In 1930 the Southern Railway commissioned two very large paddle steamers, Whippingham and Southsea, for their Portsmouth based services.

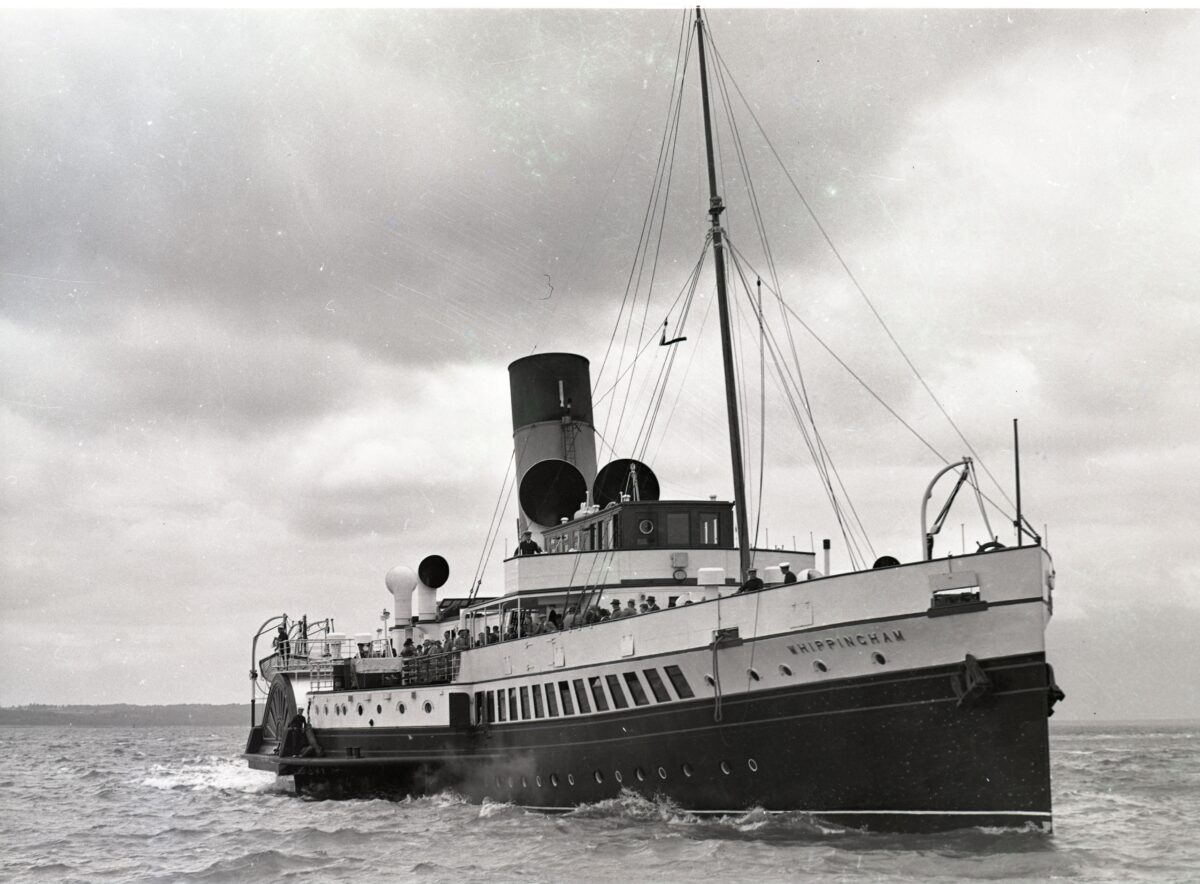

At 244ft LOA and 825 GRT they were a huge step up from Portsdown built a couple of years earlier which was only 190ft LOA, 342 GRT and of broadly similar size and design to the rest of the fleet.

Whippingham and Southsea were intended to increase capacity on the Portsmouth/Ryde ferry service particularly at peak times; to offer the seasonal direct services from Portsmouth and Southsea to Sandown, Shanklin and Ventnor; for excursions within the Solent particularly to view the liners sailing in and out from, and berthed in, Southampton and for some longer excursions to more distant destinations including sailing round the Isle of Wight.

