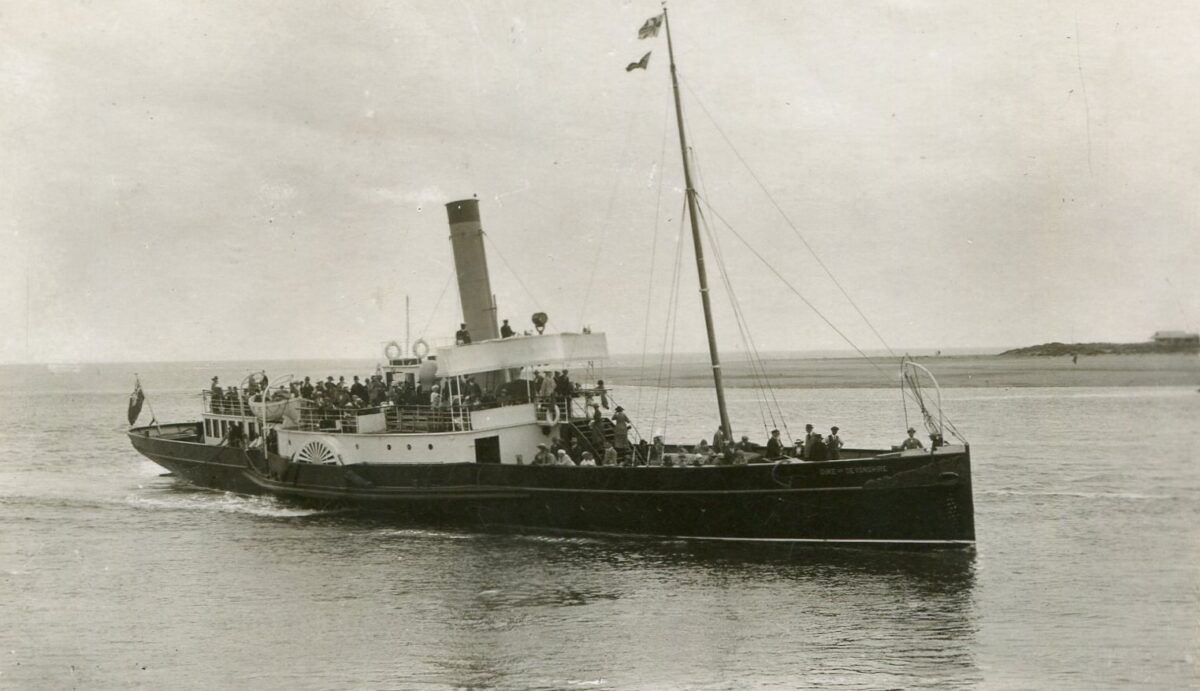

On 10th December 1937 Cosens signed the Bill of Sale to buy the Duke of Devonshire from her then owner, Mr Alexander Taylor of Torquay.

Built in 1896 the Duke, along with her almost identical sister Duchess of Devonshire, had been a mainstay of excursions along the Devon and Dorset coasts from Exmouth and Torquay up to the 1930s. By then that trade was in decline with the consequences of the 1930’s depression producing a diminished market coupled with competition from smaller and more economical motor launches as well as from the paddle steamers of Cosens in the 1920s and P & A Campbell in the early 1930s.

Bought by Campbells in 1933 to get her out of the way and leave the way open for their own Westward Ho!, they then sold the Duke on for further service at Cork in Ireland. That lasted a couple of years after which she was bought by Mr Taylor who planned to bring her back to revive her old trips from Torquay in 1936.

With a boat built for the job, in a market by then devoid of comparable competition and reviving old trips which no paddle steamer had operated in 1935, Mr Taylor must have thought that he was on to a winner in buying the Duke. How could it not work out well? But running a paddle steamer, particularly an elderly one in need of major investment in her fabric and structure, is easier said than done and after two seasons he had had enough and the Duke was back on the market.

But in 1937 who would buy her? She wasn’t fast enough for, and was not fitted out to the standards expected by passengers for, the Bristol Channel or the Thames. The Clyde was in the hands of the rich railway companies. The south coast from Seaton to Dover was dominated by (west to east) Cosens, Red Funnel, the Southern Railway and Campbells. Perhaps the north Wales coast might suit but now there was new modern tonnage there with which to compete. Maybe the north east like Scarborough or Bridlington. They had taken an old Cosens paddle steamer and renamed her Bilsdale but even she had finished now and been replaced by more economical Diesel tonnage. Then there was the scrapyard. That was surely the most likely outcome.

There was one last option. Maybe, just maybe, the Duke could be offloaded onto an existing paddle steamer operator. Perhaps there was a company out there which needed a smallish paddle steamer which could go to sea, put her bow onto the beaches to load and unload passengers and, due to her modest size, was comparatively cheap to operate.

And so it turned out. Cosens bought her as a replacement for their antique Premier. The Duke ticked a lot of boxes for this Weymouth based company from an operational point of view and most particularly she was cheap. That’s a thing Cosens always liked. Mr Taylor had initially hoped to get up to £2,500 (which scales up to about £168K in today’s money) for her. In the end Cosens bought her for just £1,000 (or about £68K in today’s money). That’s not a lot is it? That’s cheap. That’s scrap value.