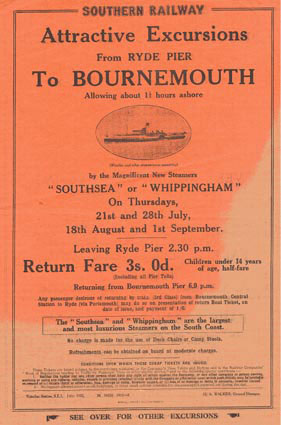

I have some of the steamer notices for 1932 with me here and I see from them that one or other of the two was advertised to sail on Wednesdays from 20th July to 21st September from Portsmouth (2pm) Clarence Pier Southsea (2.15pm) and South Parade Pier Southsea (2.30pm) to Bournemouth for an hour and a half ashore and on Thursdays 21st and 28th July, 18th August and 1st September half an hour earlier to Bournemouth also picking up at Ryde (2.30pm)

Bournemouth Pier was also served by the paddle steamers of Cosens and what became Red Funnel so could sometimes be quite busy. There were two berths on each side which could accommodate four paddle steamers in total at any one time.

I have a copy of the Byelaws to Regulate the Use of Bournemouth and Boscombe Piers which state at section 11: “No vessel other than a passenger vessel of a gross tonnage not exceeding 800 tons or with a draught of not more than 7ft shall traffic at the Pier or under any pretence whatever touch at the Pier except with the permission of the Pier Master.”

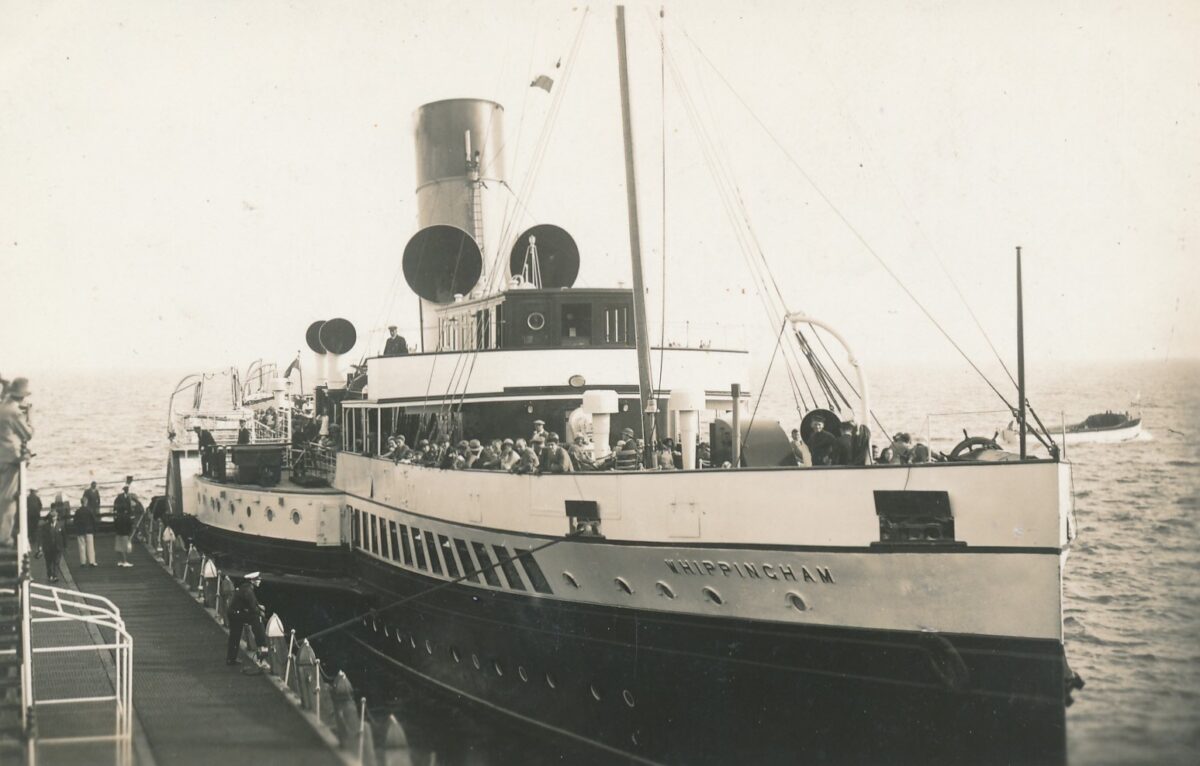

Whippingham was 825GRT, 25GRT above that limit and so would have needed that special permission from the Pier Master which we must presume was granted as she did call at the pier. Doubtless the County Borough of Bournemouth, as then constituted, would have wished to have a good working relationship with the Southern Railway which provided the main rail services in and out of the town. Maybe a condition of this special permission was that when Whippingham and Southsea called they would berth only with their sponson right at the end of the pier, as in this pic, so that if they caused any damage that would be limited to only a tiny portion of the landing stage right at the end and therefore not cause inconvenience to the other operators.

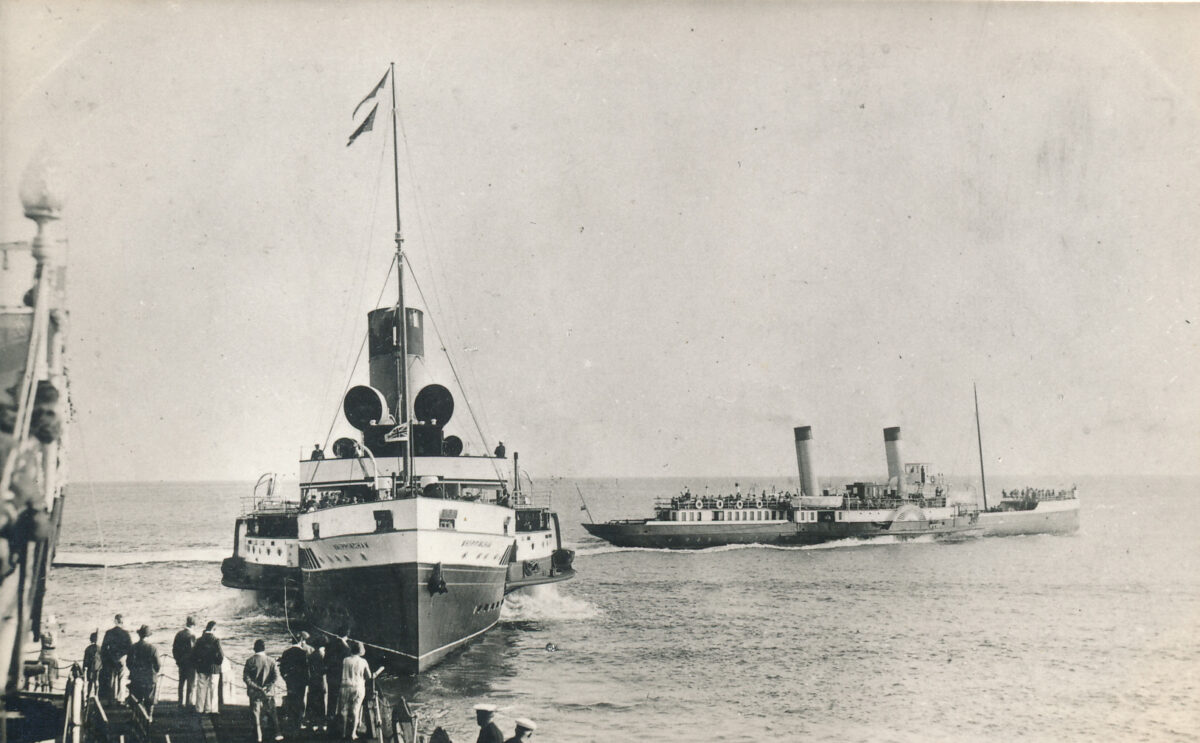

There were sometimes other difficulties too. Take this pic. Ignore the white wash coming out of Whippingham’s paddle wheels for a minute. We will come back to that. Instead look at the water between her bow and the pier. It is clear from this that she has been going gently astern from the pier leaving this modest wash. But she could not carry on astern because Monarch was in the way crossing astern of her. You can imagine Whippingham’s captain’s heart sinking after he had let go aft, let go the spring, rung full astern, started to back out and then, as he came clear of the pier, saw Monarch right in his way. Oh dear. He knew he could not stop before the bow had cleared the pier. Look at the position of Whippingham. She is being pushed in an easterly direction (right to left in this pic) by the tide. If he had stopped before the bow had cleared the pier then the forward part of the hull would have been set onto it by the tide and made contact which might have caused damage. So he had to keep going astern until the bow had cleared the pier before stopping to wait until Monarch had past astern of him continuing all the time to be set sideways in an easterly direction by the tide. By the time this pic was taken Monarch was clear so the captain has rung down full astern as you can see from the strong white wash now coming from the paddle wheels and so off she went.

Whippingham’s departure time from Bournemouth was 6pm so Monarch would have been setting off for her last trip of the day to Swanage in this pic.