However if you are buying an elderly paddle steamer you may be buying an asset but you are also buying a liability. Ships are built to last about twenty five years top whack. After that they either need scrapping or major investment in renewal of their basic structure. In 1937 the Duke was already more than forty years old and although money had been spent on her after the First World War (in which she sailed as far as the Dardanelles) that was approaching twenty years before. Cosens knew all this. But they also knew that they had their own works, their own slipway and their own workforce so all but exceptional work could be done in house and therefore on a much more cost effective basis than if they had had to contract out to independent yards. They were also aware that although the Duke may have been, and was, over forty years old, she was a spring chicken compared with the Premier they were replacing which by 1937 had clocked up a staggering 91 years of service.

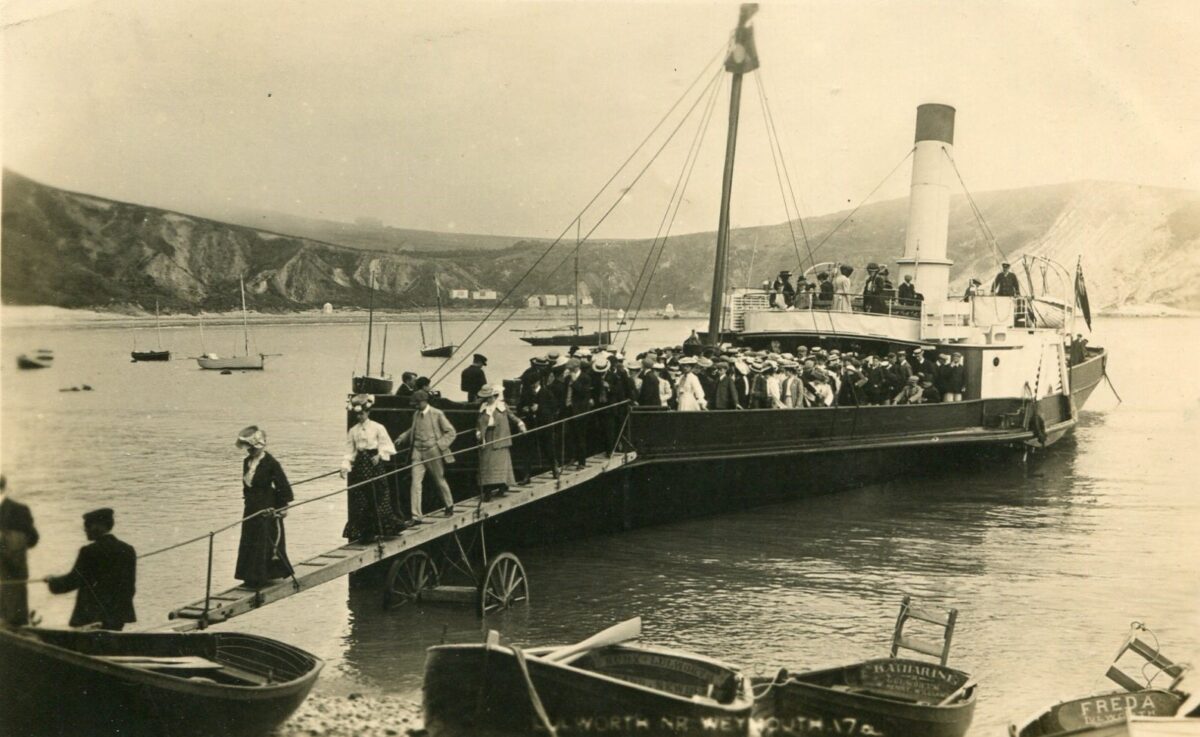

In April 1938 Cosens steamed the Duke from Dartmouth to Weymouth where she was given a major refit which included a replacement, and more modern, funnel as well as much else. Renamed Consul, she was then based at Weymouth for most of her twenty five year career as a Cosens paddle steamer sailing on local trips as well as to Lulworth Cove, Swanage, Bournemouth and Totland Bay on the Isle of Wight and so on. In September 1960, (and again in 1961) Consul was chartered for an evening cruise by the PSPS.

By 1961 the Board of Trade was expressing serious doubts about Consul’s structure which resulted in her sailings being restricted to an area bounded by Lulworth Cove and Portland Bill in 1962. After that, and with major work being required in the offing, Cosens got rid of her and by the spring of 1963 she had passed into the ownership of a new company, called South Coast and Continental Steamers Ltd, fronted by Tony McGinnity, one the founding fathers of the PSPS. Like Mr Taylor, nearly three decades earlier, Tony managed to get just two seasons out of her before expenditure exceeded income and the game was up.

In 1965 Consul became a static accommodation ship for a sailing academy at Dartmouth. In the spring of 1969 she was scrapped in Southampton over thirty-two years after Cosens had bought this by then already elderly vessel on 10th December 1937.

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran

This article was first published on 10th December 2020.