Clear of the pier and Monarch, Whippingham is now away from Bournemouth on her way back to Portsmouth. In the foreground is one of Jake Bolson’s Skylark motor launches which ran trips from a pitch on the Bournemouth Beach including “Around the Dorset Lakes” of Poole Harbour.

In this pic look at the aft end of the funnel. There are two waste steam pipes going up the back of it one for each of the boiler safety valves plus a U shaped overflow pipe on the right. Before this time whilst any one boiler required two safety valves the waste steam was permitted to go to atmosphere up just one connecting pipe for smaller ships. For those vessels of the size of Whippingham they now needed a separate pipe for each safety valve hence the two pipes. These exhaust pipes were always made of copper. Steel was not permitted as it would inevitably corrode in due course sending small flecks of rust down the pipes which might get stuck in the safety valves potentially impeding their necessary function.

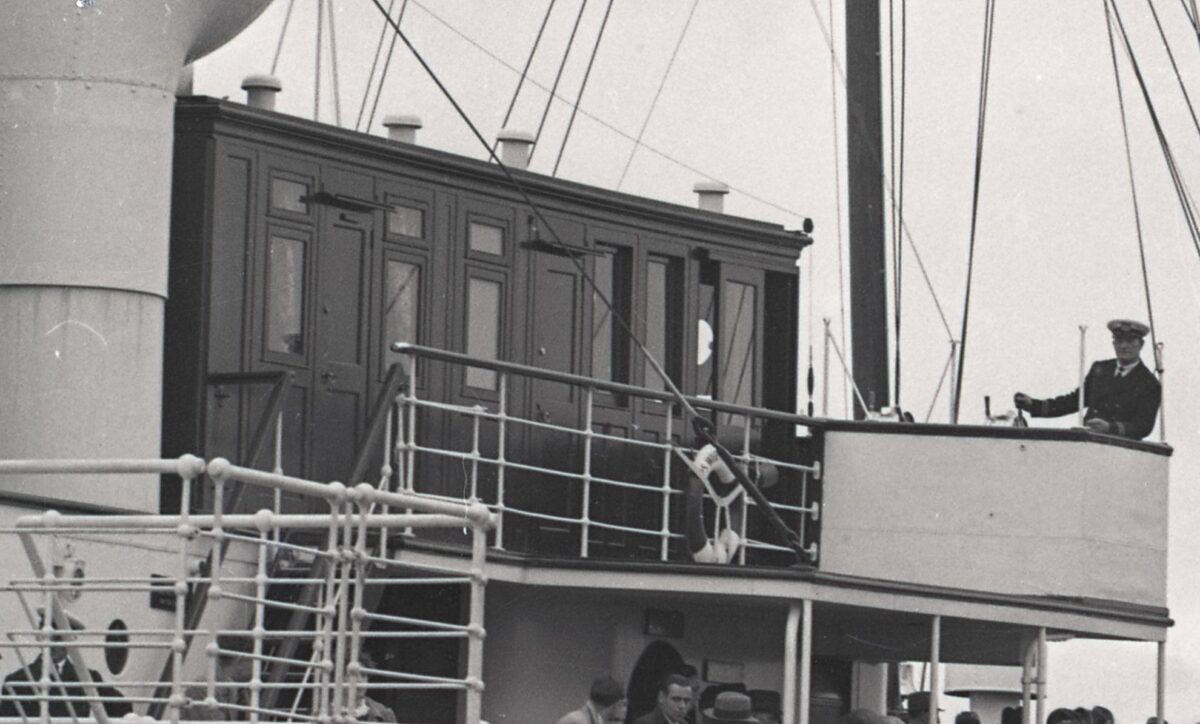

Take a closer look at Whippingham’s bridge. As you can see abaft the wheelhouse there are two doors to small private cabins which could be hired at a premium fare for those passengers wanting to buy a little bit of extra peace, quiet and anonymity. Maybe the Lord Lieutenant travelling to and from the Isle of Wight. Maybe Harry Lester, star of the seaside show at Sandown that summer. Maybe your granny or mine feeling a little flush and trying to get away from the overwhelming pressures and noise of the crowds.

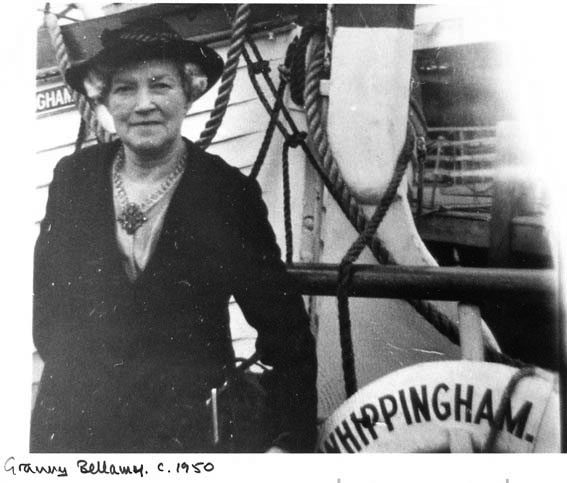

And speaking of grannies here is Capt Mike Ledger’s Granny Bellamy pictured aboard Whippingham in 1950.

Southsea hit a mine and sank off the Tyne on 16th February 1941 whilst on military service as a minesweeper. After service also as a minesweeper Whippingham returned to Portsmouth and resumed her ferry work but not her longer distance excursion programme. As the years rolled on it became clear that the railway spent as little as they reasonably could on her annual maintenance to keep her annual operating costs down. In this pic from 1962, her last season in service, you can see that the lovely varnish of the bridge woodwork has been replaced by white paint.

There was a lot of that going on in the 1960s as paddle steamers came to the end of their operational careers. I remember Princess Elizabeth having the lovely wooden varnished tops to her rails smothered in brown paint. Consul had her wheelhouse painted white and at one stage parts of her magnificent domed forward saloon skylight daubed with pea-green eau-de-nil paint.

Varnishing is a labour intensive task. To get the full effect you need multiple coats plus multiple sandings between each application. With paint you can get away with slapping it on and it will easily last the season and look sort of OK particularly if you didn’t know that it had replaced varnish.

After Whippingham’s last summer season in 1962 she was laid up at Portsmouth alongside HMS Kenya. She was towed away from Portsmouth on 17th May 1963 bound for the breaker’s yard in Ghent.

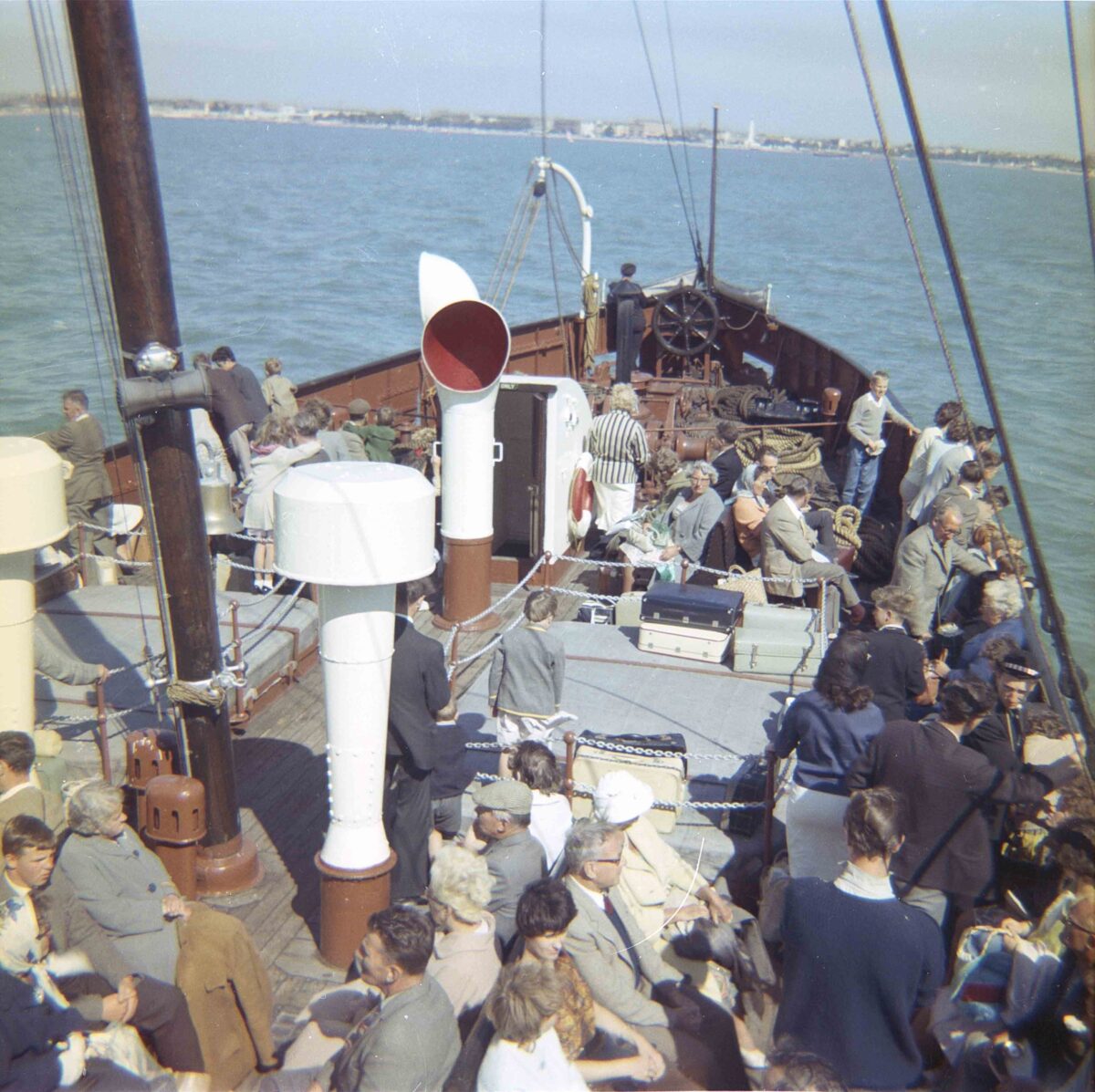

Tiny Point of Detail 1:

Like all the other Portsmouth based paddle steamers Whippingham had a bow rudder for working astern. You can see the wheel for it up in the bow. In these long gone days which predate the universal use of hand held radios, communication between the bridge and the man on the wheel in the bow was by hand signals. The seaman standing next to the bow rudder wheel in this pic is the lookout. It was the policy for all the Portsmouth based paddle steamers to have a lookout positioned in the bow at all times when sailing within the Solent and Southampton Water.

You can also see Whippingham’s two traditional cargo hatches with their blue tarpaulin covers over their wooden hatch boards. Goods were lifted aboard by cranes at Portsmouth and Ryde and kept dry in the holds. There are so many ways of skinning cats. The Portsmouth paddle steamers had these special cargo holds. On the Clyde such cargo, including vehicles, as was carried by the paddle steamers there was loaded aboard amidships over planks and stowed on deck out in the open around the funnels.

Note also the combination of mushroom ventilators through which air for ventilation below deck was mechanically drawn and traditional free flow ventilators.

Here is Whippingham backing away from the Harbour Station at Portsmouth. Sometimes the paddle steamers turned in the harbour using a combination of both the bow and stern rudders. Sometimes they backed out through the harbour entrance using the bow rudder and steamed all the way down to Clarence Pier before turning.

Tiny Point of Detail 2:

Whippingham’s only sailings in 1962 were on just eight Saturdays between 14th July and 1st September on a roster which included departures from Portsmouth at 10.45am, 12.45pm, 2.45pm and sometimes at 4.45pm with the corresponding returns from Ryde. This was the last summer where her huge capacity was needed to help shift the crowds on change-over Saturdays as people flocked to and from the Isle of Wight for their summer holidays. The world was changing. The cry was starting to go up: “Next year let’s book a week in Torremolinos where the sun always shines instead of Shanklin where it might rain and we will have to spend our precious holiday week huddled up in shelters on the promenade.”

Tiny Point of Detail 3:

Capt Brian Wright was master of Whippingham as well as other vessels in the fleet in 1962. He went on to become Marine Superintendent of Sealink at Portsmouth and in 1983 sailed with Waverley on her visit to the Solent offering his local knowledge and paddle steamer expertise to a young Capt Steve Michel that season making his South Coast debut as Waverley’s master.

Tiny Point of Detail 4: To get a feel for the difference in scale between Whippingham, Southsea and the other paddle steamers in Southern Railway Portsmouth based fleet in 1930 count the number of portholes in the sponson housings forward of the paddle box:

Shanklin had four.

Whippingham had eight. Wow! They were big paddle steamers.

Pictures from the collections of PSPS, Keith Abraham, Tony Horn and JHM

Kingswear Castle returned to service in 2023 after the first part of a major rebuild which is designed to set her up for the next 25 years running on the River Dart. The Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle Trust is now fund raising for the second phase of the rebuild. You can read more about the rebuilds and how you can help if you can here.

John Megoran